The key word in this week's meditation is "down." It is a metaphorical term, and as such requires thinking about what is being compared to what. Critics, for example, may charge that Christians still cling to a stone-age notion of deity "up there," to be refuted by contemporary cosmology. (There is a story that the first cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, proudly proclaimed that once in space he did not see God. The story, it turns out, was a complete fabrication, as Gagarin was a devout Orthodox Christian and the Soviets put the words in his mouth.)

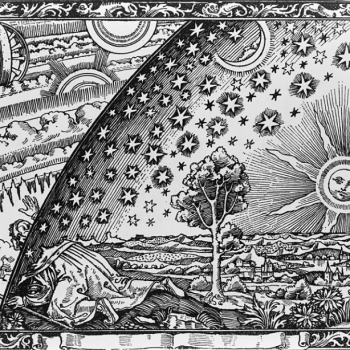

To be sure, ancient Hebrew cosmology—and indeed, early Christian cosmology, which followed Ptolemy's model of the cosmos up till the late middle ages—did hold that the heavens were above the earth. The Christian claim that Jesus "came down from heaven," then, was a reflection of Jesus' self-description in the gospel of John: "I am the living bread come down from heaven" (6:51). Accordingly, early Christian kerygma (proclamation) focused on a dual movement of God "down" to human beings in order that he might raise them "up" to divinity. We see such an image, for example, in the Philippians hymn (2:5-11):

Have among yourselves the same attitude that is also yours in Christ Jesus, Who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God something to be grasped. Rather, he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, coming in human likeness; and found human in appearance, he humbled himself, becoming obedient to death, even death on a cross. Because of this, God greatly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, of those in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

The theological terms that developed in the early Church in response to this notion of God raising humanity to the heavens are theosis (Greek for "becoming God") and divinization (a Latin translation of the same idea). The Catechism of the Catholic Church (460) puts it this way:

The Word became flesh to make us "partakers of the divine nature": "For this is why the Word became man, and the Son of God became the Son of man: so that man, by entering into communion with the Word and thus receiving divine sonship, might become a son of God." "For the Son of God became man so that we might become God." "The only-begotten Son of God, wanting to make us sharers in his divinity, assumed our nature, so that he, made man, might make men gods."

The citations in that section of the Catechism are to 2 Peter 1:4, and to St. Irenaeus and St. Athanasius, both of whom were critical in the development of Christological doctrines of the Council of Nicea. All point to the same idea: Christ's incarnation was God's desire to draw people to himself by becoming one of us, in order to lead us away from sinful desires to salvation.

One of the early images of the Church was that of a ship, the barque of Peter, sailing along dangerous seas to save souls. (Indeed, to this day the main part of a large church is called a nave, from Latin navis and Greek naus meaning "ship.") The basic Christological insight of the creed follows this imagery: Jesus' "coming down" was rather like the way a ship's captain might send someone down into the ocean to save someone from drowning. The two biblical images that inspired this image are Noah's ark, the ship that preserved humanity from destruction, and Peter's walking on the water toward Jesus (Mt. 14: 22-33). The latter story suggests Jesus' role as the one who saves us from drowning and provides comfort in the storms of life. In any case, the image of "coming down" is meant to suggest that human beings of themselves are unable to create their own salvation, caught as they are in a world of competing desires and temptations. They need a savior, a lifeguard.

A final parable might help illustrate what the creed proposes in saying that Jesus came down from heaven for us human beings (anthropous) and for our salvation. There was once a flock of geese wandering around a farmer's barn when a terrific hailstorm began to fall. The farmer, feeling pity for the beautiful birds, hoped to move them to safety in his barn. He threw on a raincoat and ran to the barn door, opening it to let them inside. But the geese were scared of the man and waddled off in the opposite direction, still getting pelted by huge hailstones. The farmer, wishing he could assure them of his intentions, desperately wanted to become a goose to lead the others into his barn.

The creed suggests that the Father is like the farmer, and that Jesus is the goose who leads us geese into safety. He became one of us in order that he might save us.

12/2/2022 9:05:39 PM