By Jonathan Partridge

Televised scenes of crumbling buildings, thunderous explosions, and white phosphorous smoke played throughout the world earlier this year during Israel's 22-day invasion of the Gaza Strip. The incursion in January and late December came after Palestinian militants had fired a slew of rockets into southern Israel, following an Israeli blockade of the region. When it was all over, outgoing Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert said his country had exceeded its goals, while more than 1,300 Palestinians and 13 Israelis were dead according to some counts.

Televised scenes of crumbling buildings, thunderous explosions, and white phosphorous smoke played throughout the world earlier this year during Israel's 22-day invasion of the Gaza Strip. The incursion in January and late December came after Palestinian militants had fired a slew of rockets into southern Israel, following an Israeli blockade of the region. When it was all over, outgoing Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert said his country had exceeded its goals, while more than 1,300 Palestinians and 13 Israelis were dead according to some counts.

More than 7,500 miles away, Ali Malik participated in a Jan. 8 campus protest against the invasion with other members of University of California, Irvine's Muslim Student Union, while senior Isaac Yerushalmi helped run a counter-protest of pro-Israeli Jewish students against Hamas.

Tensions at the university over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have become well known. MSU's annual Palestinian Awareness Week each spring has garnered protests from local students and other Jewish groups in part because of a display of the "apartheid wall" -- or "security fence" as Israeli government officials prefer to call it -- that divides Israel from the West Bank and cuts through parts of the occupied territory.

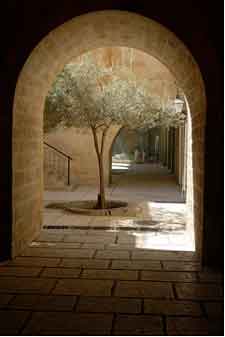

But a change in Jewish-Muslim student relations may be taking place. Less than a week after the Gaza protest, Malik and Yerushalmi joined other speakers to discuss a trip that they and thirteen other students had taken to Israel and the West Bank the previous summer through the university's Olive Tree Initiative program founded in March 2007. Students involved with the program continued to communicate with one another throughout the invasion, even while holding vastly different opinions about the military campaign.

"The big issue is to continue this initiative," said Malik, as he discussed the ongoing dialogue process among group members. "You can't let one flashpoint ruin the whole peace process."

While Israeli and Palestinian officials continue to struggle in their quest to bring about Middle East peace, dozens of programs like the Olive Tree Initiative are conducting their own reconciliation work. Cynics often question the merits of such endeavors, picturing small groups of people holding hands and exchanging niceties while people are slaughtered in conflict. In fact, some dialogue groups fail to weather the tension during cataclysmic events such as the Gaza invasion.

Other groups not only pull through the strain; their discussions about the tragedy help strengthen bonds and create deeper understanding. It all comes down to a matter of faith: a belief that discussion and meaningful relationships can enhance world peace, even if only in small ways.

"The point is to grapple with disagreements and still recognize the other's humanity," said Brie Loskota, managing director of the University of Southern California's Center for Religion and Civic Culture, who has studied interfaith dialogue extensively and has helped start several initiatives.

It's a fine line that many groups engaged in reconciliation work must tread carefully.

Beyond ‘Kum Ba Yah'

Beyond ‘Kum Ba Yah'

The mere mention of the words "interfaith dialogue" elicits derision from many people who deem the practice to be a meaningless gesture.

It's a constant frustration for Loskota. She has seen positive impacts of dialogue through her past work with Seeking Common Ground, a Colorado-based organization that brings together people from regions of conflict, including Israel and the Palestinian territories. Yet Loskota is aware that the dialogue label often has negative connotations.

"People think it's about inaction. They think it's about just talk."

Jacob Rich, a second-year law student at USC, is among those who are cynical of at least some types of dialogue. Rich, who regularly attends Shabbat services at USC's Chabad House, inadvertently walked into a Muslim-Jewish event there last November, and was not particularly impressed. A speaker at the event stressed that Jewish people need to help combat Islamophobia in the United States, but Rich felt that was an impossible task for Jewish Americans to accomplish on their own and should be addressed by Muslims themselves.

While Rich said dialogue is important, he believes rhetoric alone is insufficient.

"I don't care about words," Rich said. "I care about action."