By Richard R. Gaillardetz - June 22, 2009

The question of authority in the Catholic Church -- a perennial source of interest and debate among Catholics themselves -- made international news recently with the story of the Vatican's move to reunite with the Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX), a group that, under its founder, Bishop Marcel Lefebvre, had rejected the reforms of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965). In light of the news that one of the prominent SSPX bishops denied the Holocaust, many Catholics were outraged at what they perceived to be an insufficient process of vetting the leaders of the group. Many perceived this incident as a failure of authoritative leadership. This raises important questions about the legitimate role of a formal teaching authority in the church.

The question of authority in the Catholic Church -- a perennial source of interest and debate among Catholics themselves -- made international news recently with the story of the Vatican's move to reunite with the Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX), a group that, under its founder, Bishop Marcel Lefebvre, had rejected the reforms of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965). In light of the news that one of the prominent SSPX bishops denied the Holocaust, many Catholics were outraged at what they perceived to be an insufficient process of vetting the leaders of the group. Many perceived this incident as a failure of authoritative leadership. This raises important questions about the legitimate role of a formal teaching authority in the church.

One of the distinguishing features of Roman Catholicism has been its consistent commitment to a formal authoritative church office charged with preserving the unity of the church and safeguarding the fidelity of its apostolic message. This formal church office has changed and developed, sometimes dramatically, over the course of two millennia.

In the New Testament we find a real diversity of leadership structures. However, by the end of the 2nd century a tripartite leadership structure emerged in which each local church was led by an individual bishop surrounded by a council of presbyters who functioned initially as pastoral advisers, and a group of deacons who engaged in much of the pastoral ministry of the local church. By the end of the 2nd century, the bishops were seen as the principal ministers charged with preserving the integrity of the core Christian message, the apostolic faith. These bishops exercised this authority both in their individual teaching within their local church and in their regular meeting in synods and councils with other bishops.

Over the course of the first millennium, even as episcopal synods and councils remained the primary way in which bishops exercised their teaching authority, one bishop, the Bishop of Rome, grew in influence and authority, particularly in the western church. Initially, this was a function of the unique prestige given to the local church of Rome, which had witnessed the martyrdom of not one but two apostles, Sts. Peter and Paul. In the 3rd century it began to be held that the bishop of Rome was the successor to the authority given by Christ to St. Peter.

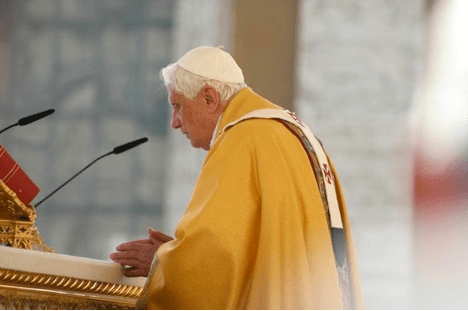

Gradually, over the course of the second millennium, the authority of the pope increased while that of bishops decreased. This gradual shift of authority from all of the bishops to the pope alone culminated in the 20th-century papacy of Pope Pius XII. The Second Vatican Council's doctrine of episcopal collegiality sought to redress this imbalance, teaching that the entire college of bishops shared with the pope, the bishop of Rome, authority over the whole church.

IS THE POPE ALWAYS RIGHT? WHAT CATHOLICS REALLY BELIEVE ABOUT PAPAL AUTHORITY...

In the midst of major shifts in the structure, scope, and exercise of this official church teaching office, it is difficult to identify a common thread. However, the late Dominican theologian, Jean-Marie Tillard, has suggested that the heart of this magisterial authority is tied to the notion of memory. Let us explore this further.

The core faith of the church has been handed on in a rich diversity of forms. While giving an obvious priority to the sacred texts of scripture, this core faith has also been handed on in the communal worship of the church (the liturgy), in the teaching of ancient church writers (the fathers and mothers of the church), and in the witness of the saints. This faith was handed on both in scholarly reflection and in the insight, testimony, and witness of ordinary baptized Christians. All of these expressions of the faith considered together constitute the Tradition of the church. Tillard suggests that this Tradition might also be understood as the church's corporate "memory." Even though, as the Venerable Bede put it, "each day the church gives birth to the church," as the church grows and develops it continues to draw on this dynamic memory in which we recall who we are called to be in Christ.

Seen from this perspective, Tillard contends that the bishops, including the pope, function as the ministers or servants of the memory of the church. This helps us remember that while the bishops are the authoritative teachers of the faith, what they explicate in their teaching is not something of their own invention; it is the faith of the church preserved in the memory of the entire people of God. This ministry of memory exists for the sole purpose of preserving the church's fidelity to a memory grounded in a message that is not of our own making, a message that comes to the church as a gift from God, through the power of the Holy Spirit, in the person of Christ. Consequently, although the bishops and pope are the authoritative teachers of the faith who give formal and normative expression to that memory, they must also be listeners and learners who themselves receive the church's memory through their participation in the life of the church.

Even as Catholics continue to affirm the necessity of this apostolic ministry of memory, new questions and challenges are emerging. We must distinguish between the necessity of a formal teaching office and the concrete way in which that office is exercised. Many today are scandalized by the exercise of a teaching office by those who seem unwilling to first listen and learn. Some are scandalized as well by draconian disciplinary measures imposed on theologians who struggle to find new ways to make sense of the faith of the church in changing historical and cultural contexts.

Finally, many believe that the authority of the pope and bishops is not enhanced but undermined when they fail to acknowledge that some pressing pastoral issues do not admit of simple solutions as well as when they fail to acknowledge the possibility of error in formal church doctrine (apart from the rare instances when they exercise the charism of infallibility). For Roman Catholicism the enduring presence of an authoritative teaching office plays a vital role in maintaining the church's fidelity to its ancient apostolic memory but it is also an office that, with the whole church, always stands in the need of reform and renewal.

Richard R. Gaillardetz, Ph.D., is the Thomas and Margaret Murray and James J. Bacik Professor of Catholic Studies at the University of Toledo in Toledo, Ohio, and the author of several books, including By What Authority?: A Primer on Scripture, the Magisterium, and the Sense of the Faithful (Liturgical Press).

1/1/2000 5:00:00 AM