Now Featured in the Patheos Book Club

The God Who Weeps

How Mormonism Makes Sense of Life

By Terryl and Fiona Givens

Chapter Four

None of Them Is Lost

God has the desire and the power to unite and exalt the entire human family in a kingdom of heaven, and except for the most stubbornly unwilling, that will be our destiny.

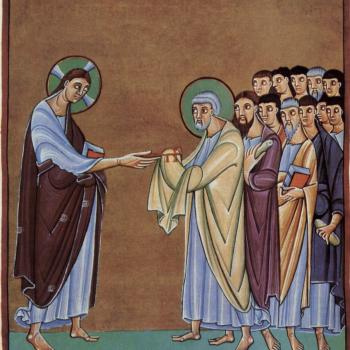

"This is the father's will . . . that of all which He hath given me I should lose nothing."

God is personally invested in shepherding His children through the process of mortality and beyond; His desires are set upon the whole human family, not upon a select few. He is not predisposed to just the fast learners, the naturally inclined, or the morally gifted. The project of human advancement that God designed offers a hope to the entire human race. It is universal in its appeal and reach alike. This, however, has not been the traditional view.

Some Christians believed hell to be a more populous destination than heaven. The Bible had declared that "the gate is narrow and the road is hard that leads to life, and there are few who find it." Just how few was a matter of recurrent speculation. One popular friar of the early eighteenth century, St. Leonard of Port Maurice, sermonized on "The Little Number of Those Who are Saved," reviewing the opinions of church authorities from St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas up to his own day. Most everyone he surveyed agreed that "the greater number of Christian adults are damned." Non-Christians and unbaptized children weren't even possible candidates for salvation. He relates one visionary account that put the proportions at two souls saved and three in purgatory for every thirty-three thousand damned to hell. Another source gave odds of three saved out of sixty thousand.

By mid-eighteenth century, two religious titans of the Anglo-Saxon world, former allies, were publicly debating the question of just how many people were destined for an eternity in hell. In 1738, John Wesley sermonized against the "blasphemy contained in the horrible decree of predestination." His objection was that the doctrine consigned "the greater part of mankind [to] abide in death without any possibility of redemption." Popular preacher George Whitefield published his response in 1740, attacking the idea that "God's grace is free to all." This was tantamount to "propagating the doctrine of universal redemption," he protested, insisting that only a select few were chosen for salvation, while "the rest of mankind ... will at last suffer that eternal death which is its proper wages."

Whitefield's language raises the question about what kind of thinking underlies our inherited notions about salvation and damnation. We have described our ascent to earth as a costly, sometimes harrowing, education in the school of eternal development. But we know that more than simple error is involved in our mortal experiences. Guilt is a real—and legitimate—human emotion, and it signals that sin is more than an outdated religious concept. With his reference to mankind's "proper wages," Whitefield was alluding to the doctrine of Original Sin, which he accused Wesley of denying. For if we all sinned in Adam, we would all merit damnation in consequence. According to that school of thought, it would be surprising if many were saved and few were damned, not the other way around.

However, if we reject Original Sin and inherited guilt as unreasonable, then what do we mean by salvation in the first place? Who is in need of rescue, and from what? If life is meant to be educative, and we are learning from our errors, why does the threat of divine retribution loom over our heads? Even if we admit that we are responsible for our own poor choices, why would God punish us for mistakes made along our path to moral growth and betterment?

Job's visitor Elihu asked this same question, trying to fathom the link between Job's behavior and his standing before God. His question still rings loud in our ears: "If you have sinned, what do you accomplish against him? And if your transgressions are multiplied, what do you to him?" Why do our actions, for good or ill, matter to God, in other words, and why would He choose to punish or reward accordingly?

We have already established that God is invested in our lives and happiness, because He chooses to be a Father to us. His concern with human sin is with the pain and suffering it produces. Sympathy and sorrow, not anger and vengeance, are the emotions we must look to in order to plumb the nature of the divine response to sin. In the biblical book of Judges, Israel repeatedly forsakes the worship of Jehovah, and suffers defeat and oppression at their enemies' hands as a result. Eventually, the Israelites repent and cry unto the Lord for mercy. In reply, He reminds them of their recurrent faithlessness.