“Religion Behind the Scenes” spotlights the less discussed, but no less crucial, tasks that keep religious communities running, and the people who make it all happen.

In the Jewish scriptural canon, God commanded Moses: “Speak to the Israelites and say to them: ‘Throughout the generations to come you are to make tassels on the corners of your garments, with a blue cord on each tassel. You will have these tassels to look at and so you will remember all the commands of the Lord, that you may obey them and not prostitute yourselves by chasing after the lusts of your own hearts and eyes.’” (Numbers 15:38-39) Based on this ancient commandment (or “mitzvah”), observant Jews today will wear a prayer shawl (or “tallit”) and/or an undershirt (called a “tallit katan”) which has knotted tassels (or “tzitzit”) on each of the four corners. In the Orthodox strands of Judaism, this shawl or garment is worn by men when reading from the Torah, saying prayers, participating in synagogue services, at one’s bar mitzvah or wedding, on the High Holy Days, etc. In some of the more progressive Jewish denominations, both men and women will wear a prayer shawl—particularly during synagogue services, but less commonly in the other aforementioned settings.

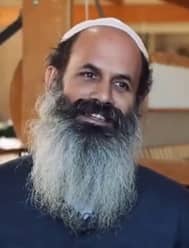

Ori Faran (of tallis-man.com) is a weaver who, for the last 17 years, has created handmade, personally designed prayer shawls which enable observant Jews to keep this commandment. In this Religion Behind the Scenes interview, Ori tells us a bit about how he got into this sacred work, how he makes tallitot (or prayer shawls), and what they mean to practicing Jews who wear them.

Have you always been religious? And, if so, what denomination of Judaism do you identify with?

Well, I grew up in a secular Kibbutz in Israel. It was Jewish but didn’t observe anything religious. I think it was anti-religious, really. But, after my stint in the army—having spent time in various places around the world, (like India and Europe)—I started my spiritual journey and slowly became religious. I suppose “Orthodox” is the best way to describe my personal leanings, but I don’t like to define myself by any labels like that.

All my life I believed in God; I knew there was a God. I remember, as a child, I would speak to God. And as a teenager, I had a group of friends who were, themselves, on a spiritual journey, thinking about it, talking about it, but not really in the Jewish sense of spirituality or religion. After the army, my older brother became religious, and that kind of opened the door for me, and I started getting more engaged in Judaism as a result.

Could you briefly explain (for our non-Jewish readers) what tallitot (or prayer shawls) are and why Jews wear them?

Well, in the Bible—in the Torah—God commanded that, if we wear clothes which have for corners (as was common in ancient times), then we were to add the tzitzit, fringes or knotted strings, on each of the corners. (Tzitziot is the plural.) This was one of the commandments of God. Today, because people don’t usually wear shawls or four-cornered garments, we make special garments—the talliot—with four corners.

We use them when praying, for example, mostly for the morning prayer. And also for Shabbat. We also have a tallit katan, or “small tallit”—which is like an undershirt with the tassels (or tzitziot) on the corners, and many Orthodox men will wear these every day. This helps us to remember, to strive to do (at all times) what God has commanded. It helps us to fulfill the mitzvot or commands because it reminds us of them.

You mentioned the tzitzit, or tassels on the corners. What more can you tell us about those?

In the Torah, God commanded: “Thou shalt make thee twisted cords upon the four corners of thy covering, wherewith thou coverest thyself.” [Deuteronomy 22:12] So, each tallit has eight strings (or four strings folded in half) on each corner. The strings are then tied into a series of five knots. Eight plus five equals thirteen. The word tzitzit, in its Mishnaic spelling, has a numeric value (in gematria) of 600. So, 13 plus 600 equals 613—and that’s the total number of commandments that appear in the Torah. So, when we wear a tallit with its tzitziot, we are reminded of all of the commandments we have an obligation to keep.

Now, Ashkenazi Jews and Sephardic Jews tie the tzitzit in different ways. They each make five knots, but the spacing between the knots is different, and Sephardic Jews intertwine a blue string (to act as the “tekhelet,” “shamash,” or the string that is wrapped around the other strings), whereas Ashkenazi tallitot typically have entirely white strings—even using a white string for the “shamash.” The tallit really should have the blue string. Blue is the color of the sky, and the sky reminds us of God. So, when we wear the tzitziot, we should remember that symbolism and, through it, remember God.

How long have you been hand weaving tallitot? And what got you into this line of work?

Oh, it’s been 16 or 17 years now. I started when I was 35. I was interested in art, and very much enjoyed it. I didn’t really know anything about weaving though. I was just looking for work and found this job as a weaver—making tallitot. So, I wasn’t trying to break into the business, or anything like that. I just needed something to pay the bills and that’s what I found at the time. I worked for that company for about five years, and then I started my own weaving business.

What does a typical day look like for you?

Well, its busy, and there are lots of things that happen every day. It isn’t just designing and creating. I talk to clients. I package and ship orders. I work with the seamstress. There is weaving and sewing. I have two weavers who work with me. Pretty much every day I make new designs and spend time working on a tallit. So, there’s much that has to be done on a given day.

From start to finish, how long does it take to make one tallit?

The whole process takes a few days just to create one tallit. It’s not cheap to produce these. I think most people would be surprised at all that goes into producing anything handmade—but particularly something like this.

So, do you design each of the tallitot yourself? Or do people come to you asking for a specific design that they've come up with?

I do most of the designing myself. Occasionally someone will approach me and want me to create one after their own design, but that’s not the case with most of the talliot I weave. There are some people who will ask me to add some colors to a tallit they own, or to spruce it up a bit. But, for the most part, I’m the designer.

Your tallitot are all unique. None, that I have seen, are the same. How do you come up with the designs you create?

Some might be surprised by this, but I don’t sit down and design them on paper before I make them. I usually don’t even have a plan before I start. I don’t try to envision the outcome prior to weaving. I literally just sit down at the loom and choose a color and start weaving, and the design just grows out of that that. I add a color here and take away a color there. It is quite random, which keeps them unique—each different from the next.

Other than earning an income, what motivates you to weave these?

Well, as we say (in the prayer we offer before we start weaving), “May this Tallit suffuse its wearer with happiness. May it bless the one wrapped in it with the blessing of heaven.” I believe that the tallit as the potential to help people be more spiritual. Morning prayers, Shabbat, the Holy Days, one’s Bar Mitzvah or Wedding—these are all times one would wear a tallit. These are very important and special days in one’s life. They are sacred times, and I get to play a part in these moments. That makes me very happy, and I hope the talliot I weave make those who use them happy, as they participate in these holy rites of passage.

As a follow-up to what you just shared, how has this work changed you for the better personally, or influence you spiritually?

To be able to work on something that makes people happy, something that brings some measure of joy to their lives—that has always felt significant to me. Rabbi Hezekiah [1659–1698 C.E.] said: “When the children of Israel are wrapped in their prayer-shawls, let them feel as though the glory of the divine Presence were upon them.” My work is to help them feel that divine presence, enveloping them as they read, pray, get married, or at other stages of their lives. That is sacred to me. It is very special.

Also, when I am weaving, I have time to listen to the Torah—to learn the word of God while I’m working. It is a very spiritual time. I pray, I meditate, I study Torah. The tallit is the product of that, but the activities that happen while I weave influence me personally and spiritually.

So, do you feel like you’re a more spiritual man than you would otherwise be, if you had chosen some other, perhaps secular, occupation?

Sure, I definitely think so. What I do is a spiritual thing, connected to Jewish history and Jewish practice and belief. It is very special to do this kind of work. And it would be hard to not be influenced by it spiritually, particularly if one were to take the approach I’ve tried to, of incorporating God, prayer, and scripture into how these tallitot are made. It has undeniably changed me and increased my personal spirituality.

What aspect of your work are you most proud of? Is it a particular tallit that you’ve designed and woven? The fact that you're doing something for God? What makes you most proud about what you do?

I think it would have to be what I mentioned earlier—that I’m able to make people happy through my work. Not all jobs can make that claim. What I create is used by people to connect with God and to feel His presence. That makes them happy and knowing that makes me happy.

I assume a tallit has to be “kosher” in order to be valid or authorized for use. What makes one kosher?

Yeah, well, the most important thing—the part that has to be kosher—is the tzitziot, the strings that we tie on the four corners. These have to be made in a certain way. They have to be handmade. So, the tallit itself doesn’t have to be kosher, so much as the fringes or tzitziot. They should be made from wool, and they should be handmade and handspun. As you pass the four strings through the hole in the tallit’s corner, you say “In the name of the mitzvah of tzitzit.” This prayer basically means that you are doing this in order to fulfill God’s command to you—His mitzvah to wear tzitziot, or fringes on your garment, and to remember the commandments they stand for. You must do this with meaning or intent.

Of course, though the fabric of the tallit doesn’t have to be kosher, you’re forbidden to mix wool and linen together when making one. Tallitot can be made from silk, cotton, wool, etc. But you don’t mix the fabrics. The Torah commands, “Do not wear clothes made of two kinds of material.” [Numbers 19:19] So, we don’t mix linen and wool when weaving a tallit. Some think that, since wool and linen are products with opposing characteristics, perhaps the command to not mix them represents the Law or Word of God versus the law or traditions of men. Mixing those together can be harmful to God’s people—so we don’t mix the fabrics as a reminder of that truth. I don’t know if that’s what is intended, but some believe that’s why we don’t mix linen and wool.

Do you have any experiences with making talliot that come to mind—unique or unusual things that have happened to you while interacting with customers?

Sure. One time I had a customer who had a dream about a special tallit. He saw the tallit in his dream, and he wanted us to make it based on what he saw. It was a tallit that had embroidered on it all of the names the cities in Israel—more than 100. In the dream, he was told to give this to the Prime Minister of Israel so that he could put it on and feel the responsibility of his job. So, we made that for him.

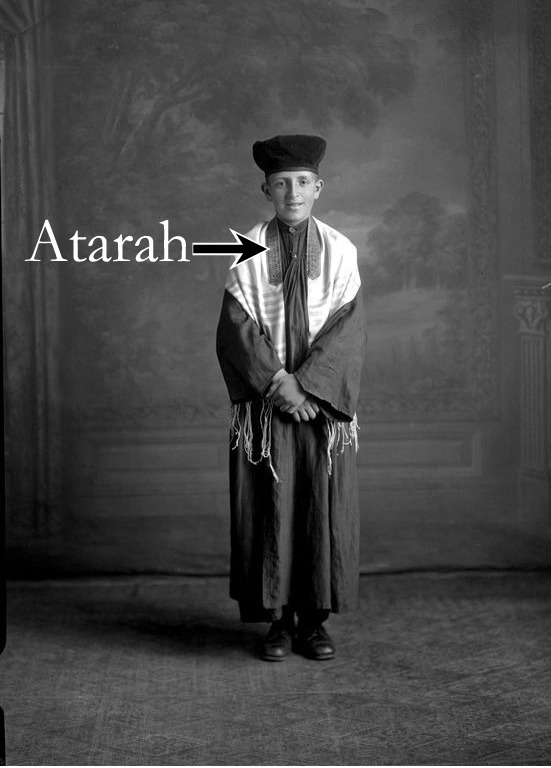

There was another experience—a touching one for me. There was a couple who lost a child in a car accident. The child was about nineteen as I recall. The mother sent me the atarah (the collar or “crown”) of her child’s tallit. It’s the part you put on your neck—that often has embroidery on it. She sent me that and had me make a tallit for her husband, using the atarah of her deceased child. It was a gift for her husband; a daily reminder of this child whom he loved and had lost.

Are there things about making tallitot that might surprise people? Common misconceptions or misunderstandings people have?

I think the most common is that a tallit has to be all black and white; that it can’t include any other colors. People are often unaware and surprised that they can be colorful and even quite artistic.

Your comment about the colors and embroidery reminded me of a comment by Maimonides [AD1138-1204], who said that it was “forbidden” to embroider verses of the Torah or a blessing on a tallit. Of course, we certainly embroider them today. So, the making of tallitot has changed over time. Do you see more changes coming in the future as it relates to the making or wearing of tallitot?

Well, in Hebrew Bible times, they were always plain—entirely so. No stripes. No bright colors. The tzitziot were attached to the corners of any normal, plain garment that had four corners. Then the white tallitot with black stripes and the tzitziot became the norm. And then ones with blue stripes. And then embroidery. Now they come in many colors and many designs—and with various things embroidered on them. I think, in the future, that will continue to grow, develop, and evolve.

Of course, you’re not likely to see a Haredi Jew wearing a colored tallit. This is something more common among the more “modern” Jews. So, not everyone is thrilled about the evolution or changes; and not everyone will partake of these newer styles of tallitot.

One thing that might be surprising is that, rather than more and more of these being made by machine, we’re actually seeing more and more handmade tallitot. More weavers are getting into the business of creating handmade and custom-made talliot. So, whereas some might expect this to go 100% automated, I think that it is actually moving more toward handmade talliot—which I think makes them more special and meaningful for the wearer (who has one unique to him or her).

Is there symbolism behind the tallit and wearing it?

Well, as I mentioned earlier, when people put it on, they should feel like they are being hugged or embraced by God—shrouded by Him. They should feel very protected. Also, there are the stripes. The Israeli flag’s design draws on the look of a traditional tallit—with white and blue. I’m not sure about the intended symbolism of the stripes on the actual tallit though. Some say it represents the heavens, with the blue sky and white clouds. When you wear it, you certainly should remember God. As I already mentioned, the tzitziot are to remind us of the 613 commandments given in the Torah and our duty to try to keep and live them.

Is there anything else you feel people should understand about tallitot and their use in Judaism?

I would just say that a handmade tallit is a bit like a piece of religious art. There is a difference between an actual painting and a print of that same printing—in the value, but also in the esthetic beauty. The original, the actual painting, is more special and more valuable in many ways. Having the original means you own something unique that no one else has. Your tallit is a sacred garment that you use to connect with God, and to keep the mitzvot He has given. Just as that relationship is special, that garment should be special. And whether you’re using a custom-made tallit, or a machine manufactured one, you should have reverence for the garment and the rites in which you use it, as they are a means of approaching the divine, which is a very sacred thing.

Interview conducted, transcribed, edited, and condensed by Alonzo L. Gaskill.

7/13/2022 10:02:42 PM