The Occupy movement has already caught some of the bounty that faith-based organizing has to offer. Before and especially after last fall's wave of evictions, Occupiers have met, slept, and eaten in houses of worship. Religious communities possess tremendous quantities of real estate, no small amount of it unused. Such spaces could become available to the movement, and by means more diplomatic than the failed, forced occupations of church property tried in New York and, most recently, San Francisco. Far preferable, I would think, are Occupiers' successes in defending from closure an historic black church in Atlanta and a Catholic homeless center in Providence.

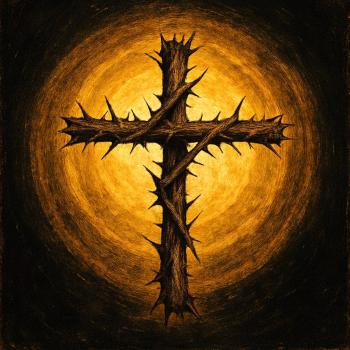

Meanwhile, for a movement that has still failed to bring eviction-defense and anti-foreclosure action to a mass scale, religious groups provide the ideal platform for doing so; equip them with the right tools and strategies, and when some of their own are threatened by the banks, their fellow faithful will rally to save their homes-not merely on the basis of political ideology, but with the far more powerful motivation of looking out for the community. This kind of action also has special resonance in religious traditions, from the debt-forgiving Jubilee of the Hebrew scriptures, to the radical aid for those in need taught and practiced by Jesus Christ, to the ban on usury in Islamic law. An act may be civil disobedience by temporal standards, but to a higher law, resisting oppression is a basic requirement.

One need only think of the civil rights movement, arguably the last mass resistance movement in the U.S. to win decisive political gains. In it, churches were often the basic units of organizing. Clergy locked arms with activists at the front lines, and together they won.

The tryst between civil rights and churches, however, was not always a happy one. Southern clergy, both black and white, had learned to benefit from segregation, and a new civil rights organizer in town could represent a threat to their privileges. Saul Alinsky claimed that he never got anywhere appealing to clergy by the precepts of their faith. "Instead," he wrote, "I approach them on the basis of their own self-interest, the welfare of their Church, even its physical property." An eminent religion reporter I know says he deals with them like he used to deal with the mob. The clergy-driven Occupy Faith network has been created to be an interface between the leaderless movement and the needs of professional religious leaders. It's not an easy task, Occupy Faith's organizers realize, but it needs to be done. The alliance between churches and civil rights ultimately worked because courageous people made clear that it had to.

While most religious communities don't come anywhere near the Occupy standard for horizontality and transparency--nor does Occupy, for that matter--they're not as bad as an outsider might think. The flock often finds plenty of ways of scaring the shepherd-from the power of the pocketbook, to steering committees and boards, to the threat of simply picking up and going elsewhere. That's why, as with unions, Occupy isn't going to get anywhere with religious communities until it wins over the rank-and-file. Then, leaders will have to show support for the movement, or else.

As I stood waiting for the action against Trinity Church to begin on December 17, I struck up a conversation with a man in a Roman collar and a black beret, Fr. Paul Mayer--a formerly married Catholic priest and veteran of every major American social justice movement since he marched with Martin Luther King, Jr., in the 1960s. Trinity is an Episcopal church; I asked him what he thought Catholics would do if OWS were making a demand like this of us.

"We'd be worse," he replied.

I didn't know it at the time, but, together with Episcopal Bishop George Packard and Sr. Susan Wilcox, a Catholic nun, Mayer was about to lead the charge over the fence, down onto Trinity property, and promptly into police custody. The following night, out of jail, he and Wilcox joined me and a lapsed cradle Catholic, a theologian, and a sociology student for the first meeting of Occupy Catholics at a bar near Zuccotti Park. We came together with a common but still not quite clarified desire to create an affinity group of Catholics involved with the movement, as well as to take what the movement was teaching us and bring it to our church. Maybe, someday, we could help Catholic churches respond better to Occupiers than Trinity did, and vise versa.

So far our emphasis has been on reaching out to laypeople, online and through the social justice ministries of nearby churches. We've held a general assembly at Maryhouse Catholic Worker, part of the organization Dorothy Day co-founded with Christian anarchist principles to serve the poor and struggle for justice and peace. For months we've been slowly growing, planning, and praying about how to lead our church, the biggest landowner in New York City, to join Occupy's call for a more righteous society. We've been teaching Catholics about the movement and Occupiers about the long and deep Catholic social justice tradition. We got this group going because the connection between Occupy and our faith was so obvious we couldn't ignore it. We needed this movement, and we know that the movement no less needs us.

This past Good Friday, the most solemn day of the Christian year, we stood in front of St. Patrick's Cathedral and sang, "Were you there when they crucified the poor?" against the bishops' silence on a budget in Congress poised to slash services upon which the 99 percent depends. "We love our church," we cried with the people's mic, "and right now the church needs to speak." So we did. Maybe next time we go to St. Patrick's, we'll be sleeping on the sidewalk.