- Profession: Midwife

- Lived: July 20, 1591 - August, 1643 (Reformation)

- Nationality: English

- Known for: Standing up to male leadership of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and being kicked out

- Fun Fact: Some believe that Nathaniel Hawthorne's "The Scarlet Letter" was inspired by Anne Hutchinson's experiences. Hawthorne's great-great-great-grandfather was a magistrate in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

- Fun Fact: New York's Hutchinson River and Hutchinson River Parkway (known to locals as the Hutch) are named after Anne.

Anne Hutchinson is a key figure in the history of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Puritanism. She is the daughter of a Puritan Anglican clergyman from London who had been convicted of heresy and spent two years in prison before she was born, but who had been released and allowed to preach again. He made sure Anne was well educated, and part of her childhood was spent in cosmopolitan London. After her father died, Anne Marbury married William Hutchinson and they started following the Puritan Anglican preacher John Cotton in the port town of Boston in Lincolnshire.

Cotton and some other Puritans were focusing more on the saving power of grace and less on purity in behavior. The focus on grace led to greater equality between clergy and laypeople, and especially, a greater role for women, since the grace of God is equally in all. Anne, with her extensive education and cosmopolitan London experience, was well-positioned to thrive at the frequent informal gatherings among laypeople to discuss scripture and recent sermons, and soon she was leading her own, teaching many in her own take on the sermon material and scripture. And so things continued for over two decades. Eventually, though, Cotton was removed from the pulpit and ordered to stand trial for heresy; he fled to the United States, and Anne, at 43, along with her husband and ten children soon followed.

In the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Anne became a midwife, through which she moved among the women of the colony, talking about faith and offering spiritual guidance. Soon, she began again to host a weekly discussion group in her home, in which she taught in response to the sermon and readings. These expanded to include men as well, including the governor of Massachusetts. Anne began elaborating more and more on salvation through grace, not works; and while within the bounds of her mentor and pastor, John Cotton’s, teachings, this clashed with conventional Puritan views. As her popularity grew, the colony’s ministers started to take more notice. Hutchinson declared that John Wilson, the senior pastor of the colony, who strongly disagreed on salvation through grace, lacked “the seal of the Spirit.” Folks started choosing sides, with the several ministers and many laypeople, including the governor, choosing the “free grace” side, and most ministers on the “preparation” or works side.

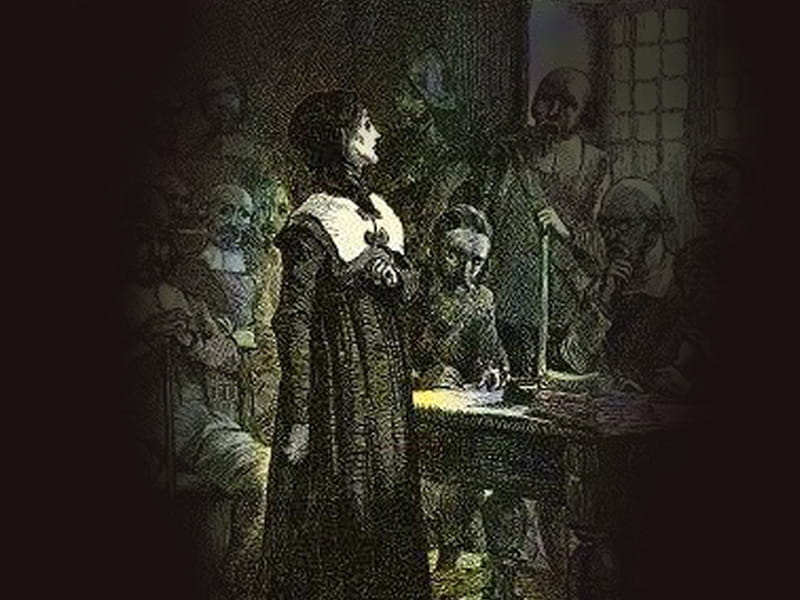

In what is known as the Antinomian Controversy, Hutchinson and Cotton and another minister were confronted. Antinomianism is an old and recurring heresy charge. It essentially means believing you are not bound by the Law. But it was a false charge here, and often is. What Hutchinson and others believed was that grace comes first and that if you are operating in grace, your actions will be within the Law. The accusations of unlawful and immoral behavior were false, and designed to underscore the danger of the theological view. Beyond theology, the ministers, and many of the public, saw this potential schism as a threat to the community, and opposed it on that count. In elections the following year, the citizens ousted the governor and those magistrates who were pro-free grace. Hutchinson was tried not for heresy, but for slandering a minister and troubling the peace. Her trial was shaky when Hutchinson denounced them and what they were doing under oath, leading instead to a charge of contempt of court. The other free grace minister had been kicked out of town already and Cotton waffled. The magistrates and ministers happily scapegoated the unordained Hutchinson rather than acknowledging there was a serious theological split in the community. (To many, it was the mere fact of her being a woman claiming to have greater authority than male leaders that was her crime.)

Hutchinson was put under house arrest while a second trial was prepared. Her like-minded mentor, John Cotton turned on her to save himself and counseled her to recant, which she reluctantly and sadly did. But it was not enough. Several of the ministers would not let it go, and turned the proceeding against her. She was banished from Massachusetts along with 75 supporters. Her husband and others had left earlier to stake out a new home, and they established Portsmouth (now in Rhode Island.) She and some followers met up with them. Several years later, her husband died and there were threats that Massachusetts was going to attack and seize the new Rhode Island communities. Hutchinson decided to leave New England entirely, travelling south with family and a few others, to Dutch New Netherland, in what is now the Bronx, New York. This might have been the end of the story, with the Hutchinson clan living out their lives there, but they found themselves in the middle of a war with the local Native Americans. In a skirmish, the entire Hutchinson clan including children and servants was killed save one child who was captured and raised by the natives for several years before being traded back.

Shockingly, her enemies in Massachusetts gloated publicly¬¬, saying the slaughter of her and her family was God’s just punishment. As America embraced the principle of separation of church and state, Hutchinson’s treatment by the Puritans—being tried in court, imprisoned and exiled —turned her into a hero of liberty. Her bold authoritative attitude in the face of male leaders turned her into a feminist hero. Hutchinson is honored with a feast day in the Episcopal Church calendar.

Cotton and some other Puritans were focusing more on the saving power of grace and less on purity in behavior. The focus on grace led to greater equality between clergy and laypeople, and especially, a greater role for women, since the grace of God is equally in all. Anne, with her extensive education and cosmopolitan London experience, was well-positioned to thrive at the frequent informal gatherings among laypeople to discuss scripture and recent sermons, and soon she was leading her own, teaching many in her own take on the sermon material and scripture. And so things continued for over two decades. Eventually, though, Cotton was removed from the pulpit and ordered to stand trial for heresy; he fled to the United States, and Anne, at 43, along with her husband and ten children soon followed.

In the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Anne became a midwife, through which she moved among the women of the colony, talking about faith and offering spiritual guidance. Soon, she began again to host a weekly discussion group in her home, in which she taught in response to the sermon and readings. These expanded to include men as well, including the governor of Massachusetts. Anne began elaborating more and more on salvation through grace, not works; and while within the bounds of her mentor and pastor, John Cotton’s, teachings, this clashed with conventional Puritan views. As her popularity grew, the colony’s ministers started to take more notice. Hutchinson declared that John Wilson, the senior pastor of the colony, who strongly disagreed on salvation through grace, lacked “the seal of the Spirit.” Folks started choosing sides, with the several ministers and many laypeople, including the governor, choosing the “free grace” side, and most ministers on the “preparation” or works side.

In what is known as the Antinomian Controversy, Hutchinson and Cotton and another minister were confronted. Antinomianism is an old and recurring heresy charge. It essentially means believing you are not bound by the Law. But it was a false charge here, and often is. What Hutchinson and others believed was that grace comes first and that if you are operating in grace, your actions will be within the Law. The accusations of unlawful and immoral behavior were false, and designed to underscore the danger of the theological view. Beyond theology, the ministers, and many of the public, saw this potential schism as a threat to the community, and opposed it on that count. In elections the following year, the citizens ousted the governor and those magistrates who were pro-free grace. Hutchinson was tried not for heresy, but for slandering a minister and troubling the peace. Her trial was shaky when Hutchinson denounced them and what they were doing under oath, leading instead to a charge of contempt of court. The other free grace minister had been kicked out of town already and Cotton waffled. The magistrates and ministers happily scapegoated the unordained Hutchinson rather than acknowledging there was a serious theological split in the community. (To many, it was the mere fact of her being a woman claiming to have greater authority than male leaders that was her crime.)

Hutchinson was put under house arrest while a second trial was prepared. Her like-minded mentor, John Cotton turned on her to save himself and counseled her to recant, which she reluctantly and sadly did. But it was not enough. Several of the ministers would not let it go, and turned the proceeding against her. She was banished from Massachusetts along with 75 supporters. Her husband and others had left earlier to stake out a new home, and they established Portsmouth (now in Rhode Island.) She and some followers met up with them. Several years later, her husband died and there were threats that Massachusetts was going to attack and seize the new Rhode Island communities. Hutchinson decided to leave New England entirely, travelling south with family and a few others, to Dutch New Netherland, in what is now the Bronx, New York. This might have been the end of the story, with the Hutchinson clan living out their lives there, but they found themselves in the middle of a war with the local Native Americans. In a skirmish, the entire Hutchinson clan including children and servants was killed save one child who was captured and raised by the natives for several years before being traded back.

Shockingly, her enemies in Massachusetts gloated publicly¬¬, saying the slaughter of her and her family was God’s just punishment. As America embraced the principle of separation of church and state, Hutchinson’s treatment by the Puritans—being tried in court, imprisoned and exiled —turned her into a hero of liberty. Her bold authoritative attitude in the face of male leaders turned her into a feminist hero. Hutchinson is honored with a feast day in the Episcopal Church calendar.

Back to Search Results