By the Rev. Tim Mooney

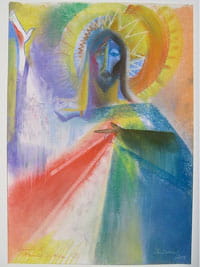

photo courtesy of Stephen B. Whatley via C.C. License at Flickr

Scripture Readings:

Scripture Readings:

Psalm 51:10-17; Philippians 2:1-11; Matthew 9:9-13

"Go and learn what this means," Jesus says. "‘I desire mercy, and not sacrifice.'"

Mercy is the English translation of the Hebrew word chesed, which means loving-kindness. It speaks of God's tender compassion toward humanity in our weakness, misery, and helplessness; it speaks of God's continued forbearance toward us when we are slow to follow, to keep God's covenant, to remain faithful; it names God's loving, generous, kindly disposition. Loving-kindness, mercy, is what God desires.

The notion of sacrifice in the Bible is based on three underlying ideas: 1) It is a gift of gratitude to God. This idea most closely resembles mercy, because it is unconditional, a gift given out of love, without any strings attached. 2) It is a means of winning God's favor and entering into a favorable relationship with God. It's a way of getting God's attention, of earning God's favor in order to cover one's sin or gain good fortune in battle. 3) It is a means of releasing and gaining more life. This understanding of sacrifice comes directly from the slaughter of animals that was so much a part of religious ritual in ancient times. The idea behind animal sacrifice was that by shedding blood, an animal's potent life force, believed to be held in the blood, was released for God's benefit or for the one making the sacrifice.

The book of Leviticus in the Old Testament is a highly detailed depiction of all the appropriate sacrifices God required of the Hebrews. It seems to reflect a heavy dose of that human tendency to try and earn God's attention and favor by setting up a system of sacrifices. While reading through parts of Leviticus the other day, the whole sacrificial system struck me as a well-organized business. God's forgiveness and favor is in high demand, and this system, run by the priests, is the only way to procure it. It's no wonder that it occasionally got out of hand. When Jesus overthrew the tables of the money-changers in the temple he was attacking the flaw that exists at the center of the sacrificial system. When Martin Luther posted his 95 theses on the Wittenberg Door in the 16th century, he was attacking that same flaw, only this time found in the system of religious indulgences that had run amok in the Catholic Church.

Thank God we're past all that now! Thank God we're past all that primitive, sacrificial stuff. We're much more enlightened now. We don't really need Jesus to remind us anymore to know the difference between mercy and sacrifice because we're beyond that whole sacrifice thing!

For one, we don't do blood sacrifices. I'm particularly grateful for that. Being a pastor would be awful messy. You know, slaughtering animals on the altar, splashing blood with ritual solemnity. I'd have a horribly high dry-cleaning bill, although my freezer would always be chock-full of meat. Being a parishioner would be messy, too. You'd have to find a way to get your best bull or ram into the back of your SUV in here. Or maybe it's not too different than trying to drag your spouse to church when the Broncos are playing the early game.

And another thing. Since the Reformation, we Protestants anyway got rid of the whole priestly thing. We don't need an order of priests to mediate between ourselves and God. We claim a direct line. We believe in the priesthood of all believers. No more blood sacrifices. No more priests. So Jesus' words, "I desire mercy, and not sacrifice," really don't apply to us. Right?

I'm sorry to say this, but we are still in the business of making sacrifices. We don't shed the blood of animals. But how often have we said to ourselves under our breath, "I've put my sweat and blood into that and look what I get in return." Or "I've poured out my soul and does anyone care?" You see, we've made certain sacrifices. And we've kept a secret ledger. And that means that we're better. And there is an expectation that we've earned something from God in return. We rarely ever do this consciously, but we do it. In this way we are like the Pharisees to whom Jesus addressed his words. They had chosen a religious path that they saw as sufficient, as more than enough, particularly in comparison to others. Granted, their lives were difficult, living according to a bunch of purity rules and rituals. After all, they had built their lives around these rituals. They had gone out of their way. They had made sacrifices.