In links related to recent the recent headline, "Down Syndrome Reversed in Newborn Mice with Single Injection" one could find a number of articles touting the promises of curing Trisomy 21: "Cough Syrup could help with Down Syndrome," blared one; "Gene switches off Down Syndrome" went another.

The recent buzz is that science may eventually allow people with this genetic condition improve their independence, memory, and overall capacity to process, absorb, and retain information.

As a mother of a special-needs child, I belong to a Facebook group, Mommies of Miracles, wherein one woman rejoiced openly at hearing that buzz. I could not judge her. She has been following the research for years, and now, "Injections that cure Down syndrome in a single dose!" The possibilities of re-ordering the prospects for kids like hers and mine loom not as a pipe dream, but as a reality in some perhaps not-too-distant future. It sounds like a gift.

I read the articles. My head swims with the possibilities that my son might not be trapped forever in a silent world, in a non-potty trained world, in a not-on-your-own-in-this-life-ever world. I waited to feel the joy, the excitement, the overflowing enthusiasm about the prospect. But I did not.

Was there something wrong with me? I wondered, did I not want my son to thrive? Of course I did! He had had open-heart surgery at two months, and my throat still gets a lump at the mere memory of having to surrender him to the surgeon's care. I love that he runs and jumps and climbs now, and that he has no memory of those events that still clutch at my heart on occasion.

Certainly I want him to be able to live on his own, to be able to hold a job, to be able to function in the world. I see his younger sister—two years his junior—bypass him in language, in understanding, in capacity, and think that I'd like him to at least be on par with her. I'd like him to one day be able to attend the same school his sibling attends.

So, why am I holding onto the way my son is now? Why am I not jumping for joy that our shared cross could be eliminated with a pill or a shot?

Because he is precious now, and who he is can't be divorced from his condition. He calls us to love him for himself—as is -- to be valued for his being, as opposed to what he can accomplish, and "do."

Last week, having finished folding all of the laundry, I counted: thirteen baskets sat in the main room, brimming with clothes. I'd called my children to come get their things. No one budged. They were lost in the worlds of Kindle, homework, computers, television, and toys. My son had been playing with his trains. He came over and picked up his younger sister's basket.

Wordlessly, he began carrying it toward the stairs. His silent witness caught everyone else's attention, and they quickly assembled to get their hampers to their respective rooms, and even his younger sister got into the act; she helped him with carrying her own.

Sometimes the world needs a bit of silent witness, the kind that isn't found in the ivy leagues or board rooms or fast lanes inhabited by the polished, educated elite. Any of his five sisters or three brothers could have picked up their laundry at my first call, but they didn't, until they were inspired by my son's willingness to act. The witness of his obedience was better understood through the filter of his visible brokenness.

I think back to a quote I read in high school. Though I cannot remember the writer, the line stuck then and resonates now, "A joyful child reminds us of God the Father, and a crippled one, of His Son."

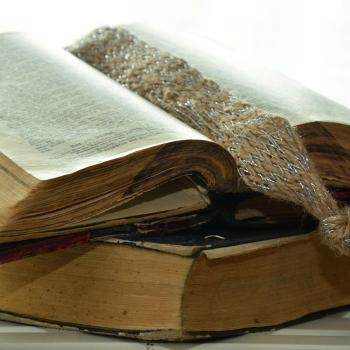

My son is both joyful and handicapped, and so he calls us to love more deeply than we might be inclined to, absent his trials. Perhaps I am too needy of the reminder, but I recently looked at the gospel and read, "No one tears a piece from a new cloak to patch an old one. Otherwise he will tear the cloak. Likewise, no one pours new wine into old wineskins. Otherwise the new wine will burst the skins and it will be spilled and the skins will be ruined. Rather, new wine must be poured into fresh wineskins. And no one who has been drinking old wine desires new, for he says, 'The old is good'" (Lk. 5:36-39).

Curing Down Syndrome would mean rewriting who my son is on a genetic level, putting a new patch on an old skin. This is not like fixing a broken arm or laser surgery to restore an eye to its more youthful capacity. This is tinkering with how he understands and relates to the world—possibly with who he is. Could it possibly cause the skin to burst and the wine to be spilled? How do I reconcile knowing that he is "wonderfully and fearfully made" with going in and reworking my son's DNA?