- Profession: theologian

- Lived: 1225 - March 7, 1274 (Late Medieval)

- Nationality: Sicilian

- Known for: Leading figure of Scholiasticism; one of two most influential Catholic thinkers, with Augustine.

- Fun Fact: After authoring the 900,000 word cornerstone document of Cahtolic dogma, and much else, months before his death, Aquinas said, “I can write no more. All that I have written seems like straw.”

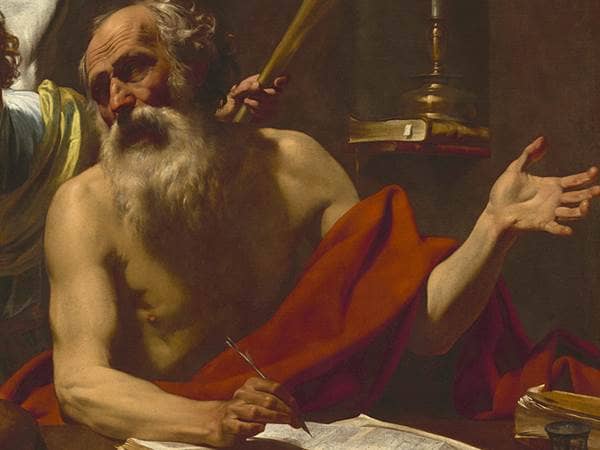

Arguably the most influential thinker of the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas was a Dominican priest born to an aristocratic family in Sicily. His older siblings were groomed for military and leadership roles, while as a younger child, as was typical, he was dedicated to the church. Before he could join the Benedictine monastery run by an uncle, however, Thomas encountered teachers from the new Dominican order, and through them, the philosophy of Aristotle.

To oversimplify horribly, there were two threads of Western intellectual thought in the Middle Ages. Most Judeo-Christian theological and philosophical thought for a thousand years had descended from Plato, and in Christianity, the work of Augustine, a Platonist—emphasizing symbolism, faith, and the unknowable deeper reality. In the 1200s with Scholasticism, Thomas Aquinas and the Dominicans rooted their intellectual pursuits in the Greek Rationalism of Aristotle, not Plato, and believed reason, analysis and debate were the path to Truth. This rational and legalistic approach, often called Thomism after Aquinas, has had vast influence on Roman Catholic and all Christian theology, and on the emerging social and philosophical views on reason which led to the Renaissance and Enlightenment. Aquinas studied and quoted Jewism medieval scholars including Maimonides, and in turn was translated and read by later Jewish scholars, influencing Jewish theology and culture to this day. Even among the many religious and philosophical thinkers and schools since that differ with Aquinas, that difference was often framed in relation to Thomist thought. Thomism dominated until the early hints of coming postmodernism suggested that reason and observation were not always so reliable, and it continues in the ongoing debates around these issues.

In the last decade of his life, Aquinas set out to write a complete collection on the Christian faith. The resulting “book,” the Summa Theologica, is a collection of 3,000 articles, each making a reasoned argument for one belief of the Catholic Church. The Summa remains as one of the cornerstones of Catholic dogma and debate. It is noteworthy for his citing of pagan philosophers, Jewish and Muslim theologians. Aquinas intended the Summa to be a beginner’s text for seminarians, and it is still used in Catholics and many Protest seminaries today. Though it’s formidable, to say the least, at about 900,000 words on 3,000 pages in five volumes. It is also incomplete, as Aquinas never finished it. Several months before his death, he said to a colleague, “I can write no more. All that I have written seems like straw.” This line is still debated, as to whether he meant that he had come to believe that the intricate rationalistic approach to which he’d devoted his life was misplaced, or that any written words pale next to authentic spiritual experience.

To oversimplify horribly, there were two threads of Western intellectual thought in the Middle Ages. Most Judeo-Christian theological and philosophical thought for a thousand years had descended from Plato, and in Christianity, the work of Augustine, a Platonist—emphasizing symbolism, faith, and the unknowable deeper reality. In the 1200s with Scholasticism, Thomas Aquinas and the Dominicans rooted their intellectual pursuits in the Greek Rationalism of Aristotle, not Plato, and believed reason, analysis and debate were the path to Truth. This rational and legalistic approach, often called Thomism after Aquinas, has had vast influence on Roman Catholic and all Christian theology, and on the emerging social and philosophical views on reason which led to the Renaissance and Enlightenment. Aquinas studied and quoted Jewism medieval scholars including Maimonides, and in turn was translated and read by later Jewish scholars, influencing Jewish theology and culture to this day. Even among the many religious and philosophical thinkers and schools since that differ with Aquinas, that difference was often framed in relation to Thomist thought. Thomism dominated until the early hints of coming postmodernism suggested that reason and observation were not always so reliable, and it continues in the ongoing debates around these issues.

In the last decade of his life, Aquinas set out to write a complete collection on the Christian faith. The resulting “book,” the Summa Theologica, is a collection of 3,000 articles, each making a reasoned argument for one belief of the Catholic Church. The Summa remains as one of the cornerstones of Catholic dogma and debate. It is noteworthy for his citing of pagan philosophers, Jewish and Muslim theologians. Aquinas intended the Summa to be a beginner’s text for seminarians, and it is still used in Catholics and many Protest seminaries today. Though it’s formidable, to say the least, at about 900,000 words on 3,000 pages in five volumes. It is also incomplete, as Aquinas never finished it. Several months before his death, he said to a colleague, “I can write no more. All that I have written seems like straw.” This line is still debated, as to whether he meant that he had come to believe that the intricate rationalistic approach to which he’d devoted his life was misplaced, or that any written words pale next to authentic spiritual experience.

Back to Search Results