“Thank goodness I’m not like those people who talk during Mass…” “Thank goodness I’m blessed with so many gifts…” “Thank goodness I’m not like those women who wear immodest clothes…” “Thank goodness I’m a practicing Catholic…” “Thank goodness I’m not like one of those people who are alcoholic or drug addicts…” Have not all of us said something along these lines at least once in our lives?

This past Sunday’s Gospel is truly a challenge for all of us who constantly thank God “for making us so ‘great.’” In the words of Luke, Jesus “addressed this parable to those who were convinced of their own righteousness and despised everyone else” (Lk 18:9). Sounds like this parable never loses its relevance, since we are often convinced of our “own righteousness” and are very quick in pointing out how we are “doing everything right,” but others are not.

The Pharisee in the parable “spoke a prayer to himself” (note that he speaks the prayer to himself and not to God!) and thanked God for not making him “greedy, dishonest or adulterous” like the rest of humanity or the tax collector (18:11). The Pharisee did everything right: he fasted twice a week and paid tithes on his “whole income” (18:12). On the other hand, the tax collector “would not even raise his eyes to heaven,” because he was so aware of his sins and instead prayed “O God, be merciful to me a sinner” (18:13).

In Flannery O’ Connor’s short story, Revelation, the main character of the story, Mrs. Turpin, thanks God for basically making her “white” and not “white trashy” and for giving her and her husband plenty of land that set them above most other people in society, economically speaking. Ironically enough, at the end of the story Mrs. Turpin has a revelation. She sees these people that she looked down upon during the whole story (“blacks,” “white trash,” those living in poverty) marching up to heaven and those like her and her husband were actually at the end of the line—they were being saved just like everybody else, but not received in heaven with special treatment just because of the “special blessings” Mrs. Turpin thought she and her husband had received.

This past Sunday’s Gospel is a tricky one. Just when we think that we are not like the Pharisee, we actually become like the Pharisee himself: we look down upon him and say “Thank God for not making me like him!” To be truly humble like the tax collector and acutely aware of our sins, we need to go through a metanoia: a radical conversion—a turning away from sin and turning towards God. Once we have reached that radical conversion, we no longer thank God for being so good to us and for the “special blessings” he has given us, because we are so “wonderful and lovable.” When we think in such a way, we turn into the Pharisee and our prayer is spoken to “ourselves” rather than being elevated to the heavens like the tax collector’s prayer. Instead, we thank God for loving us because He himself is love (1 Jn 4:8) and, consequently, “if God so loved us, we also must love one another” (4:11).

The more we love God, the more we become aware of our sins and the more we understand that the consequences of sin are not exclusively personal just as the effects of true charity are not contained in a single individual. Rather, sin and charity–in diverging ways–have communal effects that affect the Mystical Body of Christ and the greater good of mankind. As John Paul II said in his encyclical Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, “we are all really responsible for all” (no. 38); therefore, our words, actions or lack thereof, affect not only ourselves, but everyone else for whom we are responsible and accountable for and we will be judged accordingly on the last day (Mt 25:31-46).

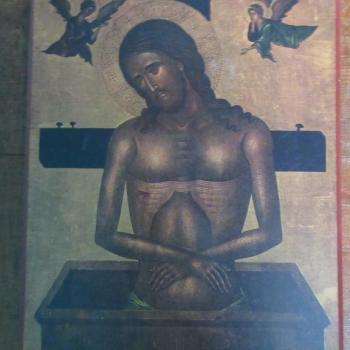

I recently went on a silent retreat and the priest who was directing it said something that opened my eyes. He said that whenever we start feeling comfortable with ourselves and acknowledging how much we love and care for other people, we should ask ourselves whether we are truly worried about the salvation of souls to the point that we become scandalized and disturbed that so many people sin in this world. Whenever we see our family members, friends or even strangers sinning in “obvious” and terrible ways, do we just say to ourselves: “Well, I guess they are working pretty hard to get a non-stop ticket to hell” and walk away? Or do we feel so responsible for our neighbors and their salvation that we would give our lives for them so they can be saved? God did that for us on the cross, but can we pick up that cross? That is what Jesus meant whenever he said “Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me. For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake and that of the gospel will save it” (Mk 8:34-35).

Once again, the message of the Gospel is the gift of self. The Christian who truly understands the implications of self-emptying and the pouring out of oneself cannot say: “Thank God I am not like…”, but realizes that the love of God has been poured out to all without exception and says instead like the tax collector “O God, be merciful to me a sinner” (Lk 18:13).