Religion Behind the Scenes spotlights the less discussed, but no less crucial, tasks that keep religious communities running, and the people who make it all happen.

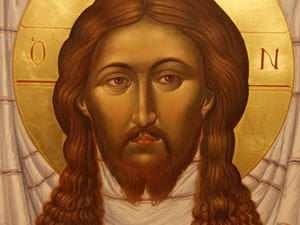

Anyone who has ever visited an Orthodox Church will sense the importance of icons (or religious art) in the worship of Eastern Orthodox Christians. Indeed, Orthodox bishop, Kallistos Ware, indicated that, for the Orthodox, icons are not simply something nice to have, but they are “essential” because icons are a doorway to the divine, helping the worshiper to draw closer to God.

Stan Kranidiotis is an artist, and an iconographer, who lives in Greece, and has been painting icons since he was a teenager. In this “Religion Behind the Scenes” interview, Stan takes us into the fascinating world of the icon artist.

How long have you been doing iconography?

So, I started to do the icons when I was 15. My father and my stepbrother became monks. My stepbrother was good at drawing, so he started to paint icons. And I just tagged along. I tried doing them. I didn't have the patience at that time. I just didn’t really want to do icons. I wanted to do modern art. Plus, I was a bit rebellious. You know, like all teenagers, right? I started painting professionally at forty. That’s when I started really getting into the Byzantine style paintings.

What was the thing that really drew you to paint icons, and to be involved in the more religious side of art?

So, what attracted me to icons in the later stage of my life was that I like to dabble in art. That was always painting. And I was initially just a job. Though, I have to admit that, when I was younger, I liked icons. I had my own little icons, which felt to me a bit like magic or good luck charms. I believed that they had a sort of supernatural power about them—whereas, having spent so many years producing them, I don’t now believe that they’ve got any supernatural qualities. Icons, to me, are a sort of an agent for the Greek people—an intermediary.

What does the typical day look like for you with your job as an iconographer?

The typical iconographer’s day is that you get up at eight o’clock, and you sit down and paint for an hour (with a timer), and you have a break. Then you start painting again for another hour and have another break. That goes on for about six hours (including all of the breaks) each day.

With regards to the creation of icons, what’s the most sacred side of the work?

Well, in the beginning of the process, there’s nothing sacred about it, because the image (at that stage) is unformed. It’s when it’s finished and goes to the church, to the special place where the priest performs the Metousiosis (μετουσίωσις)—where the bread and wine turn into the body and blood of Christ, right? (The Catholics call it “Transubstantiation.”) The completed icon stays in that special place for 30 days, and then it possesses the metaphysical properties, which Orthodox Christians believe that it does. So, that’s where the “sacred” side of the process comes in; where it develops or begins.

Since the clergy clearly have a role in the creation or sanctification of icons, do they also tell you what you should paint?

Yeah, they tell me what they want me to paint. Of course, the customer can also be a practitioner who has made a special promise to God or to a saint—a patron saint—that they will bring an icon to the church. It is called a “tama” (τάμα)—a votive offering. The commissioned piece of art, which they give it to the Church, is usually offered as an expression of gratitude for a special request (they made in their prayers) which God or the saint answered. (Some do it in the hope of an answer to a request they are making now, but which hasn’t yet been granted.) This is an ancient thing that the Greeks used to do, and examples have been found by archeologists. The ancient believers had special requests from the gods, and they would bring little ornaments made of gold, or silver, or clay, or whatever. They would place them in the appropriate place in their churches or at a shrine to the saint.

Do the icons have to be approved by clergy?

No, they don’t have to be “approved,” but they are kind of standardized, and you can’t really move away from that “standard” and just “do your own thing.” So, if we’re painting St. Paul, we follow our already established picture of him, such as a mural in a church somewhere, or an old icon of him, and we just copy that look. So, we can’t depart significantly from the established norm, or anything like that. But you’ll notice that, in the Byzantine style, the noses and the eyes are all typically the same—they follow the same pattern. So, they kind of all look alike.

What aspect of your work are you most proud of?

Well, the details of the paintings. I’m very good at details, for my age [66], because I can still see well; the details and the godliness coming through each of the images I create. If you get that right, then all of your icons will look good. But, if they don’t have that spiritual quality, you won’t be able to do icons that look like they’re not of this world; icons that look like they belong to the next world. I don’t know how to explain it. To compress holiness into a small space, such as that of an icon, is like shrinking the universe but still trying to recognize its components. That’s what I’m trying to do.

Do you have any unusual stories related to your work with regards to icons, or the creation of them?

Well, as I said, as an iconographer, there are no metaphysical qualities and nothing supernatural that happens with icons. But some people who use the icons I create believe that things happen that are miracles. I don’t know if, when miracles happen, they are related directly to the icon itself, or whether it was just the prayer they had uttered that provoked them. One time I had a crucifix to paint in a church, and the cross on which the image of Christ would appear was itself very high. I couldn’t get up there to paint it. So, I had to make the painting downstairs, and then cut it out of the canvas. I then had to stick the picture of Jesus crucified—which I had painted—onto the cross, which I couldn’t bring down because it was so high. So, I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to do it; that it wouldn’t work, that it wouldn’t look right. And I just kind of prayed about it. Then I was at the metro, and I looked down at my feet, and there was a picture of Christ on a cross. It wasn’t Easter or anything like that. I mean, you can’t find anything like that in the metro, especially in Greece, right? But there it was. And I picked it up, and I painted that on a canvas, and I cut it out. And then I found this guy, an electrician, and I said to him, “Can you get up there and stick this on that cross for me; and I’ll give you a painting or something as compensation—because it’s too high for me?” And I put some glue on it, and I sent it up to him, and he put it on. To my amazement, it was just right; it was the right painting for that size of a cross—though I had not been able to measure the cross before I made the painting. And, you know, everyone said, “Well, that’s a miracle!”—first of all, because I found something in the metro, which I never ever found again. And also, because the painting was the right size. And, you know, it just fit in?

One other time, I had to do a painting of three saints, which I didn’t have a picture for. When I got the order, I went down to the Monastiraki open-air market, here in Athens, and there on a table were two books. And on the front cover of those books were pictures of the saints I needed to paint. And the two books were being sold for one euro, and they were probably meant for me. I don't know. I never saw those books again, or before. Just on that particular day. What do you make of it? Right?

What are some aspects of the job of iconographer that might surprise people?

Sometimes the icons I’m painting turn out to be very, very good, which surprises me!

There are times when I’m painting something, and the image I am copying is so faded out or damaged that there’s almost nothing of the image that is recognizable. I've got to make it all up. And I don’t want to get away from the original because, as I noted, you’re not supposed to make things up too much—like you would when painting non-religious art. And because of the difficulty of seeing the original image, it makes you more creative; and it turns out to be a masterpiece.

What would you say is the most difficult aspect of making icons?

Sometimes, the sheer weight of the wood. My last icon weighed like 12 kilos, or almost 27 pounds. So, I had to find a creative way of painting it. I ended up doing it on canvas first, then I stuck it on the wood. That way, I didn’t have to manhandle a massive piece of wood because, with an icon, you’ve got to turn it around and around as you work on it from different directions. So, for example, it’s easier to do a vertical straight line than it is to do horizontal or oblique one. So, sometimes you turn your canvas sideways, so you can paint vertically. And you’ve got to have a very sturdy easel for a painting that is large or heavy—particularly when you’re paining on wood rather than canvas (which is the case for most icons). If you’ve got a 12-kilo weight that you’re moving around, it’s going to fall on your foot. So, that’s hard.

How has your experience painting icons changed you as a person or enhanced your spirituality?

Well, it helps to have something that you do, so that you feel satisfied that you’re doing something with your life that is not worldly. Painting icons, you feel like you’re going to be enlightened, and something will be revealed to you, just because you’re painting a religious scene.

Have you ever had times where you’ve been “enlightened” or you’ve had a spiritual experience as you were painting an icon?

Actually, at one point I had two frozen shoulders—and I couldn’t lift my shoulder; and I started to paint the shroud [of Turin], if you’re familiar with that, the shroud with the imprint of Jesus face. And I remember this painting because, by the end of the painting, I could actually lift my arms—and I think maybe painting that image helped. I wasn’t really experimenting to see if I would be healed, but it worked anyway. Like, I couldn’t lift my arm for about nine months but, after painting the face of Christ, it started to get better. It worked. Whether that was religious or not, I don’t know—but it made me happy.

What are some misconceptions people have about iconography?

Well, that that they will get rewarded by God because they commissioned someone to paint an icon. That, I think, is a misconception. Some assume that, without any righteousness on their part—without doing any good works—they will get rewarded, because they’re giving the Church something that looks nice, and then thinking God will be pleased with it. No one ever asked God if he is pleased, or if he condones the image that we give him in the form of an icon.

Another misconception is that an icon that’s hand painted, especially by a monk, somehow possesses special qualities. And, some think, possessing that hand painted piece of religious art brings something special to you. Of course, there is no proof of that, though some people believe it.

What motivates you to paint icons instead of non-religious art?

Well, in the beginning, I had grown up with the idea that some icons are miraculous; and that belief goes around quite a bit, particularly here in Greece. There are a lot of “miraculous” icons in Greece; they just springing up all the time. There are icons that cry, that have tears. There are icons that have miro, myrrh, or incense—they emanate this sweet fragrance, but we don’t know exactly how it happens. So, I tried painting icons, whether I would be blessed or not for making them. But, as the years go by, I’m just happy to bless other people—as long as they don’t treat the icons as an obstacle to their personal relationship with God. Unfortunately, some do. They say, “I’m in possession of something that’s gonna help me, and I don’t have to pray to God.” So, the icon can’t be the end of it; the end of one’s religious journey or experience. But it shouldn’t be.

How has the work of the iconographer changed over the last 40 years?

The style has improved because, in the beginning, people were trying to imitate the Byzantine style, and they weren’t sure how to do it. Until some people who are smarter than me found out how to structure the painting of the icons. And, of course, the materials have become better. For example, they used to use a lot of imitation gold, which is just brass. And now iconographers actually use pure 24 karat gold. I mean, the materials have improved; they’re better. Iconographers take a lot of care now.

Would you say that people today buy icons more for the art or artistic beauty, and less for the religious significance?

You’ve hit the nail on the head. Yeah, now there are icons produced not for religious purposes, but for decorative purposes—to go in someone’s living room or lounge, and they’re made to look old, because it looks like an archeological thing. They want to have an old icon that looks like it’s pretty expensive. So, some artists purposely make them look old by using old wood and glazing them with something dark, and just wiping over to give that antique look. That’s purely for decorative purposes and selfish purposes. Not for adoration or worship.

What’s the future of icons and iconography? Does it have a future?

Icons are here to stay; just as Greek culture is. That culture is being taught to young people, and icons are part of the culture, right? And, you know, if you take all these things away, you’re literally taking the ground beneath their feet. And everybody needs to know who they are. They need their culture, because it provides their identity, their beliefs. And everybody needs faith, and everybody has their own faith. For the Greek people—and Eastern Orthodox people, in general—icons will always be part of their faith, their culture, and their identity. That’s not going away.

Do you think changes in society will cause a decrease in the production of icons in the future?

Actually, the production of icons is increasing every year—especially in Agíou Órous. They are constantly out of stock and, more expensive—if a monk paints them, because it is seen as more holy or having some special power. Since communist rule has ended in many parts of the world, you have people who are religious tourists who come and buy lots of icons. Of course, there’s Orthodoxy outside of Greece, and they need icons as well. I mean, the Orthodox faith requires icons, it requires the agent—either the priest or the icon—to reach God. We’re not taught to have a personal relationship with God. We can’t because we’re sinners. So, the icon helps mediate that relationship for many Orthodox Christians. That’s my view as an iconographer.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Jared Gaskill. Jared is an undergraduate student at Brigham Young University, where he studies the Ancient Near East. He has a fascination with world religions, including Greek Orthodoxy, and—having lived in Greece—returns frequently, considering it his second home.

7/13/2022 10:02:12 PM