Hell, in the sense of permanent alienation from God, a stunting of one's infinite potential, must exist as an option if freedom is to exist. That anyone would choose such a fate is hard to imagine, and yet some of us choose our own private hells often enough in the here and now. The difference is that at present we see "through a glass darkly." Our decisions are often made in weakness, or with deficient will or understanding. We live on an uneven playing field, where to greater or lesser degree the weakness of the flesh, of intellect, or of judgment intrudes. Poor instruction, crushing environment, chemical imbalances, deafening white noise, all cloud and impair our judgment.

Hardly ever, then, is a choice made with perfect, uncompromised freedom of the will. That, we saw, is why repentance is possible in the first place. We repent when upon reflection, with a stronger will, clearer insight, or deeper desire, we wish to choose differently. To be outside the reach of forgiveness and change, one would have to choose evil, to reject the love of a vulnerable God and His suffering son, in the most absolute and perfect light of understanding, with no impediments to the exercise of full freedom. It is not that repentance would not be allowable in such circumstances; repentance would simply not be conceivable. No new factor, no new understanding, no suddenly healed mind or soul, could abruptly appear to provide a basis for reconsideration or regret.

For us lesser mortals, who never attain such lofty heights of intellect and will, repentance and change continue as long as our striving does. God would not have commanded us to forgive each other seventy times seven, if He were not prepared to extend to us the same mathematical generosity. He seems determined to demonstrate that when we make regrettable choices we are not really choosing what the "better angels of our nature" want to choose. Come, try again, He seems to be saying, like a patient tutor who knows his student's mind is too frozen with fear to add the sums correctly.

Why else would the Lord's strategies be so rife with interventions and second chances? Samuel was called three times in the night, before he recognized his Lord. It took a bright light and a voice from heaven to capture Saul's attention. Who knows how many other potential disciples will find their road to Damascus only on the other side of life's veil? Why should God not there as well as here persist in His efforts to gather His children, as a hen its chicks? Why not believe that "His hand is stretched out still?" If we fall short of salvation, it will be because our cumulative choices, our freely made decision to reject His rescue, have put us beyond His reach, not because His patience has expired.

The idea is certainly a generous one, and it seems suited to the weeping God of Enoch, the God who has set His heart upon us. If some inconceivable few will persist in rejecting the course of eternal progress, they are "the only ones" who will be damned, taught Joseph Smith. "All the rest" of us will be rescued from the hell of our private torments and subsequent alienation from God. "All except" the intractable will be saved, for God will force no man to heaven.

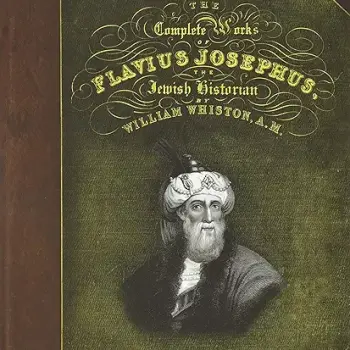

The book of Malachi ends with a cryptic prophecy of Elijah's return to the earth, when He will "turn the hearts of parents to their children and the hearts of children to their parents, so that [the Lord] will not come and strike the land with a curse." Jewish tradition, full of anticipation and yearning, weaves this interpretation: At the coming of the great judgment day, "the children . . . who had to die in infancy will be found among the just, while their fathers will be ranged on the other side. The babes will implore their fathers to come to them, but God will not permit it. Then Elijah will go to the little ones, and teach them how to plead in behalf of their fathers. They will stand before God and say, 'Is not the measure of good, the mercy of God, larger than the measure of chastisements? . . . [May they] be permitted to join us in Paradise?' God will give assent to their pleadings, and Elijah will have fulfilled the word of the prophet Malachi; He will have brought back the fathers to the children."

The beauty of this story is in its intimation that any conception of heaven worth pursuing is inseparable from reconciliation—not just to God, but also to our loved ones, those of our household and those of generations past. One might even read this prophecy, as indeed we do, as suggesting that the living may co-participate in the ongoing work of human redemption. We do not just share good tidings with the living. We can seek out our ancestors in a gesture of remembrance and respect, pray for their welfare, perform on their behalf those sacred ordinances that signify their participation in the family of Christ.

If Christ truly preached to the spirits who had in former days upon the earth been disobedient, then it makes sense to assume that the great work of ministry continues there. We find it reasonable to believe, along with Paul, that "neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor heights, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God." One is reminded here of the poet's plea that "God, lover of souls," will "complete thy creature dear O where it fails, / Being mighty . . . , being a father and fond."

As a mighty God, He has the capacity to save us all. As a fond father, He has the desire to do so. That is why, as Smith taught, "God hath made a provision that every spirit can be ferretted out in that world" that has not deliberately and definitively chosen to resist a grace that is stronger than the cords of death.