We all know now that Pope Francis didn’t say that our pets are going to Heaven. What he said was:

Sacred Scripture teaches us that the fulfillment of this marvelous plan cannot but involve everything that surrounds us and came from the heart and mind of God.

But that doesn’t answer the question for us as to whether they are indeed going to Heaven or not. And, as Jeff Schweitzer puts it well, it’s not enough to ask if our pets are going to heaven. We have to ask then about all other creatures too. He concludes:

Face it; we all know that viruses, bacteria, plants and some animals like sponges are not going to heaven. And we know that because of our instinct for what it means to be intelligent, self-conscious and self-aware.

But is that true? I have argued that, on the contrary, we can be fairly certain that all creatures, from the most intelligent to the smallest subatomic particle are indeed going to Heaven. And the reason is the mystery that we celebrate in a few days.

One of our hangups about this is the so-called immortality of the human soul. As I hear constantly reiterated: Human animals have immortal souls, but other animals don’t. I’ve never been convinced by arguments for the immortality of the soul, either made by Socrates or by Aquinas. I tend rather to agree with Karl Rahner:

From the perspective of a genuine anthropology of the concrete person, in this question we are neither justified nor obliged to split man into two “components” [body and soul] and to affirm this definitive validity [immortality] only for one of them. Our question about man’s definitive validity is completely identical with the question of his resurrection, whether the Greek and platonic tradition in church teaching sees this clearly or not (my emphasis).

In other words, if we can get over our Neoplatonic hangover, then we’ll be able to move beyond the notion of an “immortal soul,” and accept the much more Jewish and biblical understanding of “natural bodies” and “spiritual bodies” (1 Cor 15:36-49). Spiritual bodies are bodies that have been raised to life in Christ.

But still, why should we believe that all of created reality will get raised to life with Christ? Aside from important passages from Scripture such as Romans 8:21 and Colossians 20, I think we can turn to the well known Cappadocian dictum, that what has not be assumed has not been redeemed. As I explain:

Elizabeth Johnson has coined the term “deep resurrection” to reflect on the eschatological hope that exists for all of created reality. Johnson derives the term deep resurrection from the idea of “deep incarnation” put forward by Danish theologian Niels Gregersen. For Gregersen, St. John the Evangelists’ use of sarx (usually translated “flesh”) describes the incarnation in a far more extensive way than the language of soma (“body”) eventually adopted by the Council of Chalcedon (the Council that set the standard for how the Church still talks about the incarnation). John’s language draws on the Hebrew meaning of the term for which sarx is the Greek Septuagint translation, i.e., all physical reality. The flesh of Christ taken up in the incarnation, therefore, includes all of physical reality. Similarly for Johnson, deep resurrection, drawing upon deep incarnation, means precisely that in the resurrection of Christ’s physical body, all physical reality enjoys the promise of being raised. By taking on our “flesh,” Christ took on the reality of all created existence, and by rising from the dead, he offers the promise of resurrection, not only to self-conscious, conscious, or sentient beings, but to all created beings that have ever existed.

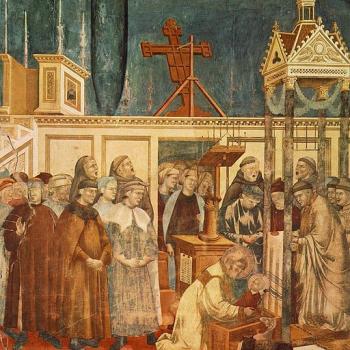

If all creation has been “assumed” in the flesh of Christ, then all creation awaits the same redemption and transformation of us human animals. Christmas matters, not just for us, but for the animals that stood around the manger of Christ, and for any creature that ever has or ever will inhabit this universe.