The following, from Aidan Nichols’ Chalice of God, is a beautifully concise summation of the some of the main fruits of 20th century Trinitarian thought:

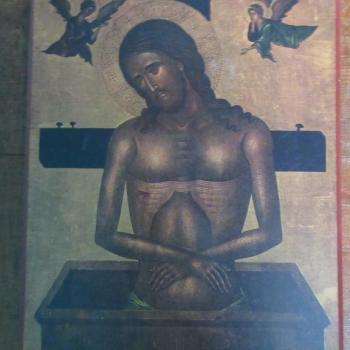

As “expositionally taught,” the revelation of the Trinity turns crucially on the doctrine of Jesus himself–for which I accept as witness the historical value of the Fourth Gospel…as the work of an eyewitness of the Word “in whom are hid all the riches of wisdom and knowledge” ( Col 2:3). But the teaching is marvelously confirmed by the Paschal Mystery, where is is not expounded but enacted. I accept with St. Thomas that Christ “carried his cross as a teacher his candelabrum, as a support of the light of his teaching, because for believers the message of the cross is the power of God.” By coming in Christ in his own person to a lost world, the eternal God made known in painful yet efficacious act, and not only in teaching, both himself and his love for the fallen creation. The triune relationality occurs in the history of Jesus, without its being in any way the case that the economy retroactively reshapes the self-relatedness of the divine Persons. I reject the interpretation of Trinitarian narration read sequentially, as though the flow of relation corresponded to a temporally developing relationality within the triune God. It is enough to say of the Christ of Good Friday and Easter, with Mother Julian of Norwich, “Where Jesus appears, the Blessed Trinity is understood.”

I ask, however, How should we understand the ontology of the act of the divine being, in the light of which the narrative can be rendered coherently as an account of the character of the divine life? In the light of the narrative of the divine self-involvement that climaxes in the Paschal Mystery, there is egregious confirmation of what I have inferred from the “expositionally taught”: divine being is through and through the being of love. In the exercise of divine nature by the Three, we are further instructed on that love’s hypostatically characteristic mode.

Specifically, the love shown in the Paschal Mystery is kenotic–self-emptying–or sacrificial love.. With Sergei Bulgakov and Balthasar, though deploring their rhetorical excesses, I affirm that the Paschal Mystery reveals by analogy the eternal, mutual kenosis of Father and Son in the ecstasy of love that is the Holy Spirit, for the Father and Spirit differ from the Son only in their “relations of opposition” (respectively, fatherhood and procession, rather than generation) and in naught else. Each such relation involves a sacrifice, a “kenosis,” an act of self-humiliation.Thus, as to the Father, From all eternity the Father possesses his divine nature only as giving it to the Son. Such fatherhood, writes Bulgakov, is the very image of love, since “He who loves wants to possess himself not in himself but outside himself, so as to give his ‘I’ to this other ‘I’ in such a way that he is identified with him; [he wants] to manifest his ‘I’ by a spiritual birth, in the Son who is the living image of the Father.” So the Father’s begetting of the Son is the primal act of possessing the divine nature where the Father has his nature passing it on, through giving it away.

As to the Son: Just as the Father wants to possess himself only in the Son, so the Son does not want to possess the divine nature for himself. He wants rather to offer his personal selfhood, his seitas, in sacrifice to the Father. He is the Word, yes. But this means he is the Father’s Word,not his own. When the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son (or, as the Middle Byzantine theologians would say, by “resting on” the Son), a triumphant testimony is given to the sacrificial exchange which joins the Father and Son forevermore. For this sacrificial exchange is what produces the Holy Spirit.

As to the Spirit: In the Trinity the Spirit exists by showing the Son to the Father and the Father to the Son. He is the moment of their mutual love. The Holy Spirit possesses the divine nature as the joy of sacrificial love. He is God as the beatitude of the love of Father and Son, its perfect fruit. Thus for Balthasar, since each of the hypostases is identical with the divine essence, the whole divine nature is congruent with self-gift. Though the essence is indivisibly one, whilst the Persons are three in number, the former must be such as to account for fitting possession by the latter ( a key assertion of Bulgakov’s sophiology too. This would justify theologically, in its Source and Trinitarian manner, the claim that self-giving love is the primordial, transcendental characteristic of being, which Balthasar’s friend Gustav Siewerth asserted when speaking philosophically of the world, of what is involved in bestowal on recipients of the actus essendi.

In the light of Pentecost, we can say of the Holy Spirit that it is he who enables the world to be in Christ and Christ to be in the world. For this reason he is the Spirit of the Church, since the “renovated creation” in Christ is an “ecclesialised cosmos”. The communion of the faithful in the Church flows from the Trinitarian communion; what St. Cyprian had seen of the Trinitarian matrix of the Church, St. Augustine expresses in terms of the Spirit as the consubstantial Charity of the Father and Son. “The society of the unity of the Church of God, outside of which there is no remission of sins, is at it were the proper work of the Holy Spirit, with whom the Father and Son cooperate, because the Holy Spirit is in some manner their fellowship.” With this I compare the words of the American Dominican Romanus Cessario: “He who in the depths of the divine reality is the perfect image expressed by the Father and who together with the Father breathes forth personal love as the bond of friendship, replicates this divine communion within the medium of his humanity and his human history for our sakes.”

Aidan Nichols. Chalice of God: A Systematic Theology in Outline. Liturgical Press, 2012.