It is too easy to oversimplify the point, but it is interesting that until about 1000 C.E., Christian depictions of Jesus focused on his life and, particularly, on his resurrection.

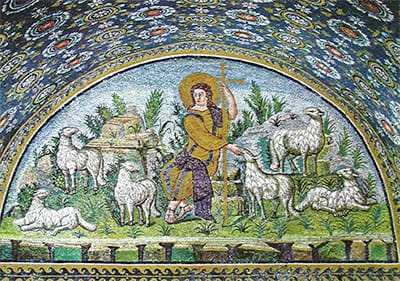

As perfect examples, consider the mosaics of Ravenna, Italy. This one in the tomb of Galla Placida is an excellent example, showing the resurrected Christ feeding his sheep:

And this portrayal of the Second Coming (in the church of San Vitale) shows it as a time of spring and joy rather than blood and horror:

Depictions of Christ's crucifixion only gradually play a central role in Christian iconography until they come to dominate in about 1000 C.E. Earliest Christians appear to have thought primarily of the resurrected Jesus as a shepherd and healer, as one who protects and blesses, rather than as one who suffers. The implication is that they understood what it means to be a Christian in terms of being shepherded and healed rather than in terms of suffering.

Of course that is not to say that the Christians of late antiquity and the early medieval world were unaware of Christ's suffering, nor that the cross played no role in their iconography or religious understanding. It is, rather, to make a point about Easter.

We can use Romans 6:8-11 as a text for thinking about that earlier perspective:

Now if we have died with Christ, we trust that we will also live with him: knowing that Christ, having been raised from the dead, will not die again; we know that death has no more lordship over him. In dying, he died to sin once and for all, but in living, he lives to God. In the same way, consider yourselves dead to sin but alive to God in Christ Jesus.

To be a Christian is to receive a new life. It is to live the divine life we find in Jesus the Messiah.

In the Book of Mormon the prophet Jacob expresses the same desire:

May God raise you from death by the power of the resurrection, and also from everlasting death by the power of the atonement, that ye may be received into the eternal kingdom of God, that ye may praise him through grace divine. (2 Ne. 10:25)

The point of Christ's atonement, completed in his resurrection, is that we too may be raised from spiritual death as well as physical death.

Alma, also in the Book of Mormon, preaches a beautiful sermon on the atonement, and in it he explains what this new physical and spiritual life entails by explaining what Jesus did:

He shall go forth,

suffering pains and afflictions and temptations of every kind --

and this that the word might be fulfilled which saith: He will take upon him the pains and the sicknesses of his people.

And he will take upon him death,

that he may loose the bands of death which bind his people.

And he will take upon him their infirmities,

that his bowels may be filled with mercy according to the flesh,

that he may know according to the flesh

how to succor his people according to their infirmities. (Alma 7:11-12;formatted according toThe Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text)

Unity with God, atonement, comes because God has condescended to be one of us (1 Ne. 11:16-21). He too can be affected. He too can be made to weep (Jn. 11:35; Moses 7:28).

Jesus emphasized the physicality of his resurrection in his appearances: "Handle me and see," he said to his first Apostles (Lk. 24:39). He had Thomas, who had not been with the disciples at the Lord's first appearance, put his finger into the Lord's wounds (Jn. 20:27) and he commanded the Nephites who witnessed his appearance in the New World to do the same thing (3 Ne. 11:13-16). That he, too, could be touched, whether in a wound or with affection, was crucial to his appearance.