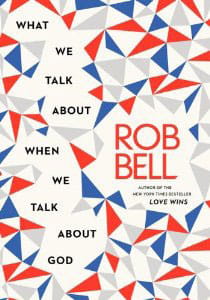

On the kickoff date for Rob Bell's new book, What We Talk About When We Talk About God the hosts of MSNBC's Morning Joe asked Bell whether he was intentionally trying to "rebrand God." Bell—who had also visited the show in March 2011 in the wake of Love Wins—seemed quite comfortable and answered the question with his usual aplomb. He knows how the media works, and he uses that knowledge very well. Bell, as I explained in my recent book Rob Bell and a New American Christianity, uses his genius to repaint the faith. During, and perhaps as a result of, his continual efforts to reinvigorate American Christianity, Bell has morphed from a colorful and powerful conservative Christian to a new type of believer that refuses labels—but is clearly distant from his early evangelical roots. He sees himself following in Jesus' footsteps, refashioning—and in some ways updating—the faith to attract new followers, even as some attack his work.

Bell's book does and will speak to many audiences. He continues to assert both that the universe is open and that, as the Congregationalists like to say, "God is still speaking." The God of Christian faith has the power to act, to forgive, to reconcile, and to empower people to conceive of and to act out deeds of courage, love, and justice.

Bell is, himself, a poignant example of a central Christian narrative: that God is with us not just in our success but even more stunningly in our failure. Bell has always argued that when Jesus says, "Blessed are the poor," he means it literally. That is, the blessedness that Jesus talks about is a radical "with-ness" in our mourning, in our struggles, and in our despair. Grace, as unconditional favor, is the good news precisely because it reaches us in our depths. And, for Bell, not only is God with us in Christ, but God is "for" us. God therefore is the great "de-escalator." That is, in Christ, revenge ends. Scapegoating is off limits. We let go of bullying and turn toward each other in a "for-ness" that transforms us.

Bell goes on to show that scripture—both in its own context and even in our time—demonstrates a multiplicity of ways that God is "ahead" of us. The Bible makes a break from "tribal-consciousness," by arguing that God is not in one place and at one time, but in all places and all at once. This God, whose center is everywhere, does not pick favorites, and neither should we. In this sense, the "ahead-of-ness" of God is always moving beyond our parochial boundaries and attitudes toward a place of final reconciliation, where all of God's children are found, loved, and embraced. In this way, the beauty of Bell's faith is one that rings true not only for Christians, whether conservative or liberal, but also non-Christians; for Bell, we are all one family in Christ. And this is good news.

While I think this book will be life giving to many, nothing here is really new for Bell. He has been repainting the faith for at least a decade—and in more or less the same way.

On the other hand, I think Bell is up to something even more ambitious than presenting his generous view of Christian orthodoxy. What We Talk About When We Talk About God is an attempt to suggest that the universe is much "weirder" than most of us think, and in that sense, much more indeterminate and open than our common sense might otherwise tell us. Our mistake is to believe that what we think about the world necessarily reflects the very nature of God. If our worldview is pinched by either rationalism that limits God (read, liberals), or by a self-righteousness that makes God a kind of bully (read, conservatives) than we mistake our own perceptions for the reality of God's very nature.

On the other hand, I think Bell is up to something even more ambitious than presenting his generous view of Christian orthodoxy. What We Talk About When We Talk About God is an attempt to suggest that the universe is much "weirder" than most of us think, and in that sense, much more indeterminate and open than our common sense might otherwise tell us. Our mistake is to believe that what we think about the world necessarily reflects the very nature of God. If our worldview is pinched by either rationalism that limits God (read, liberals), or by a self-righteousness that makes God a kind of bully (read, conservatives) than we mistake our own perceptions for the reality of God's very nature.

This deals precisely with the question that thinkers and theologians have struggled with for the last two centuries: "Is God really only a projection of whatever subjectivity that is being imagined?" And if so, is this a projection that alienates one from our best selves, as Marx averred and Feuerbach echoed? Or, is God merely a name for our social group feelings, as Durkheim proposed? Or an infantile fantasy, as Freud deduced? Many have wondered about these questions.

At this point, we are a long way from the evangelicalism of Bell's past or the kind of biblically centered God of present day evangelical Christians. Bell is suggesting, by summarizing modern discoveries in physics in pithy and popular ways, that the universe is much "weirder" than we are able to fathom, and that this "weirdness" must lead to a kind of distrust of certainty and more importantly to an openness to surprises.