By Patheos staff

The festival called "Day of the Dead" actually consists of two separate days: All Saints' Day on November 1st, and All Souls' Day on November 2nd. Both of these make up an important part of liturgy in Western Christendom.

The festival called "Day of the Dead" actually consists of two separate days: All Saints' Day on November 1st, and All Souls' Day on November 2nd. Both of these make up an important part of liturgy in Western Christendom.

All Saints' Day is a day on which to commemorate all the saints of God. As an inclusive holiday, it encompasses saints who are both canonized and not canonized, and even those unknown.

On All Souls' Day, the church remembers those who died in good standing, or the "faithfully departed." The day is set aside to celebrate and honor the deceased in heaven, to pray for those still in purgatory, and to thank and supplicate the dead for interceding on behalf of the living.

Although their origins are not known, these days were celebrated widely by the ninth century C.E. Their importance has risen steadily ever since, and especially in the 14th century, when the celebrations became widespread. Despite this, All Souls' Day never obtained official liturgical status; it has acquired its status only by custom. This seems to have been the result of the Church's fear that the festival would be viewed as polytheistic or as reminiscent of ancient Roman cult of the dead.

All Saints' Day, on the other hand, achieved official liturgical status by the Middle Ages. Interestingly, it actually had been strongly influenced by polytheistic traditions. Germans and Celts both celebrated rites at the end of the harvest season, in which they honored agricultural gods. This survived in the British Isles and is known today as Halloween. By the 15th century, Halloween had become a mixture of English, Scottish, Welsh, and Irish Catholicism. Ever since, Halloween has been closely linked with both All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day.

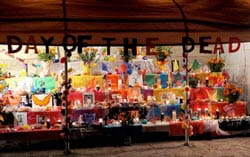

These festivals are especially important in Mexico, where it is called "Todos Santos" (All Saints' Day) and "Dia de los muertos" (All Souls' Day). The two days are often viewed as forming one holiday. After Christmas and Easter, this is considered the third largest religious celebration. Three main parts of the festivities include: offering dedications to the deceased, decorating graves at the cemetery, and celebrating the dead between Palm Sunday and Easter Sunday. These components all have references to pre-Hispanic times. Mexicans mix these elements with the Christian tradition, which was introduced to them by friars in the 16th century. For example, on November 1st and 2nd, those who have migrated to the city return and visit their community of origin. Together with their relatives, they commemorate the dead.

Yet the Day of the Dead lasts beyond these two days: celebrations take place from a week before November 1st to a week after. During this time, one exchanges gifts, renews friendships, and visits with family members. Like Halloween, it is a harvest festival and occurs in the autumn. But unlike Halloween, the Day of the Dead is not about spookiness or scary stories of random ghosts and goblins. Rather, it is reflective and centers on anecdotes and memories of specific deceased relatives.

Despite this, images of dancing skeletons adorn homes and stores in Mexico during the Day of the Dead. One of these has even been named "Katarina"; dressed up in an elegant hat and dress, she is a ubiquitous sight during the holiday. She often lurks near the family's homemade altar, which is decked with flowers (usually marigolds), fruits, vegetables, incense, and photographs of the dead. In addition, the best foods are left out for the deceased, including moles and tamales, special "bread of the dead" (pan de muerto), pumpkin candy, and liquors.

Cemeteries become similarly bright and decorative places during this holiday. Like the home altars, tombstones are cheerfully lit with candles and adorned with pictures, flowers, and food. Families sometimes hold all-night vigils there, during which they sing favorite songs of the deceased and tell stories.

10/22/2009 4:00:00 AM