By Thomas Kidd

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 spawned a spate of conservative Christian reflections on the essential characteristics of Islam. Figures from Christian Broadcasting Network's Pat Robertson to Colorado Springs pastor Ted Haggard pointed to the inherently violent nature of Islam. Liberty University's Jerry Falwell said on "60 Minutes" that "Muhammad was a terrorist," a glib comment that set off riots among Asian Muslims, and earned him a fatwa from an Iranian cleric calling for Falwell's assassination.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 spawned a spate of conservative Christian reflections on the essential characteristics of Islam. Figures from Christian Broadcasting Network's Pat Robertson to Colorado Springs pastor Ted Haggard pointed to the inherently violent nature of Islam. Liberty University's Jerry Falwell said on "60 Minutes" that "Muhammad was a terrorist," a glib comment that set off riots among Asian Muslims, and earned him a fatwa from an Iranian cleric calling for Falwell's assassination.

As recently as 2006, even Pope Benedict XVI generated a major controversy by making disparaging comments about Islam's violent history. One might think that these Christians' views simply represent angry reactions to the horrific violence of 9/11 and ongoing jihadist terror. But a closer look reveals that American Christians have deep-rooted views of Islam as a violent, demonic religion.

Pastor Aaron Burr, Sr. (the president of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, and the father of the politician Aaron Burr who killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel), expressed widespread Anglo-American Protestant sentiment in a 1756 sermon in which he discussed "the false prophet and grand impostor Mahomet." According to Burr, the early medieval period represented a dark night for the Christian church for two primary reasons: the rise of the Catholic papacy, and the spread of Islam. Muhammad brought Arabia under his control by violence, as he taught his followers that Islam should be "propagated by the sword, and that it is meritorious to die for it." Misery, woe, and ignorance followed in Muhammad's wake, and compounded the sufferings of God's true church in the world.

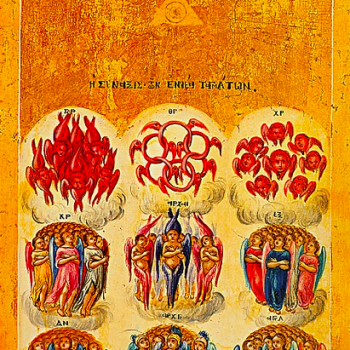

Burr, like most prominent Anglo-American theologians of that time, believed that the advent of Islam had been predicted in the Bible, particularly in the book of Revelation. Most conservative American Christians now think that the prophecies of Revelation point to future events, but early Americans saw many of the prophecies as already fulfilled in history. Burr shared the common opinion that Revelation 9:2-3, which speaks of locusts coming out of a smoky abyss, was fulfilled with the coming of Muhammad. Like most colonial observers, Burr saw Muhammad as the worst kind of religious "impostor," who pretended to have received revelations from God in order to gain power.

Since the colonial era, conservative American Christians have maintained a conflicted attitude toward Muslims. They have portrayed Islam as having malevolent origins, but they have also kept faith that Muslims would eventually convert to Christianity. Despite the overwhelming difficulties of Muslim evangelization, anecdotal accounts of Muslims becoming Christians were steady-sellers in colonial and antebellum America. Probably the most famous Muslim conversion narrative in the 19th century was the account of Abdallah and Sabat, told in a sermon by British pastor Claudius Buchanan. This compelling, tragic tale of the Arabian friends' journey to faith in Christ was printed in various forms throughout Britain and America from the early 19th to the early 20th century.

Conservative Christians have hardly lost their taste for Muslim conversion stories, as demonstrated by books like Bilquis Sheikh's I Dared to Call Him Father (1978). In this autobiography, Sheikh, a Pakistani noblewoman, recounted her conversion to Christianity following a series of dreams and visions about Jesus. The book defined the ideal Muslim conversion for a generation of Christians. It has been translated into many different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Finnish, and Amharic (a Semitic language spoken in Ethiopia), and it remains in print today.

Despite their hopes for Muslim conversions, American Christians have also anticipated that Islam would meet its demise in the end times, when Jesus would return to earth and establish his kingdom. In early America, many Protestants believed that Islam and Roman Catholicism would be destroyed simultaneously. Some even saw the two as the eastern and western Antichrists. The expectation of Roman Catholicism and Islam's downfall, and the imminent return of Christ, led to bold date-setting in the early 19th century, capped by the forecasts of William Miller and his followers, who expected the end to come in 1843.

Jesus' failure to appear at the appointed hour helped to transform standard Anglo-American interpretations of Bible prophecy, and by the early 20th century "dispensational" theology had become dominant in conservative circles. Dispensationalists began to anticipate the re-establishment of the state of Israel, where the final battle between good and evil would transpire. The founding of Israel in 1948 and the subsequent struggle between Israel, the Palestinians, and the Arab states has become the frame for many conservative Christians' interpretation of prophetic scenarios.