By Beth Davies-Stofka

Starring: Denzel Washington, Gary Oldman, Mila Kunis, Jennifer Beals

Starring: Denzel Washington, Gary Oldman, Mila Kunis, Jennifer BealsDirected By: Allen Hughes and Albert Hughes

Produced By: Joel Silver, Denzel Washington, Broderick Johnson, Andrew A. Kosove and David Valdes

Distributor: Warner Brothers Pictures

Rating: R for some brutal violence and language

Run time: 1 hr. 58 minutes

In their new film The Book of Eli (opening in wide release on January 15), the Hughes brothers set up a tent of predictability, and then do really cool things inside that tent. After all, if you've seen such sci-fi dystopias as Mad Max, Le Dernier Combat, and The Omega Man, or Westerns from the hands of masters like John Hughes, Sergio Leone, or Akira Kurosawa, then you can probably imagine the general contours of The Book of Eli. But what makes the movie worth the visit to the theater is its highly unusual choice of topic: religious scripture.

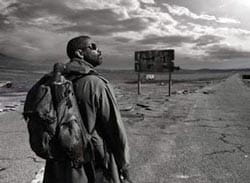

Eli is a walker. In fact, he's been walking for thirty years through a scarred and barren post-apocalyptic landscape. Thirty years ago, war severely damaged the planet's protective atmosphere. Now the sun is too bright and too hot. Plant life is dead. The only survivors are carnivores and scavengers: roaches, mice, cats, raptors, and, of course, humans. Very few humans survived the war. The under-30s, with no memory of the days of nature and civilization, use any tool at hand to prey on each other. There is a baffling availability of gasoline, but water is really scarce.

Eli survived the war, and is on a quest to deliver the precious book carried in his pack to a place he only calls "West." Given the ruined and dead landscape of his world, we don't know where he actually is, how far he's come, or how far he has to go. But he is determined to stay on his path and reach his destination, and he doesn't let anything stand in his way. He's an absolutely brilliant marksman and can easily defeat gangs of opponents in hand-to-hand combat. The first fight scene, exquisitely filmed in silhouette, is a work of art worthy of a graphic novel. It is also the most significant moment of foreshadowing in the movie.

Eventually Eli's travels take him through a town run by another man over thirty, an intelligent, literate, ambitious, and self-interested town boss named Carnegie (and the reference must be intentional). Carnegie pays thieving and murderous gangs for books, as many as they can find. When we first meet him, he is reading a biography of Mussolini. But there's only one book Carnegie actually wants, and he quickly discovers that the book he wants is the one Eli carries. At this point, it's likely not a spoiler to let you know that Eli's book is the Bible.

What commences is a classic Wild West struggle between these two men for possession of the Holy Word of God. Eli is tracked, pursued, and shot at, and defends himself brilliantly even after becoming the reluctant protector of Carnegie's teenaged stepdaughter, who insists on tagging along. The movie's third act culminates in a satisfyingly complex shoot-out with enormous casualties on both sides.

Why such violence over a book? Well, it turns out that Eli might have the only copy. And Carnegie understands its power to manipulate people. Carnegie knows he can use it to bend people to his will. He can use it to build an empire.

But Eli knows something about it, too. He knows it can raise people to a higher purpose, opening them to the possibility that it is better to give than to receive. He understands its power to inspire comfort and hope, inspiration and faith.

And so The Book of Eli presents scripture as a double-edged sword. Which of its qualities will prevail: its fascistic potential, or its potential to liberate us into selflessness? The movie's fourth act bursts into unpredictable terrain that will leave you surprised, puzzled, and amazed.

See this movie. Its unusual and uncluttered look draws you in, and there is just enough comic relief to keep you there. With almost no lines to speak in the movie's first act, Denzel Washington makes you love Eli, and with just a few short lines, Gary Oldman makes you deeply wary of Carnegie. You'll rarely see such an interesting story told about the power of scripture. But if you plan to see it, go soon, before someone spoils it for you.

Beth Davies-Stofka teaches courses on comparative religion and the philosophy of religion. She has also been an online columnist and critic and contributes regularly to the Patheos site.

1/18/2010 5:00:00 AM