By Peter Collins

By Peter Collins

I will fire four people next month, people who performed well and did what they were asked. One is an immigrant. Two have children. Three are in their late 30s and will wonder how to start over. All four will be stunned.

Everything I know about godly relationships suggests two things. First, I should tell them the bad news as soon as possible, in order to give them time to prepare. Second, I should tell them myself. Yet legal restrictions are not mindful of Christian love. Fear of litigation prevents the simple manager-to-employee apology: "I'm sorry, but we didn't make enough money and can't pay you."

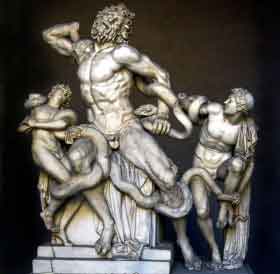

Instead my employees will receive the "Death Planner," which will tell them to go at a specified time to a conference room they have never seen on a floor they have never visited, where a senior executive whom they do not know will be attended by a human resources professional they never wanted to meet. The senior executive will read a script carefully composed by lawyers, stopping to insert the faithful employee's name -- "I'm sorry, um, Kevin, but..." -- and security guards will usher the broken people from the building.

These are my workers. They should be sitting across from me instead of the "firing squad." How am I supposed to think about this Christianly?

Every other part of the way in which I manage people is informed by my faith in Jesus Christ. This has (by God's great grace) given me a reputation as a strong developer of people within my company. We are in professional services, advising the world's leading executives at the world's greatest companies on their biggest challenges. Our business is built on having great people, and I have been blessed to oversee some of our very best. When my peers see the glowing reviews I receive from my team and ask what my management philosophy is, I do not have a fancy answer. All I say is, "I love my people."

My people know the names of my kids and the inside of my home. They invite me to their weddings, and they stay in touch after they have moved on. I love them and want the best for them - and I tell them so. I have given up my office and taken a cubicle so that the team can use "my" office for calls and meetings.

Loving people is the only way I know how to manage, and, fortunately, it turns out to be pretty effective. When a manager cares, he gets to know his people intimately. When he knows them, he understands their deep needs, joys, and motivations. Some employees need constant approval and public applause; others have a passion for learning and respond well to training opportunities. Managers who do not love their people miss these things. Their management becomes transactional. Their people lose passion, productivity falls, and the managers push them harder to no avail.

Sometimes, loving your people means encouraging them to find work elsewhere, in places better aligned with their passions and gifts. Whenever I have fired people for underperformance, I have sincerely believed that continuing to employ them was doing them a disservice. They were going through the motions, collecting paychecks, and destroying value. I nudged them out of a nest in which they had stayed for too long. To be sure, it was painful. I have never fired someone without crying in front of them. But the pain is like the pain of disciplining a child: you hate to do it, but you know it's right. When you fire underperformers, you release them to pursue their gifts elsewhere.

In this case, however, my employees are not underperforming, and they may never find a job better suited to their gifts. That's the first factor that makes these firings gut-wrenching.

The second factor is the abysmal job market into which they will be thrown. Let me be transparent: I really want to feel comfortable about firing these people. The last time I had to fire people, I slept uneasily until I knew that each of them had received the next job offer. I am looking for a way to have peace in a painful time. I also am not eager to resign my job in the midst of a recession over moral misgivings about the way that firings are handled at my company.

So these will be painful firings. Are they morally justified? Over and over I have asked myself this question. When I try to justify what I am about to do, this is the best I can come up with:

If I don't fire some people now, we as a company will lose money faster. If we lose too much money, ultimately I will have to fire more people than these four. So the best way to minimize total pain is to fire them now, get the business healthy again, and then add more employees later once the business is on sounder footing.