Assumptions about History and Prophecy

Assumptions about History and Prophecy

The first and most obvious concern that historians raised about the unity of the text of the Torah deals with the fifth book, Deuteronomy. The focus of the book on the unity of the people of Israel and its unified worship in a single place, and the illegitimacy of any worship outside of Jerusalem are concerns that do not seem to fit with most of Israelite history until the late seventh century B.C.E. Strikingly, at that point, during the reign of King Josiah, a book is "discovered" during repairs to the Temple, which become the basis for "reforms" that align almost perfectly with the language and concerns of the book of Deuteronomy.

For historians, this establishes the promulgation of the book of Deuteronomy as having occurred during the reign of Josiah. More literal believers accept the biblical account, and may acknowledge that it was, indeed, the book of Deuteronomy that had been lost. Its loss explains the lack of adherence to its norms in the intervening years as well as the zeal with which Josiah instituted its reforms.

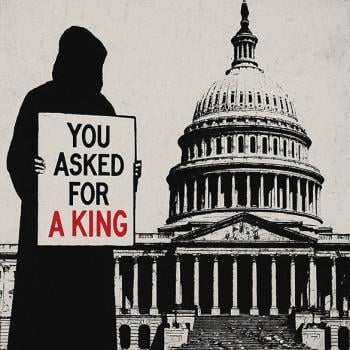

Another example is the story of the golden calf in Exodus 32. After Solomon's reign, the northern kingdom of Israel separated from the southern kingdom of Judah. The northern king Jeroboam established cult centers at Bethel and Dan, setting up golden calves as objects of worship and announcing, "Here are your gods, Israel, who brought you up from Egypt" (1 Kings 12:28). If a story of Israelite rebellion in the worship of a golden calf had been part of the Torah prior to Jeroboam, it is difficult to believe that Jeroboam would choose the same symbol, and it is inconceivable that the book of Kings would not condemn him explicitly for following that bad example. Consequently, historians see the Torah's golden calf story as a polemic against Jeroboam, cast back into Israel's mythic past. A traditional explanation would assert that Jeroboam's adoption of the golden calf merely shows how rebellious and twisted he was; the book of Kings would not have to refer back to the Exodus incident because it would have been obvious and self-evident.

Theological Understandings of the Torah

Theological Understandings of the Torah

Classically, Torah is understood as the content of God's revelation at Mount Sinai. For some, that means that the exact words of the Torah, each word and each letter, come from God. Unlike any other prophecy, the revelation to Moses was perfect and clear; for many traditionalist Jews, these assumptions are necessary in order to remove any question of human imperfection or mediation from the foundation of all Jewish belief. If the Torah isn't true, some assert, then all of Judaism is based on something false. Tradition, according to this stance, provides an adequate lens through which to understand Torah. Some who maintain this position question scientific beliefs that don't accord with a simple reading of the Torah -- they may say, for instance, that dinosaur bones were planted by God in order to test our faith -- and some harmonize or explain away scientific findings that disagree with Torah, arguing, for example, that the length of the days of creation could have been millions of years long, thereby synthesizing evolution and the creation story of Genesis.

For many modern theologians, beginning with Martin Buber, the content of revelation is not the Torah itself. Revelation is the encounter with God; Torah is the human testimony that Israel experienced this encounter. For some moderns, the idea that God actually spoke is theologically problematic: If God does not actually have an outstretched hand, why should God have vocal cords? More to the point, however, is the belief that the human component in determining God's will (which is later expressed through interpreting the Torah) is often seen as an ongoing process that had its origins in the Sinai experience itself. In this view, God is revealed in revelation, and Israel responded in each generation with torah (teaching) that was finally canonized as Torah and then supplemented with Oral Torah.

An intriguing approach expounded by the contemporary scholar David Halivni is that God indeed revealed a complete Torah to the people, but Israel sinned. Immediately upon receiving the Torah, the Israelites fell into the idolatry of the golden calf, and not until the return from the Babylonian exile under Ezra did Israel re-affirm its commitment to God. From Moses to Ezra, the Torah was preserved in a fragmentary state, but under Ezra, revelation was restored. The Torah that Ezra restored, however, has all of the signs of imperfection and human composition that the critics have identified, but the Torah is nonetheless the best restoration possible. Halivni's solution acknowledges the arguments of the critics, while affirming a faith in God's revelation of real objective content to the people of Israel.