He liked to say he "grew up with the Brooklyn Bridge" on the Lower East Side. As the first Catholic to run for president on a major party ticket, Al Smith's was the classic rags to riches story. It began in gaslight era New York, when Trinity Church was the city's tallest building, and ended in the Empire State Building. Rising from clerk to CEO, Al Smith always considered himself an Irish Catholic kid from the Fourth Ward. He believed it was the best place in the world to grow up, a diverse community where everyone knew and looked out for each another.

An icon of Irish America, Smith was also Italian and German. For his family, the neighborhood's centerpoint was St. James Church, founded fifty years earlier by Felix Varela. From cradle to grave, St. James met every need: religious, educational, and social. Although Al left the parish school early (after his father's death), he was active in the theater group, learning public speaking techniques that served him well in politics.

These were the days of Tammany Hall, the political machine that dominated New York for a century. Although popularly associated with forces of corruption, by Smith's time it was embracing reform. As a young man, Smith would work his way up from the Fulton Street Fish Market through minor offices into the State Assembly. Although his formal education was limited, he committed himself to learning the art of lawmaking, and he succeeded.

The Triangle Fire of 1911, in which 146 factory workers died, marked a turning point for Smith: from politician to advocate. As part of the investigative commission, what he saw changed his life: single mothers working 120 hours a week and children working eighteen hours a day. When one child was asked how long she had been working, she answered "Ever since I was." Among other things, the commission helped ban child labor under fourteen, made sprinklers mandatory in factories, and required seats for all, irrespective of gender or color.

Imbued with what one biographer calls "common sense and a belief in decency," Smith became an identifiable public figure, with his brown derby and cigar, his ability to captivate a crowd, and what a peer called "his 100 percent frankness." A biographer notes that "the stage was his to command." A friend said that "vitality goes out from him like a flood." From the assembly he aspired to the governorship. Beginning in 1918, he served four terms. Here he came into his own politically, as a champion of the common man and woman.

As governor, he fought against discrimination, for workers' rights, and for decent housing. When a colleague complained about "rabble" moving into his community, Smith replied: "Rabble? That's me you're talking about." By 1924, he was emerging as a national leader in the Democratic Party during a Republican-dominated decade. (Taking credit for the era's prosperity, Republicans promised a "chicken in every pot.") Although Prohibition was the law of the land, Smith supported its repeal. And he unsuccessfully fought to have the Ku Klux Klan outlawed.

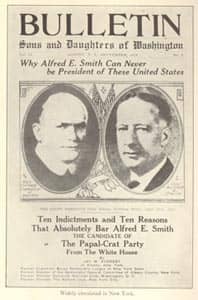

Anti-Catholicism was sweeping the nation at a level unseen since the days of the Know-Nothings. Oregon attempted to ban Catholic schools. Florida's governor warned of a Vatican takeover, and the Klan spread nationwide, stressing the Catholic "menace" to America. (At its height, national membership reached five million.) But nothing typified the era's religious hostility like the 1928 presidential campaign, when Alfred E. Smith dared run for the nation's highest office.

In Oklahoma, a minister said a vote for Smith was a vote against Christ. (When an opponent referred to papal encyclicals, Smith reputedly asked a friend, "What the hell is an encyclical?") Protestants envisioned the pope taking over the country. One journal predicted

. . . a confessional box in the White House, and the secrets of the Government whispered into the ear of a representative of the Vatican . . . [Smith] will be as a President what he has been as a Governor, the pliant tool of the most Christless system of tyranny the world has ever known.

Although he received the largest popular vote of any Democratic candidate, he still lost by a wide margin. Most scholars agree that the religious factor (along with a decade of Republican prosperity) sealed Smith's fate.

His defeat was a serious blow to Catholics, reminding them that they were still outsiders. The question still remained: could Catholics be "real" Americans? Would their religious obligations conflict with their political ones? It would be another three decades before John F. Kennedy answered that question definitively.

In the aftermath of the election, a jaded Smith moved away from politics, becoming president of the corporation that built the Empire State Building. In 1932, he attempted to win the Democratic nomination once more, but lost to Franklin D. Roosevelt. Some think he never quite forgave Roosevelt for this, and during the 1930s he opposed many of the president's measures. Smith called him "the kindest man that ever lived, but don't get in his way."