- Profession: Abbot

- Lived: January 12, 251 - January 17, 356 (Early Church)

- Nationality: Egyptian

- Known for: Father of monasticism

- Fun Fact: Anthony described his temptations as encounters with demons, centaurs, satyrs, and wild beasts, which attacked him, beat him and wrestled with him. This rich metaphorical language contributed to his popularity in the Middle Ages, and was elaborated on by writers and artists such as Hieronymus Bosch.

- Fun Fact: "Whoever hammers a lump of iron, first decides what he is going to make of it, a scythe, a sword, or an axe. Even so we ought to make up our minds what kind of virute we want to forge or we labor in vain." — Anthony of the Desert

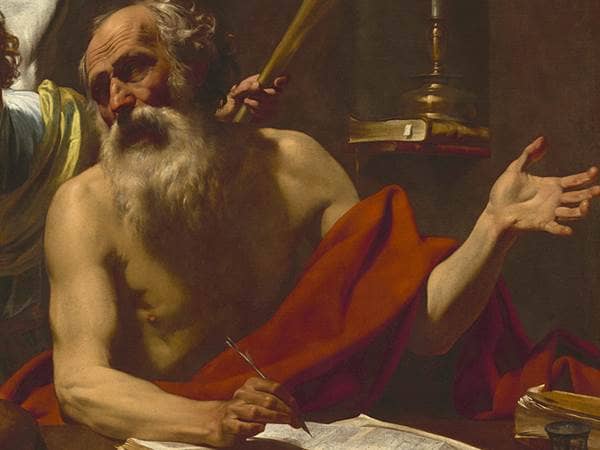

As Christianity became more of an organized religion, and especially after it became legal—then the state religion—and the days of martyrdom faded, some Christians who sought a path with greater sacrifice and greater purity started going into the desert to live as hermits—their days filled with devotion and prayer, and an ascetic lifestyle of minimal food, no possessions and limited interaction with others (an existing, though not particularly popular, practice in contemporary Jewish and Pagan cultures.) One of the earliest of these was Anthony, who was born in Egypt to a wealthy landowning family but had lost his parents at 18. When he heard the message of Jesus preached a year or two later, he sold or gave away all his possessions (sending his younger sister for whom he was responsible to a community of women sworn to virginity), and headed to the desert. He spent most of the rest of his life there.

Many others came to the desert—thousands eventually—and a community grew up around Anthony. He was not the only hermit, or the first, but he helped organize the communal life of his followers, and has come to be known as the founder of monasticism, two centuries before Benedict would organize monasteries more formally.

As a hermit, Anthony struggled with all the things an ascetic or a person alone with their thoughts for long stretches will face—boredom, temptations, acedia. He was probably illiterate, but Anthony’s struggles with these challenges of proto-monastic life, and his shared thoughts and insights, were recorded by devotees. Shortly after his death, Athanasius of Alexandria wrote a biography which was then translated into Latin. This became an extremely popular Latin Christian text, popularizing Anthony, and monasticism in general, throughout the medieval Christian world. Along with collections of teachings and sayings from what came to be known as the Desert Fathers and Mothers, in which Anthony figured prominently, he was an influential figure in the development of medieval Christianity.

Some of the practices of Anthony and the other Desert Fathers and Mothers, such as repetitive prayer and daily chanting of psalms, while maintained in Western monastic settings, have always been part of the regular fabric of spiritual life in the Orthodox world. Non-monastic Western Christianity rediscovered Anthony and the other Desert Fathers and Mothers in the 1950s and 60s, thanks to the work of Thomas Merton, prefiguring various modern forms of Christian contemplative practice such as centering prayer. And while some orders in medieval Christianity and since have engaged the surrounding world, Anthony represents the older tradition of building an alternative Christian community, cut off from the problematic secular world. This idea, which returns time and again, has been revived recently in Rod Dreher’s “Benedict Option.”

Many others came to the desert—thousands eventually—and a community grew up around Anthony. He was not the only hermit, or the first, but he helped organize the communal life of his followers, and has come to be known as the founder of monasticism, two centuries before Benedict would organize monasteries more formally.

As a hermit, Anthony struggled with all the things an ascetic or a person alone with their thoughts for long stretches will face—boredom, temptations, acedia. He was probably illiterate, but Anthony’s struggles with these challenges of proto-monastic life, and his shared thoughts and insights, were recorded by devotees. Shortly after his death, Athanasius of Alexandria wrote a biography which was then translated into Latin. This became an extremely popular Latin Christian text, popularizing Anthony, and monasticism in general, throughout the medieval Christian world. Along with collections of teachings and sayings from what came to be known as the Desert Fathers and Mothers, in which Anthony figured prominently, he was an influential figure in the development of medieval Christianity.

Some of the practices of Anthony and the other Desert Fathers and Mothers, such as repetitive prayer and daily chanting of psalms, while maintained in Western monastic settings, have always been part of the regular fabric of spiritual life in the Orthodox world. Non-monastic Western Christianity rediscovered Anthony and the other Desert Fathers and Mothers in the 1950s and 60s, thanks to the work of Thomas Merton, prefiguring various modern forms of Christian contemplative practice such as centering prayer. And while some orders in medieval Christianity and since have engaged the surrounding world, Anthony represents the older tradition of building an alternative Christian community, cut off from the problematic secular world. This idea, which returns time and again, has been revived recently in Rod Dreher’s “Benedict Option.”

Back to Search Results