Lectionary Reflections

Acts 2:14a, 22-32

April 27, 2014

As has been common for centuries, the lectionary collectors turn to the book of the Acts after Easter to trace the movement of the early Christian communities from the Jerusalem temple to the "ends of the earth," which in those times meant the city of Rome. It is hardly an accident that Acts ends with Paul preaching openly in the capital city of the empire.

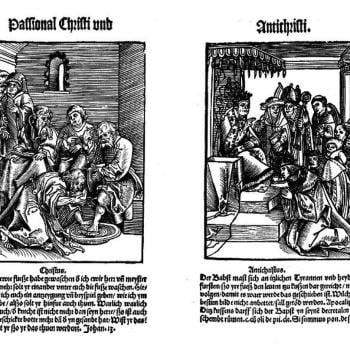

It is always important to remember that in Luke's gospel, the first volume of his two-volume work, one of his chief goals was to insist that the expected parousia, the supposedly imminent return of Jesus in glory and power (cf. Mark 9:1 for a classic portrait of that hope), was delayed with little real certainty that it was going to occur soon. Hence, Luke goes about describing a church that must find its way in a Roman world, as well as a world where the traditional Jewish believers have refused to recognize Jesus as the long-awaited Messiah of Judaism. As a result of this basic conviction, Luke goes out of his way, at least in part, to exonerate the Romans of the death of Jesus, and deeply to implicate the Jewish authorities in that death. For example, in Luke 23 where Jesus stands before the Roman governor, Pilate, three times Luke has Pilate say that he finds Jesus innocent of any crimes worthy of death. In contrast, we learn from Josephus that Pilate was so monstrous as governor that the Romans themselves deposed him from that office! It is less than likely that the Pilate of history would have found the rabble-rouser Jesus guiltless; he rather would have had him tortured and killed forthwith as a threat to Roman power. But, for Luke, it is the Jewish leaders who are finally responsible.

It is tragic, and ultimately horrifying, that this scenario has wormed its way right into the heart of the Christian message as it was preached in the earliest church. And that particular understanding of the relationship between Jews and Christians has continued right up until our own time. We must never forget that it was not until the 1960s, only about fifty years ago, that the Roman Catholic Church finally removed from its doctrinal understanding of the Christian/Jewish relationship that the Jews were "Christ killers." It cannot be denied that at least part of that demonic notion arose from this Petrine sermon on the day of Pentecost.

Before we look with a bit more care at the contents of this sermon, it is well to state one fact clearly: the conflict here is not Jew against Christian. The conflict is one between Jew and Jew. Nearly all those who heard Peter that day, at least in Luke's retelling of it, were Jewish. Why else would Peter say at Acts 2:29 when addressing his listeners, "brothers," implying that he is an Israelite just as they are. The struggle here is an inner Jewish one, revolving around the proper understanding of just who Jesus is: prophet or Messiah. It will not be long, of course, perhaps less than a decade after Luke writes his works, that a complete break between traditional Judaism and emergent Christianity will at last occur (this break may be signaled for us in John 9 and the story of the man born blind).

Peter's sermon sets the tone and shape of the earliest Christian preaching. In fact, some scholars suggest that Luke was the pioneer of such preaching, while others say that he was ringing changes on a preaching that was already several decades old as he wrote. Whichever is the historical answer to this chicken/egg debate, the influence of this sermon on the future of Christian theology and practice, especially with regard to the Jews, both for good and for bad, is incalculable.

Peter begins by saying to the assembled Jewish authorities that Jesus was "attested to you by God" (Acts 2:22). The Greek verb, translated in the NRSV "attest," can also mean "display" or "appoint." Peter states here quite directly that the coming of Jesus was nothing less than God's determined act, both to show Jesus as a prophet of Israel, but also to demonstrate through his mighty acts that he was far more than prophet. He was in fact God's Messiah. Luke has already made such a demonstration of Jesus' messianic status in his very first sermon in his hometown of Nazareth (Lk. 4). There he reads the clearly messianic passage from Isaiah 61 and claims that the text has "today been fulfilled in their hearing." The assembled congregation welcomes such golden promises from a local boy made good, but after Jesus goes on to accuse the hearers of misreading their own tradition about to whom the message should be given, the crowd turns ugly and tries to kill Jesus by hurling him off a nearby cliff. That threat, Peter says next, has now been completed by the Jewish authorities who are listening to him in Jerusalem.

Acts 2:23 is fairly crammed with dangerous language, a language that has caused no end of horrors in the world until our own day. "This man, who was delivered up by the set plan and foreknowledge of God, you killed by crucifixion through the hands of lawless people." Peter first claims that the entire scenario of Jesus' passion, his false arrest, his torture, his mockery, his agonizing death, were all the exact plan of God. This idea has lead theologians of all stripes a merry chase down through the ages. If it is not a statement of predestination, it is hard to imagine what such a statement might look like. To that Peter adds the direct accusation that "you killed (him) by crucifixion." Peter acts here as judge and jury, shouting to the assembled Jewish leaders that they are without doubt the murderers of Christ, their own Messiah. Exactly how we are to hear the clause that follows: "through the hands of lawless people" is not quite clear, but the murder charge is not undercut by the clause in any way. The Jews are murderers!