1. The Church has no expertise in economics, which is a technical area best left to experts.

In fact, Church teaching on economics, and Catholic social teaching in general, is firmly rooted in moral theology. As Pius XI put it in Quadragesimo Anno, it is “an error to say that the economic and moral orders are so distinct from each other that the former depends in no way on the latter”. That error is rather common in today.

John Paul II is equally clear. In Centesimus Annus, he notes that “social doctrine, by its concern for man and by its interest in him and in the way he conducts himself in the world belongs to the field of theology and particularly of moral theology”. In Sollicitudo Rei Socialis he says that social teaching is part of the doctrinal corpus, and that “with the development of peoples”, the Church “cannot be accused of going outside her own specific field of competence and, still less, outside the mandate received from the Lord”. The Church, after all, is an “expert in humanity”.

2. We should emphasize private charity over state action.

Catholic social teaching is quite clear on the two pillars of charity – the private path and the institutional path. As Benedict XVI says explicitly in Caritas in Veritate, the institutional path of charity is “no less effective than the kind of charity which encounters the neighbor directly”. There is simply no way that justice can be attained in modern society through private initiative alone.

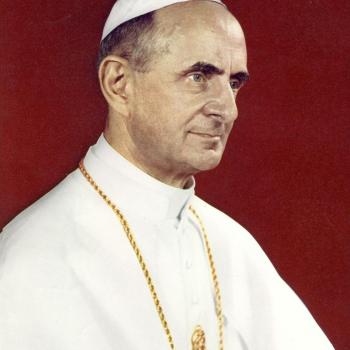

Benedict also notes that charity goes beyond justice, but never lacks justice: “I cannot give what is mine to the other without first giving him what pertains to him in justice”. Pope Paul VI says we should make sure that “the demands of justice be satisfied lest the giving of what is due in justice be represented as the offering of a charitable gift”. Or as St. Augustine said so simply, “charity is no substitute for justice withheld”.

Of course, this is all related to how to the Church sees the role of the state, which is quite different from the contemporary fad on the American right to define its role in minimal terms – securing public order and basic rules of the road for private freedom to flourish. This approach – which sees individual liberty and freedom from coercion as the bedrock of the social order – is totally at odds with Catholic social teaching. After all, we are the children of Aristotle, not John Locke. And so Pope Leo XIII could confidently declare in Immortale Dei that “Man’s natural instinct moves him to live in civil society…no society can hold together unless someone be over all, directing all to strive earnestly for the common good…every body politic must have a ruling authority, and this authority, no less than society itself, has its source in nature, and has, consequently, God for its Author”.

Clearly, then, it is the duty of the state to support the common good – this is a constant refrain throughout Catholic social teaching. As Pope Benedict puts it in Deus Caritas Est, “the just ordering of society and the State is a central responsibility of politics”. Pope John XXIII in Mater et Magistra is even more direct: “As for the State, its whole raison d’être is the realization of the common good in the temporal order. It cannot, therefore, hold aloof from economic matters”. So it has a role in distributive justice, in protecting the poor and the wage earner, and in creating favorable conditions for all members of society to flourish. In the modern era, the state’s role is likely to increase, not diminish – this was a point made by Benedict XVI in Caritas in Veritate.

3. We should draw a hard line between non-negotiable teachings and prudential judgments.

Catholic social teaching stems from a single source – the innate dignity of every human person made in the image and likeness of God, defined not by autonomy but by interpersonal relationships, made not for himself but for gift. As Pope Benedict says clearly in Caritas in Veritate, “Clarity is not served by certain abstract subdivisions of the Church’s social doctrine … a single teaching, consistent and at the same time ever new”. The book of nature is one and indivisible, he says.

Of course, this fallacy, like all errors, contains a kernel of truth. There are general moral principles that must always be accepted, including the sacredness of life, solidarity with the poor, the pursuit of peace etc. But translating these principles into concrete action means taking a few steps down the ladder of certainty. We are applying universal principles to specific facts and circumstances. We make prudential judgments. We are often fumbling in the dark.

This applies pretty much across the board. Just look at abortion, for example, often seen as the ultimate “non-negotiable” issue. And indeed it is. But when we look at how policy effects abortion, we are delving into prudential judgment. For example, you might be asked to choose between a “pro-life” candidate whose main contribution would be to appoint justices who might overturn Roe v. Wade, while doing all kinds of other harm to the social order at the same time, or a “pro-choice” candidate who fights all attempts to restrict the availability of abortion, but nonetheless supports the kinds of economic and healthcare policies that will reduce the incidence of abortion. Such a choice involves a prudential judgement, one we are required to make.

It is exactly same with the principles of economic justice – solidarity, subsidiarity, the preferential option for the poor. We make imperfect assessments of how various policy proposals will affect the common good.

So far so good. But it is here that people go wrong. They use the badge of “prudential judgment” as a kind of “get out of jail free” card. They wave their hands in the air, and say opinions differ, and so we must leave it at that. Here’s the problem: if we do this, we are not properly applying practical reason to the task at hand – we are showing little interest in “truth”. Just consider the Romney-Ryan economic plan. The evidence is clear: the poor would suffer disproportionately, as two-thirds of their spending cuts are focused on programs that benefit the poor, while about 50 million extra people (from the Obama status quo) lose health insurance. The rich benefit disproportionately. And debt rises beyond the baseline, given the extent of the upper-income tax cuts.

How can this be aligned with Catholic social teaching? It cannot, unless you make crazy assumptions that defy reason and logic. I think the only way to actually defend it is to assume that it has no chance of ever being implemented!

I believe what we are seeing is the cloak of “prudential judgment” being used to disguise deviation from the underlying principles of Catholic social teaching themselves. And we have evidence for this – both Romney and Ryan are on record defending the individualism associated with Ayn Rand, and the liberalism of autonomy and self-determination where you “define happiness for yourself”, as Paul Ryan put it in his convention speech.

People in this camp also seem to be in the habit of defining reality for themselves! It goes back to Elizabeth Anscombe’s seminal criticism of Cartesian psychology, where “an intention was an interior act of the mind which could be produced at will”. Anscombe goes on: “if intention is all important – as it is – in determining the goodness or badness of an action, then, on this theory of what intention is, a marvellous way offered itself of making any action lawful. You only had to ‘direct your intention’ in a suitable way. In practice this means making a little speech to yourself: “What I mean to be doing is…”

Anscombe was talking about the targeting of innocents in war. But we could say the same thing about economic policies. If “I have no intention of hurting the poor, the unemployed, or the uninsured”, then anything goes. But it doesn’t. And therein lies the problem.