Mandala is the Sanskrit word for circle, and the great psychologist Carl Jung called it an “archetype of wholeness.” Archetypes are those basic patterns and symbols that repeat across cultures and traditions, emerging from a collective unconscious or shared well of images. Jung saw mandalas as expressions of the deep self’s longing for integration and a visual map toward our own spiritual centers. He would spend time each morning creating mandalas in response to his dreams and advised his patients to do the same.

The circle is a universal symbol appearing in nature -- think of the shape of the planets, moon, and sun. It is also found across religions -- think of the ancient stone circles found across Ireland or the intricate sand mandalas that Tibetan Buddhist monks create. We find it in the Catholic tradition as well. Consider the communion wafers we partake of each week or the wedding bands that symbolize the eternal nature of that sacramental commitment as elemental expressions of the mandala form.

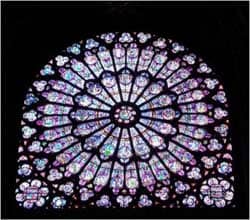

In churches we often find the more stunning displays of mandalas: the rose window. The first rose window was created about the year 1200 originating in France and then spreading throughout European churches. Considered part of French Gothic architecture, they are fairly characteristic of medieval churches.

The rose window functions on several different levels at once. Think about a time when you were inside a church and sunlight spilled through a stained glass window casting colored beams across the sacred space. This interaction between light, glass, and color sparks something transcendent within us. Our hearts feel lifted in their longings for the holy.

In rose windows, typically Christ or the Virgin Mary appears in the central rosette as the center point -- an expression of our desire for and movement toward holiness. In the petals surrounding the center may be images from the liturgical cycles and seasons of the year, the Saints and Apostles, the virtues, or sometimes the Zodiac. These petals act as paths guiding our eyes always back to the center. It is meant to be a symbol of our own spiritual journey and how to return back to that which is most important to us.

Domed ceilings in churches are another architectural expression of this sacred form, usually having a window up to the sky in the center, allowing the light to radiate into the building. Monasteries were often built around central cloisters. These were usually square in shape because of the building wall structure, but in the center there was often a lush garden or sometimes a fountain as an expression of God’s abundance and dwelling place at the center of monastic life.

Labyrinths are sacred circle forms being rediscovered today, with the most famous one at Chartres Cathedral in France. They contain a circuitous path that eventually leads to the center and are symbolic of the soul’s journey to the divine center within. In the middle ages, labyrinths were used as metaphorical pilgrimages for those who could not journey to the holy city of Jerusalem. Walking a labyrinth is a profoundly meditative experience, in part because the circular journey helps to integrate both sides of the brain in prayer and so frees the mind from a strictly linear way of approaching God.

Rosaries are also examples of the sacred circle as a form to support prayer. The word “rosary” comes from the Latin for “garland of roses.” In Catholicism the rose symbolizes the Virgin Mary and the layers of petals draw our awareness toward the center. Praying the rosary is a kinesthetic experience of holding each of the round beads between our fingers and repeating our prayers as our hands also move around the circle, offering us an experience of wholeness through both word and body.

Mandalas or sacred circles offer us a template for the interior journey to the heart of ourselves where we encounter the heart of God present as well.

Suggestions for Prayer:

Find an image of a rose window and spend some time in meditation with it. Take some time to connect with your breathing and then gaze upon the image as a tool for centering.

Pray the rosary holding the sacred circle in your awareness as you move through the beads.

Find a labyrinth near you (use the Worldwide Labyrinth Locator http://labyrinthlocator.com/) and take a meditative walk to its center and back out again. Notice how you feel as you enter and as you depart its sacred space.

Read Part 2 of our series on mandalas next week at Patheos.

Christine Valters Paintner, Ph.D. is a Benedictine Oblate and the founder and director of Abbey of the Arts, a non-profit ministry integrating contemplative practice with the expressive arts. She teaches at Seattle University’s School of Theology and Ministry and also works as a spiritual director, retreat facilitator, writer, and artist. She is the co-author of Lectio Divina: Contemplative Awakening and Awareness from Paulist Press. Visit her website www.AbbeyoftheArts.com.

Photo: Kayce Hughlett

7/28/2009 4:00:00 AM