By Andrew Tatusko

This is Part II in an on-going series on The Changing Church. Read Part I here.

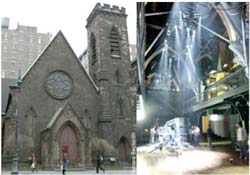

You know the line from the film Field of Dreams: "Build it and they will come." Unfortunately, that has not been the case in American mainline Protestant churches. Membership and attendance have been declining for several decades now since an attendance bubble in the 1950s. In the mid 20th century, institutional Christianity dovetailed with politics against atheistic communism. The rebellion against institutions in the mid-60s and later only worked against an already weak set of conditions for sustainability, much less growth. Some will point to theological problems for decline, such as the growth of theological liberalism. Are these true claims? When we look at the issue through more sociological lenses, the reasons for the decline may be quite surprising.

You know the line from the film Field of Dreams: "Build it and they will come." Unfortunately, that has not been the case in American mainline Protestant churches. Membership and attendance have been declining for several decades now since an attendance bubble in the 1950s. In the mid 20th century, institutional Christianity dovetailed with politics against atheistic communism. The rebellion against institutions in the mid-60s and later only worked against an already weak set of conditions for sustainability, much less growth. Some will point to theological problems for decline, such as the growth of theological liberalism. Are these true claims? When we look at the issue through more sociological lenses, the reasons for the decline may be quite surprising.

Baptism, Confirmation, Marriage

Baptism, confirmation, and marriage are three key life-cycle components in how churches create social structures to support people as they grow up. If a church practices infant baptism, confirmation typically happens in early adolescence. If adult or believers' baptisms, this happens when other denominations perform confirmations. It resembles when Jewish bar mitzvah and bat-mitzvah rituals take place. Baptism and confirmation were rituals that functioned to incorporate children fully into the church as well as a transition into adulthood. That cycle does not work well anymore.

This cycle worked when people lived until their 60s and young adulthood, by necessity, started younger. When young adulthood started younger and ended younger, marriage also happened earlier, followed by earlier child-rearing, which is also symbolic of adulthood. But it does not function as well when people are living longer, up to their mid to late 80s or 90s. Colleges, with a few exceptions, have abandoned the notion of in loco parentis and have focused on developing people to be productive workers rather than upstanding adult citizens. This leaves still-adolescent kids alone to develop as they see fit without any real "training" to be adults. Young adults then transition into a career after college and get married around age 27. Child-rearing follows only a year or two after that. As these life cycles extend, it also means that transience and the lack of desire to become "settled" increases.

Where is the church in the young adult life cycle? The mainline institutional church is probably waiting for young adults to come back home, which could be expected in the pre-WWII days before 1940. But left to their own devices for a good 10-15 years, young adults may not learn to value religion as a core institution in their lives. Often the clearest and most integrated religious outlets on college campuses are campus ministries and para-church groups rather than the mainline denominational presence (with the exception of denominational colleges in some cases). When these factors converge, young adults may kiss the home congregation good-bye. In that stretch of time, religion in the institutional sense has become one more option for individual fulfillment and spiritual wholeness among a host of other options.

Mobility

Once young adults leave college or decide to start pursuing a career earlier, they tend to move around much more than ever due to how corporations treat employees at the lower ranks as expendable workforce. To "move up" anymore, it is rare to stay with the same company. The sense of shared loyalty between company and employee is not the same as is was earlier in our country's history. As boundaries and capital flows change in volatile global economic systems, people's social locations change in order to seek more stability. That stability is likely to happen sometime when your kids are growing up, if stability is even what you want at that time!

As young adults move around and engage in more transient social bonds, they will ''shop" for a church that more or less fits their own self-created idea of how religion shapes personal spirituality and "wholeness." They might start with the denomination like the one in which they grew up, but it's not a given that they will return to it. The church that young adults will continue to attend will likely have been the one to foster the strongest set of social connections to help them feel more embedded in a community. It will also be the one that is most flexible to changing demographics of people who are engaging in religious "shopping" behavior.