The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara(2003)

Today's documentary filmmakers are the modern-day prophets, naming the inconvenient truths our society would rather not face. More than anything else, the ‘aughts could be seen as the decade of the documentary. The combination of affordable digital cameras and editing software gave the keys to the kingdom to a new generation of young filmmakers. One of the best films about the current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan was most effective because it was not specifically about the current wars, and that's the 2004 Academy Award winner for Best Documentary: The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara. McNamara is cagey and candid as he answers questions about the wars (World War II and Vietnam) that he shaped-and shaped him. Still, like Pilate in the gospels, he asks the best questions: "Was killing a hundred thousand people in Tokyo in one night moral if it helped us win the war?" "What makes it immoral if you win, but not immoral if you lose?" "How much evil is permissible to be done in the service of good?"

Today's documentary filmmakers are the modern-day prophets, naming the inconvenient truths our society would rather not face. More than anything else, the ‘aughts could be seen as the decade of the documentary. The combination of affordable digital cameras and editing software gave the keys to the kingdom to a new generation of young filmmakers. One of the best films about the current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan was most effective because it was not specifically about the current wars, and that's the 2004 Academy Award winner for Best Documentary: The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara. McNamara is cagey and candid as he answers questions about the wars (World War II and Vietnam) that he shaped-and shaped him. Still, like Pilate in the gospels, he asks the best questions: "Was killing a hundred thousand people in Tokyo in one night moral if it helped us win the war?" "What makes it immoral if you win, but not immoral if you lose?" "How much evil is permissible to be done in the service of good?"

Dogville (2003)

Lars von Trier's films do nothing if not inspire impassioned responses, angry disapproval from his staunchest critics and lofty praise from his most ardent supporters. Dogville is no exception. This is the sad tale of the township of Dogville, in the Rocky Mountains, and the seemingly good, honest folk that live there. One day, a mysterious woman, Grace (Nicole Kidman) arrives seeking refuge from pursuing gangsters. The film follows the townspeople's decision to hide her and their increased demands on her in exchange for their "protection." Dogville reveals the hypocrisy and violence that often lies behind small town religious fundamentalism and "hospitality." Yes, it's over-the-top, and perhaps unfair, but there are nuggets of truth to this tale that anyone who has ever lived in a small town will quickly recognize.

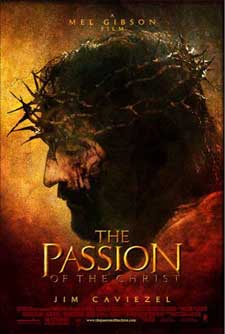

The Passion of the Christ(2004)

Like The Birth of a Nation (1915), a film soinfluential, and problematic, it can't be ignored. Owing as much to Hollywood horror as the Bible, the film presents Christ as a kind of he-man, whose primary characteristic seems to be his ability to endure super-human amounts of pain brought about by increasingly exquisite devices of torture. I've been admonished in my objections to the film by Catholic friends who remind me about the importance of suffering in Catholic theology, as well as the film's affinity for people who have suffered poverty or torture at the hands of corrupt governments. And yet, Gibson is not proposing a work of liberation theology. This film, produced by this wealthy/flawed/addicted director, reveals a childish, stunted theology: namely, in order for the atoning sacrifice to "count," Jesus had to suffer super-human feats of agony, more physical pain than anyone else in history. Jesus died so we wouldn't have to see a film like this.

Like The Birth of a Nation (1915), a film soinfluential, and problematic, it can't be ignored. Owing as much to Hollywood horror as the Bible, the film presents Christ as a kind of he-man, whose primary characteristic seems to be his ability to endure super-human amounts of pain brought about by increasingly exquisite devices of torture. I've been admonished in my objections to the film by Catholic friends who remind me about the importance of suffering in Catholic theology, as well as the film's affinity for people who have suffered poverty or torture at the hands of corrupt governments. And yet, Gibson is not proposing a work of liberation theology. This film, produced by this wealthy/flawed/addicted director, reveals a childish, stunted theology: namely, in order for the atoning sacrifice to "count," Jesus had to suffer super-human feats of agony, more physical pain than anyone else in history. Jesus died so we wouldn't have to see a film like this.

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (2005)

Directed by Tommy Lee Jones, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada proved his worth both behind the camera and in front of it as well. In his directorial debut, Jones uses the borderland of Texas and Mexico as a palette on which he paints a critique of the "American dream," commentary on immigration, and an imaginative view of forgiveness and reconciliation so desperately needed in both these issues. By walking this imaginative path to forgiveness, this film shows, in one way, how we as a society may break the cycles of violence that enslave us. The Three Burials tells the story of two friends, Pete Perkins (an American) and Melquiades Estrada (an illegal Mexican immigrant), both of whom work on a cattle ranch in Texas. They form a fast friendship that culminates in Pete's promise to Melquiades to bury him in Mexico if something ever happens to him. Unfortunately, their friendship is tragically broken when Mike Norton, a rookie border patrolmen, accidentally shoots and kills Melquiades, forcing Pete to uphold his promise. Jones flashes back and forth between scenes around Melquiades' death and scenes of his friendship with Pete for the first part of the film. The majority of the film, however, follows Pete's journey back to Mexico to bury his best friend, a journey full of rich theological and spiritual implications that echo theologian Marjorie Suchocki's notions of forgiveness as the act of willing the well-being of the offender.