Twenty years ago a man twice my age leaned across a conference room table, wagging his finger in my face. He was flanked by his colleagues—all of them ordained.

"Young man, if you think you are going to go away and get a doctoral degree and then come back and take First Church, you're mistaken. You will go to Gravel Switch, just like everyone else."

It was my first taste of realpolitik. I was young, idealistic, and I saw the business of getting a doctoral degree simply as a matter of equipping myself to offer the church every gift I could develop.

I was also shocked to discover that the people in "Gravel Switch" were used as a means of blunting my ambition. From my point of view the people who lived there—presumably countless small rural churches—were every bit as deserving of well-qualified clergy as anyone else.

I went on to do my degree and I did find myself in Gravel Switch. The doctoral degree also proved to be an issue, over and over again.

Years later and a denominational world apart, I know that the same attitudes and behaviors are "out there"—across the denominational landscape. I hear it in the stories that students and clergy tell me. Some of them are patiently waiting for someone to recognize their gifts. Some of them are wasting away, doing jobs that are alien to them. Some are deeply bitter. And others have moved on to tasks elsewhere in the church, paying lip service to the system, while quietly evading the punitive nature of deployment schemes that never acknowledged or used their gifts.

The problem could be evaluated in bureaucratic terms. It could be chalked up to time and attention. Or we could just use the language of "human resources." But in truth it is also a spiritual and moral question. When the church fails to weigh vocations in a prayerful, intentional fashion—when gaming and one-upmanship dominate—when people are hazed for membership in the club—we model a way of life that is deeply at odds with our baptismal commitment to honor all persons.

This does not mean that everyone who seeks ordination, or who insists that they have this or that gift should be ordained or given the task that they imagine should be theirs. In spite of differences in polity every denomination holds that ordination is discerned in community. Furthermore, ordination is not a "right" to be claimed. It is a vocation—among many—to which some are called and others are not.

But when those theological tenets are used to mask corporate behavior that is shaped by envy or a simple lack of imagination, we betray just how fragile our preaching to others can be about the moral and spiritual dimensions of work. If the church is not capable of functioning differently, how can we possibly expect the companies of the work-a-day world to be any different? How much of what we say on Sunday can we expect the people in church pews to apply to their lives on Monday morning, if life in the church is fraught with the same corporate dynamics that up-end the lives of people who work on Main Street? And what do we communicate about our understanding of lives and our love of one another when the politics of church life are just as "dirty" as the politics of any other organization?

I don't want to be a Pollyanna about this. Karl Rahner once observed that sin in the church is inevitable, because the church is filled with sinners. Mistakes will be made. Christians will injure one another in the course of their work together and the limits of human strength and attention will fray at the edges.

But we are still a long way from having given enough attention to the everyday task of discernment to claim that only a few errors in judgment arise from time to time. And, on balance, we have yet to scratch the surface in helping not only potential clergy, but the whole of the church in discerning or using its gifts.

When bishops, district superintendents, deployment officers—as well as the clergy of dioceses, conferences, and synods --begin to move the task of vocational discernment to the forefront of what they do, then the people in the pews might have better reason to take their admonitions about the work world more seriously. And when the church begins to take seriously the task of helping all of God's people to discern the nature of their gifts, then those who are "spiritual, but not religious" might begin to sense the connection between some of what happens on Sunday and the work to be done on Monday.

Because of what I believe about the value of all God's people, I no longer think of "Gravel Switch" as a particular kind of church in a particular location. I think of it as a metaphor for the message, "We aren't paying attention—because we have our own agenda, or because we don't care, or because we are trying to protect our turf—and you are going to suffer for it, because we will bury your gifts."

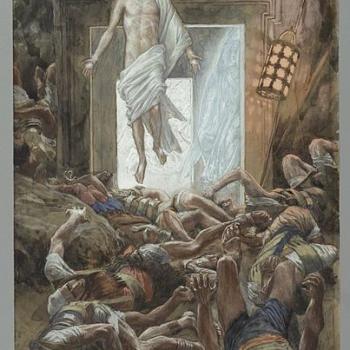

There are parables in the Gospels about that kind of behavior. And it is worth measuring the spiritual implications.

9/16/2012 4:00:00 AM