By Vince Nobile

In a matter of weeks, Americans will engage in the Christmas ritual of visiting Bedford Falls, U.S.A., home to George and Mary Bailey, Uncle Billy, Bert and Ernie, Violet Bicks, and mean Henry Potter. It's the time of year for everyone's favorite holiday rerun, Frank Capra's 1946 classic, It's a Wonderful Life. Americans have been watching this film for more than half a century, but have long ago abandoned its message. In his time, Frank Capra was a persistent advocate for core cultural values. Today, conservatives and new Democrats alike bemoan the absence of core values, though I doubt they want to adopt those of Bedford Falls.

In a matter of weeks, Americans will engage in the Christmas ritual of visiting Bedford Falls, U.S.A., home to George and Mary Bailey, Uncle Billy, Bert and Ernie, Violet Bicks, and mean Henry Potter. It's the time of year for everyone's favorite holiday rerun, Frank Capra's 1946 classic, It's a Wonderful Life. Americans have been watching this film for more than half a century, but have long ago abandoned its message. In his time, Frank Capra was a persistent advocate for core cultural values. Today, conservatives and new Democrats alike bemoan the absence of core values, though I doubt they want to adopt those of Bedford Falls.

If the political and cultural pacesetters of our time are any indication, the wonderful life of Capra's film bears little resemblance to our aspirations. The current fascination with the rich, the powerful, and the famous is not found in Bedford Falls. To Capra, the rich and powerful had none of the essential qualities to preserve freedom in America, nor did they display any of the core cultural values he championed. Henry Potter, the film's consummate big money capitalist, is half a man physically, existing entirely from the waist up. More importantly, what remains of his humanity is the part triggered by cold monetary self-interest. Potter has neither family nor friends. His only social relationships are those attached by what a wise philosopher once called the "cash nexus." Unlike his nemesis, George Bailey, Potter is intolerant of America's working class and its ethnic minorities. Potter refers to the former as "suckers" and "riff raff," and the latter as "garlic eaters." In short, Capra depicts big time capitalists as bigoted predators, itching to direct America toward a predatory existence under their domain.

It's A Wonderful Life warns that a predatory capitalism could prevail unless regular Americans reconcile the tension between self-interest and the communal spirit -- each with a grip on our national consciousness. George Bailey not only embodies this conflict, he provides the object lesson for its resolution. He fights the temptations of self-interest every time he tries but fails to "shake the dust off [that] crummy little town." In the famous parlor scene where George and Mary share a phone call from "Hee Haw," Sam Wainwright, George insists he "doesn't want any ground floors," he "doesn't want to marry anybody!" Just before succumbing to his repressed love for Mary, he says, "I want to do what I want to do!" Of course, George never does what he wants, for, as a more contemporary George (Costanza) has said, "A George divided against himself cannot stand." Time and again, George B. sets aside "independent George," and for good reason. To do otherwise would condemn Bedford Falls to Potter. Even George and Mary's planned honeymoon, financed by their hard-earned rainy day money, is too risky to the fabric of the community.

George Bailey is Capra's consummate peoples' hero using his money and his business only as a way of helping family, friends, and community. Herein lie the essence of Capra's Americanism and his model for generating a wonderful life -- a people's capitalism. Such a capitalism exists when one's commitment to giving takes priority over self; when the well being of the self is rooted in the well being of the community, and when the profit motive is employed to meet societal needs, rather than stock dividends. Like many Depression-era Americans, Capra had little faith left in the promises of laissez-faire (i.e., the pursuit of self-interest as parent to the common good). What is good for Potter is emphatically not good for Bedford Falls.

The humane capitalism of Capra's film was not inevitable. A possible alternative is glimpsed, should the "true American" succumb to the temptations of unbridled individualism. It is "Pottersville," a place marred by divorce, broken families, pornography, shootings, and police chases; an existence that "makes men want to get drunk fast," according to Nick the bartender. Pottersville turns the innocent flirtations of Violet Bicks, easily accommodated in the nurturing environment of Bedford Falls, into prostitution and self-destruction. It is an all-against-all, spiritually unrewarding society where the entrails of misery and alienation are easy to find -- kind of like L.A.

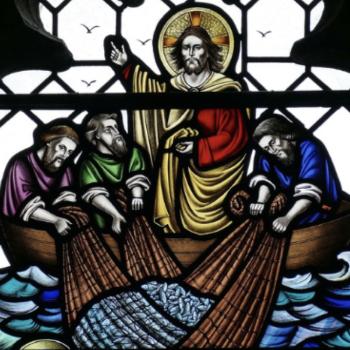

Judging from the film's ending, Capra did not think Pottersville was likely. There were far too many George and Mary Baileys dedicated to the well being of others. Moreover, Capra saw the values of a people's capitalism enduring since they were consistent with the ethics of the heavens. After all, George's guardian angel, Clarence, had to help others before he could earn his wings. No, once committed to the core values of a people's capitalism, the U.S. could beat back all threats, foreign and domestic.