By Christine Valters Paintner

All images © 2010 Christine Valters Paintner. All rights reserved.

Here I am.

This is the body-like-no-other that my life has shaped.

I live here.

This is my soul's address.

-- Barbara Brown Taylor, An Altar in the World: A Geography of Faith

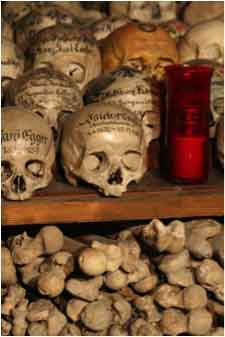

Two summers ago I was traveling in Austria and visited the tiny village of Hallstatt. Perched between a mountain and a lake, Hallstatt is best known for its early Celtic heritage and the treasures of ancient remains discovered there. But next to the Catholic Church is a tiny chapel, a bone chapel. You see, the cemetery is so small that bones had to be removed periodically to make room for the newly dead. The skulls were bleached in the sun and then lovingly hand-painted by family members with names, dates, and decorations. Standing in the room with 600 adorned skulls was a transcendent experience. I was brushing against my own mortality, confronted with my own vulnerable body made up of bone and fragile tissue, and at the same time witnessing the beauty of what remains. I imagined what it would be like to hold the bones of my beloved in my hands and to take paint to them as an act of cherishing and remembrance.

Two summers ago I was traveling in Austria and visited the tiny village of Hallstatt. Perched between a mountain and a lake, Hallstatt is best known for its early Celtic heritage and the treasures of ancient remains discovered there. But next to the Catholic Church is a tiny chapel, a bone chapel. You see, the cemetery is so small that bones had to be removed periodically to make room for the newly dead. The skulls were bleached in the sun and then lovingly hand-painted by family members with names, dates, and decorations. Standing in the room with 600 adorned skulls was a transcendent experience. I was brushing against my own mortality, confronted with my own vulnerable body made up of bone and fragile tissue, and at the same time witnessing the beauty of what remains. I imagined what it would be like to hold the bones of my beloved in my hands and to take paint to them as an act of cherishing and remembrance.

While traveling across Europe, I discovered that many of the churches and cathedrals have skulls carved from marble scattered through the building. I appreciated those reminders of mortality, the skulls dwelling in the sacred space alongside winged angels. I especially loved the skull with the Bishop's mitre, a reminder that no one is spared death.

When my mother died, I was with her the last five days or her life and even there at the moment of her final breath. My most visceral memory is massaging her limbs with hospital lotion as she lay unconscious and we waited for her to die. I was so intimate with death in that room, blessing me and wounding me in the same thrust. I lost my fear of death and bodies no longer living because of the excruciating holiness of that time.

St. Benedict wrote in his Rule to "keep death daily before your eyes." He knew that life was so profoundly precious that we needed to stay rooted in our own mortality so we might remember to cherish our moments. Helen Nottage (http://www.helennottageceramics.co.uk/index.htm) is a young ceramicist in England who creates sculptures of the human form in varying stages of decay. At an earlier time in my life I would have been repulsed by these images, but now I look on her images in wonder, finding beauty in her careful attention to the details of the body decaying. They make me uncomfortable too, knowing this will be me one day. Yet in following St. Benedict's sage advice, confronting my own death does not fill me with fear. It makes me cleave to my life, plunging me into the wonder of this moment. I pull my husband closer, I make certain to hug my friends, I am grateful for each day as gift.

We are always in a process of decay, something our culture urges us to resist at every possible turn. Just like the waning of the moon, the season of autumn, and the luminous threshold when day descends into night, we are invited to embrace the beauty of our entire human reality, the dying and the living, the dark and light, the falling apart and becoming whole again.

We are always in a process of decay, something our culture urges us to resist at every possible turn. Just like the waning of the moon, the season of autumn, and the luminous threshold when day descends into night, we are invited to embrace the beauty of our entire human reality, the dying and the living, the dark and light, the falling apart and becoming whole again.

Theologian James Nelson writes: "Our human sexuality is a language as we are both called and given permission to become body-words of love. Indeed our sexuality-in its fullest and richest sense-is both the physiological and psychological grounding of our capacity to love."

Body-words of love. That phrase takes my breath away. How do I allow my very body to become the fullest expression of love and tenderness in the world? This body with its aches and its loveliness. This body that will one day become dust, but also sprang from my mother in a burst of desire for life. In all this attention we give to the perfection of the body, we undermine our capacity to become body-words of love. We forget that we are called to the joy and the sorrow woven together. No surgery can excise our mortality. No procedure can remind us of our sheer giftedness, gift given to each other. The effect of our obsessions with our bodies is that we grow in our distrust of our physical selves. We are not offered ways to be with our bodies in the full range of their glorious beings - the joys, delights, pain, and disappointments. We are not encouraged to trust our bodies in this culture, for they forever need improving. We can buy an endless variety of products and programs geared solely at responding to the message that our bodies are somehow not good enough, not beautiful enough, not wise enough on their own.