“Religion Behind the Scenes” spotlights the less discussed, but no less crucial, tasks that keep religious communities running, and the people who make it all happen.

As a young boy, I remember watching each week the popular series, Kung Fu. The opening credits showed what appeared to be Chan Buddhist monks, clad in pajama-like robes, sporting shaved heads, ceaselessly practicing martial arts. Only later would I realize that the show had not only fictionalized the martial arts depicted therein, but also grossly misrepresented the life of Buddhist monks.

Westerners seldom genuinely understand Buddhism—and most of us, at some point, have been introduced to some caricature of Buddhism, which ends up getting solidified in our minds as an accurate depiction of what that religion is like, what practitioners believe, and what monasticism consists of.

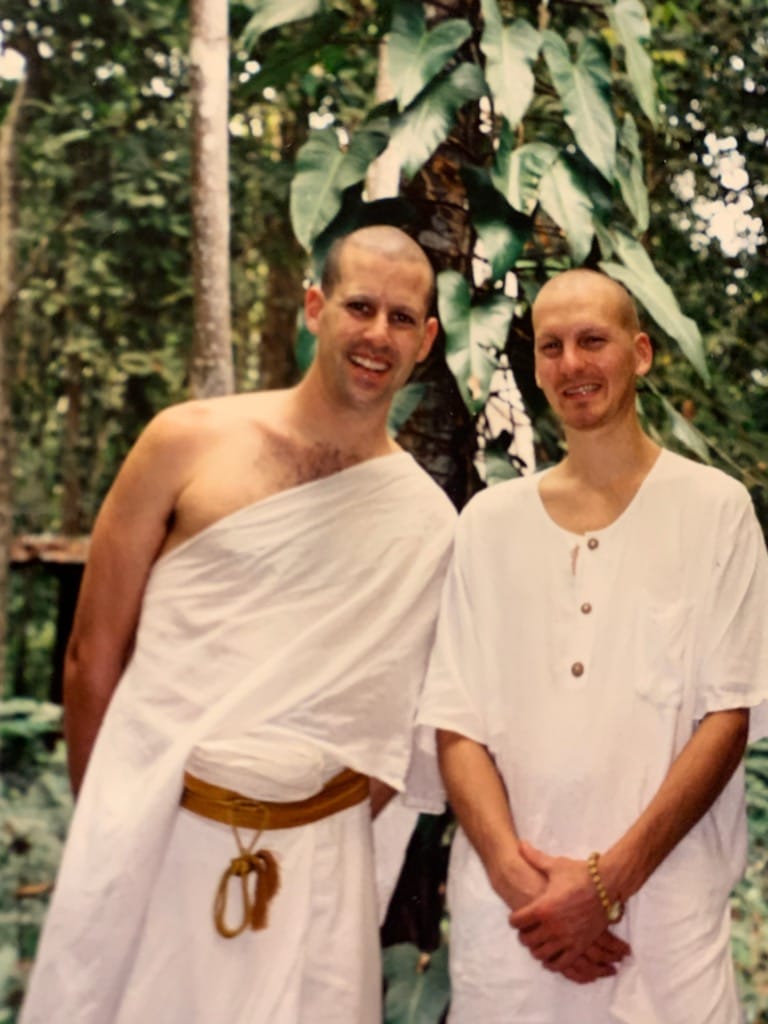

In this installment of Religion Behind the Scenes, I’ll introduce you to Bhante Subhūti, a Buddhist monk living in Myanmar, whose personal blog (“American Monk”) chronicles not only his personal journey as a monastic, but which also shares insights into Buddhism, life, people, and the world around us. Among other things, in our interview we discussed Buddhist monastic robes, how they’re made and used, and that they mean to those who wear them.

So, I am assuming you are a Theravāda Buddhist Monk. Is that correct?

Yeah, I am. Theravāda is the Buddhism that is in Myanmar, where I live. It’s the most common form of Buddhism in Myanmar, but it is also common in Thailand, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, and Laos.

Theravāda (as articulated in the ancient Pali texts) is considered the oldest version of Buddhism—the closest to what the Buddha actually taught. Of course, there are different sects in Theravāda Buddhism.

Are you a convert to Buddhism?

Oh, yeah. My parents were Jewish. I was raised a secular Jew. I had the bar mitzvah, as thirteen-year-old boys usually do. I don't even remember what I recited during my bar mitzvah. I was just culturally Jewish. I think a lot of Jewish people admit to being culturally Jewish, rather than actually religiously Jewish.

I never actually believed in God—except if I was in trouble or something. I remember, as a little kid, telling the rabbi “I don't believe in God.”

So how did you get into Buddhism?

I got into Buddhism during my freshman year at Central Connecticut State University. Your first semester there, you aren’t allowed to pre-select your classes. You have to go through the add/drop process for each class. Only after your first semester can you pre-register for classes you want to take. So, your first semester is just crazy, and you end up taking whatever you can get into. And one of the classes I was able to get into happened to be a world religions class. That turned out to be interesting to me. I was a vegetarian, and I didn't drink, didn't party or anything like that. And in that class I learned about Buddhism. And I was like, “Hey! I sort of resonate with this stuff. I like this.” So, I had a friend who knew a bit about Zen Buddhism—which is really focused on meditation. So I asked him to teach me how to meditate. And I just stuck with it. And then later I identified as being Buddhist.

Okay, so how did you got from being a practitioner of Buddhism to becoming a Buddhist monk?

I was going to be a teacher, but I went into computer programming instead and made a lot of money very quickly. I was told as a child that money would always serve as a solution for life. My grandmother even had a humorous plaque on her kitchen windowsill that said, “Money isn’t everything, but it sure beats second place.” However, after I was able to make a lot of money, I realized that money wasn’t important to me. I was still the same person.

I found myself getting more and more serious about Buddhism—getting more into it. The more I read the Suttas, the more I desired the monastic life. I felt this need to become a monk—and to do this fulltime. So, I asked my parents if I could become a monk at this Mahayana monastery, and they said, “No!” (You had to have your parent’s permission to join the monastery.)

I worked for Bayer for a while. They had this human blood analyzer project I worked on. But phase 2 was set for multi-species, and would be used to test blood from lab animals, such as lab rats. I was an animal rights person, so I couldn’t bring myself to work on it. So, that served as a catalyst for me to buy a plane ticket and give my notice. I had lofty plans of visiting monasteries and meditation centers around the world but ended up in Hawaii instead, living on the beach, playing my guitar. I stopped meditating and started losing my path.

And then I went to Fiji. And while in Fiji, I was in the ocean showing these two travelers how to play “Shark Attack.” A few hours later, I looked at my wrist and noticed my watch was missing. I had apparently lost it while playing “Shark Attack.” I immediately got some snorkel gear and started searching. It was not to be found. When it was low tide, I decided to take another look. Still no watch. I told some Fijian kids I would give them lots of money if they found it. They looked around for a few minutes and gave up, thinking it was silly to look for a watch after it had been lost in the ocean for four or five hours. Losing the watch was quite symbolic for me since it was most useful for waking up early at the monasteries and timing my meditations with its countdown timer. The frequency of meditation sessions during my trip had quickly dwindled, and so did my Buddhist path. Losing my watch was a big message for me. I wondered if it was possible to recover what I had lost; and I don’t mean the watch! I had trouble sleeping that night. I happened to wake up as the sun was starting to rise. As I was walking on the beach, I thought to myself, “I wonder if I can find my watch this morning?” As I approached the shore, I thought about how impossible it would be to find a watch lost in the ocean for basically 24-hours. I said to myself, “If I find my watch, I will definitely become a monk! No more games—I will really do it.” Almost immediately after I said that to myself, in the distance I could see something flip-flopping as the calm morning ocean waves lapped the shore’s edge. As I walked closer, I saw that it was the black Velcro strap of my watch floating with the face half-buried in the sand. I hesitated for a moment, smiled, and felt something like a defeat or possibly a surrender. There were no more games I could play to hold myself back from being ordained. Standing in front of my watch, I thought of the impossible “If I find my watch…” promise I’d made, which I thought I would never be held accountable for. Nobody would ever know if I just kept on walking, but finding the watch was just too much of a coincidence to let this moment of truth simply drift away. I lowered myself down to pick up the watch. I had to be true to who I was, or what I was to become. As I picked it up, I felt it was one of the heaviest things I had ever picked up. Change and destiny, especially my own, bore a lot of weight. After this, the only question was when I would become a monk, and that was only a matter of time.

I have a follow-up question to something you said earlier. You mentioned that when you were Jewish, you didn't believe in God. You’re a Theravāda Buddhist now, so I assume you still don’t believe in God—as most Theravāda Buddhists don’t. Is that accurate?

You’re correct. I don't believe in “God.” We believe in “gods” in Theravāda Buddhism; but they aren’t gods in the sense that Christians use that term. They’re what we call “devas” or “heavenly beings.” They have god-like characteristics but they aren’t creators or deities. We don’t believe in anything like the Western idea of God. When Christians asked me if I believe in a “Creator,” I tell them that “I believe that karma is my Creator.”

Let’s turn our attention to the robes you wear. Why do Buddhist monastics wear robes instead of secular clothing—as lay Buddhists do?

Well, I'm not sure what lay people wore 2,600 years ago, but I think they may have worn robes as well. It’s like in India, you know? The ladies wear saris there.

The main reason we wear robes is “the fewness of wishes” principle. We are ascetics and non-greed (or “fewness of wishes”) is one of the traditional ascetic practices. We need to be non-possessive, not greedy. So, the four “requisites” are robes, food, lodging, and medicine. Nothing more is requisite or necessary for the monastic life. We should pursue a simple life and desire just what we have now—but nothing more. Monks were supposed to only have three robes during the time of the Buddha. That emphasized the idea of a simple life. Few possessions and fewness of wishes makes the monks easier to support.

Additionally, today, the robes are also a part of our identity. It’s kind of like our “uniform.” It brands us, so that we’re recognizable. You know someone is a monk when you see them, mostly because of how we dress, but because of other things too.

In wearing robes and shaving our heads, we also lose our individuality, which is so very important. Unique hairstyles create individual identities, as do clothing styles. But, by rejecting those, we become one. Individuality is lost.

As I understand it, monks used to be called “rag-robe wearers” because their robes had to be made by hand from discarded rags. Since that’s not the requirement anymore, where do most monks get their robes? Do they make them? Purchase them?

They can be made or purchased. We actually get robes donated to us a few times a year. We have generous donors who want to make sure we have what we need. It was very difficult to get cotton robes a long time ago, when I was first ordained. Our teacher arranged for us to be able to get cotton robes. There is a donor in Singapore who has a factory, and he started making robes for us. There are many companies that make them according to different Buddhist traditions and specifications. Actually, most commercially manufactured robes are not manufactured in a way that makes them allowable for us to wear, based on monastic rules. For example, some of the pieces must be cut and then sewed together. This is especially true with the robe’s borders. But some manufacturers want to just fold the fabric and sew it—creating a fake seam—because that reduces the time it takes to make the robe by about 1/3. But it actually renders the robe unusable.

If you’re going to make them yourself, there are different rules about robes and how they should be made. For example, “rag robe” wearers can use a machine to sew the pieces together, but the “rags” must be discarded pieces of cloth. Lay donors usually offer pre-made robes or they offer reams of cloth (white or dyed) and we make the robes ourselves from that cloth—and dye them ourselves or put a coating of natural dye on top of a pre-dyed fabric.

Can you tell us a bit about how monastic robes are made?

Well, we're mendicants, we're begging monks, okay? And we're supposed to have this ascetic ideal. So originally, large pieces of cloth were hard to come by. Even today, a bolt of fabric is usually only like 42 inches wide. So, what they did anciently was they took small pieces of cloth—often ripped clothing that they had found in the rubbish heap—and they would take the salvageable parts and stitch them together to make robes for themselves.

They didn’t have our modern dyeing techniques, so they probably only had solid colors, and the colors were probably not very strong or vibrant—because they obviously only had colors they could make out of berries, bark, and things like that. So, the robes were in colors like a drab maroon or brown.

As for the pattern of our robes, the Buddha was walking near a paddy field one day, and he said to Ānanda, “Oh, this pattern is beautiful. All robes should look like this.” And so, that is the pattern of Theravāda monastic robes today. The pieces of cloth are sewn together so that they look just like a rectangular rice paddy field.

I read on your blog about how you’ve repaired robes. Have you ever actually made a set of robes from scratch yourself?

Yeah, I actually made a robe by hand, stitching it without a sewing machine. I made it this way because the sewing machines are often broken. Later, I was interested in how long it would actually take to make one by hand. It took me 150 hours to make a lower robe and upper robe. At an hour a day, it takes about five months to make robes.

How have Buddhist monastic robes changed over time?

Well, Theravāda monks don't have tubular components to our robes—like sleeves for the arms or leggings for the legs. And that’s how the robes would have been in the Buddha’s day. The Mahayana robes (of China), on the other hand, are more like pajamas. Theirs have evolved. So, monks in the Ajahn Chah tradition, for example, do a lot of work, which is more like the Christian monastic ideal—like the Trappist monks. Well, it's not very easy to work in robes, because they just fall off. (You may have noticed that, even while I’ve been talking with you, I keep adjusting my robe because it keeps falling off my shoulder—because it’s just a piece of loose cloth.) So, if you’re working in the traditional Theravāda robes, either the robes sort of fly around you, or they fall off, and their just not very conducive to doing manual labor projects. For instance, in the Ajahn Chah tradition, they’ve changed the monastic dress so that they can do the kind of work they need to without being hindered by their robes. Perhaps that’s the same progression or evolution that Mahayana robes have gone through.

You wear maroon robes. I’ve noticed Vajrayana (or Tibetan) monks wearing gold and maroon together. I’ve seen Buddhist monks in tan or grey robes. What determines the look, style, and color of monastic robes? The denomination? The nation? The monastery or community they are affiliated with?

Well, within the Mahayana, Vajrayana, and Theravāda traditions, they each have a certain style of robes. While the style is pretty consistent in a given denomination, the color can change. The color varies from group to group and country to country. So, Thích Nhất Hạnh, for example, his monks wear a brownish type of robe. They strayed away from the bluish-gray robe which was quite standard in Thiền Buddhism—which is a branch of Zen Buddhism (in the Mahayana tradition).

Now, monks in the same tradition might wear the same robe in different ways. So, for example, we have a rule that upper robe should be four fingers from the bottom of the kneecap. And the lower robe should be eight fingers from the bottom of the kneecap. That way, you'll see two layers. So, we have a “dress code” we’re supposed to follow. Though, in Burma—just about everywhere—there’s a casualness about wearing the robes properly. The monks who have their arms exposed when out in the village, especially the right shoulder—these are monks that don't follow the rules. So, that variety of how various monks obey the rules probably exists in other Buddhist traditions as well.

As a Theravāda monk, you wear three robes, correct? What can you tell us about those?

So, there are three robes. If you can imagine a twin-size bedsheet, that would be the lower robe. The upper robes would be more like a queen or king-sized sheet. The lower robe is functionally your underwear. The upper robe is what is visible when a monk is out in public. And then there's a double robe, which is a double-layered robe—worn largely in colder weather. It depends on where you live, but I live in the mountains where it's quite chilly. So, I'll take my third robe, and I'll wrap it around me like shawl.

At one point, the Buddha saw people walking on the road, and they had like 20 robes, and he was like, “What is this? My monks are walking with mattresses on their backs.” That's what he said. And he's like, “How many robes does one need?” He stayed up one night, with only one robe on. He was cold, so he put on a second robe and—around the “third watch” of the night—he was still cold, so he put on a third robe. Then he was adequately warm, and so he determined that three robes were sufficient for monks to have and wear. (See Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Buddhist Monastic Code 1:143)

What are aspects of the making or wearing of monastic robes that might surprise some people?

As I mentioned, in the Theravāda tradition, our robes aren’t tubular—with sleeves or leggings. So, you can actually go quite a long time without washing your clothes, because they just hang on your body. I'll wear my robes every day, but I wash my lower robe about twice a week, and my upper robe only gets washed maybe once or twice a month, or as needed. That might surprise some. I hope I will never have to wear lay clothes again, not even underwear. I've gotten so used to wearing robes, I love robes. They're just part of my identity. And it's part of my rejection of the regular life. I do wear socks though when it is cold.

Are there any “taboos” about monastic robes that people should be aware of?

One definitely should not wear monastic robes unless he or she is actually a monk. This is very important. Like, it might be “cool” to go to a costume party or dress up as a monk for Halloween, but it's considered a really bad thing to do—mostly if you’re really pretending to be a monk and getting gains from this. In a case like that, it is like stealing from the reputation of monks—and that’s considered really bad.

So, if you want dress up for Halloween as an ascetic, use a white or blue bedsheet—so that you’re not actually wearing monastic robes. And, instead of saying that you’re a “bhikkhu” or ordained monk, wear a white sheet and say that you’re an un-ordained “ascetic” or going to a “toga party,” or something like that. But dressing up as an ordained monk really isn’t appropriate.

Do you have an unusual story related to wearing monastic robes?

One time, someone asked me if I would wear some robes in honor of his father’s three-month death anniversary. I didn’t think much about it and agreed to do so. A week or so later, he came with a set of robes, and said to me, “These robes were spread over my father at his funeral.” Can you imagine agreeing to wear robes in honor of someone’s deceased father, and then finding out later that means you would be wearing something laid over him after he was dead? It was awkward, but a promise is a promise. Normally, a cloth that is placed over a dead body is discarded before burning the body—and nobody wants that cloth. If a Monk takes that cloth (after it has been discarded), he would boil and sterilize it before using it. I didn't have any facilities to boil the robe spread over the deceased father, so I just washed it with a lot of detergent—and I washed it twice! Funny, but it was actually a very nice robe, and I grew to really like it.

Has wearing monastic robes affected you spiritually in any way?

Well, when you’re ordained, you become sort of like a child. You have to learn how to eat again and how to dress again (because there are rules for all of these things). If you need something, you have to ask someone to give it to you—because you don’t touch money. This is another thing that puts us into a childlike and innocent way of life. And so, the robes kind of tell us what we are supposed to be doing. We’re supposed to behave and act in a certain way. They remind us of our simple life; of our separation from our previous life (before we were ordained). They’re our uniform. They help protect you because they’re a signal to other people that we're different; we’re part of a celebrate order, you know? So, maybe they’re a female repellent as well.

Is there anything else that you would want our readers to know about your experience as a monastic, wearing these robes, or living the life of a monk?

You said you wanted the “Behind the Scenes” information. Your question reminds me of a story I wrote, called “Walkman Karaoke.” Many years ago, in Greenwich, Connecticut, I frequently encountered a young man with Down’s syndrome. He would be walking up and down the sidewalks with the headphones of his Walkman portable cassette player at full blast. He would sing just about as loud as the music playing in his ears. It was very annoying and quite out of place for Greenwich, but it was quite clear that he was happy singing and not really caring about the world outside. He was in another world, a world that others could not hear. To him, the music mixed with his own voice and sounded as sweet as honey. Maybe, if we all could hear the music he was hearing, he might not sound so bad. We’ve all done this before—singing along with our headphones, until we learned how funny it sounded to others. If he was in front of a karaoke setup, he might actually sound good! But he was alone in his own experience, immersed in the world of “Walkman Karaoke.” He was like a performer who is the only one who can hear his voice together with the musical accompaniment. The performer might sound terrible to the audience, but not to himself. In the same way, I am inside this monastery, and you are outside. I am the performer immersed in this monastic world, while all you know are words from these stories I’ve shared. In other words, most of you probably don’t have any idea what Theravāda Buddhism is, let alone what it is like to be a monk in this tradition. I realize this and wish to draw you deeper into the world that I perceive. I may not seem much different than a Walkman karaoke performer. In this conversation, I’ve let you hear a bit of the music playing in my headphones. I’ve tried to give you a good look inside, to let you in on some of the behind-the-scenes action. Hopefully, you can hear a bit of the music I hear and see the beauty of the life I live… as a robe wearing Buddhist monk!

Interview conducted, transcribed, edited, and condensed by Alonzo L. Gaskill.

Learn more about Buddhism and the world's religions in Patheos's Library.11/1/2024 7:59:59 PM