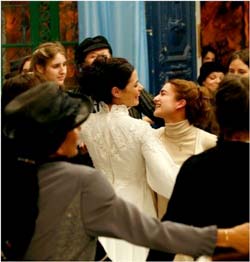

A conflict of personalities between the reserved Naomi and the extrovert Michal seems inevitable, but their relationship undergoes a radical transformation when both students are asked by the seminary's headmistress to deliver food to Anouk, played by the veteran French actress Fanny Ardant. As Naomi and Michal soon discover, Anouk was imprisoned for murdering her lover and now, terminally ill, looks for God's forgiveness. Michal talks Naomi into finding a kabbalistic Tikkun for Anouk; unable to find one in the Jewish sources, Naomi develops her own Tikkun. As they go through the different rituals of the Tikkun, their hostility transforms into friendship and then, into a love affair. Now, they have to face their true selves and decide whether and how to realize their homosexuality within the framework of their religious commitments.

A conflict of personalities between the reserved Naomi and the extrovert Michal seems inevitable, but their relationship undergoes a radical transformation when both students are asked by the seminary's headmistress to deliver food to Anouk, played by the veteran French actress Fanny Ardant. As Naomi and Michal soon discover, Anouk was imprisoned for murdering her lover and now, terminally ill, looks for God's forgiveness. Michal talks Naomi into finding a kabbalistic Tikkun for Anouk; unable to find one in the Jewish sources, Naomi develops her own Tikkun. As they go through the different rituals of the Tikkun, their hostility transforms into friendship and then, into a love affair. Now, they have to face their true selves and decide whether and how to realize their homosexuality within the framework of their religious commitments.

Nesher's film seeks to portray the struggle of ultra-orthodox women to assert themselves within a strictly paternalistic and chauvinist religious framework. The seminary provides an institutional setting, not liked but tolerated by the bigoted, ultra-orthodox establishment, where women can hone their intellectual capacities and nourish their dream to be treated someday as equal to men. To that end, it is the headmistress' explicit wish to bring up the first orthodox woman rabbi. However, it is the desires that such ambitions set in motion that compel. Indeed, in The Secrets, the seminarians' intellectual self-discovery is inherently linked to their ability to take pleasure in and express their sexuality. Thus, it is not enough that two protagonists recognize and attempt to undo the strictures foisted upon on them by their faith. Rather, they have to shed these fetters, to undress, both figuratively and literally, while the film turns into a performance of this striptease.

The Secrets' beautiful soundtrack plays a crucial role in prefiguring the unveiling of its characters' sexuality and intimacies. Defying the Talmudic ban on the female voice, the film's soundtrack is composed of liturgical pieces sung by women. Several sensual scenes linger on the women seminarians gripped by the singing of liturgical songs. Yet, as long as their desire is only expressed by their voices, it remains figurative and, hence, does not break the misogynist framework of halakha, even if it challenges it.

Michal and Naomi, however, go beyond the figurative into the literal. In a central scene, the two take Anouk to perform a purification ritual at a mikvah, a religious bath. As the three undress and enter the water facing each other, the camera focuses on Naomi and Michal's young nude bodies, but shows Anouk only from the shoulders up. Rather than comment on the tension between religious observance and sexuality, between the young and the aging body, or on the very meaning of transgression performed by the two young women, the scene elides this by narrating a moment of pleasure and gratification. The question becomes, for the two protagonists as well as for the viewer, whether such pleasure and gratification can or cannot be had within a halakhic framework.

As a story, The Secrets is not unlike the Avi Nesher's previous film Turn Left at the End of the World (2004), which tells of new immigrants who arrive at the southern Israeli development town of Mitzpe Ramon and try to adjust to their new life in Israel. Both films follow the friendship of two young women as they wrestle with the strictures put on them by their respective paternalistic, male chauvinist communities. In both, the discovery and realization of female sexuality is employed to shed light on the oppression of women. The initial presentations of this sexuality seem to claim to undermine, even explode, paternalistic values (though we might ask in what ways these values are truly challenged at the conclusion of each film). Finally, in both stories, a reserved woman ends up mounting much more of a challenge to these values than the extrovert.

As a story, The Secrets is not unlike the Avi Nesher's previous film Turn Left at the End of the World (2004), which tells of new immigrants who arrive at the southern Israeli development town of Mitzpe Ramon and try to adjust to their new life in Israel. Both films follow the friendship of two young women as they wrestle with the strictures put on them by their respective paternalistic, male chauvinist communities. In both, the discovery and realization of female sexuality is employed to shed light on the oppression of women. The initial presentations of this sexuality seem to claim to undermine, even explode, paternalistic values (though we might ask in what ways these values are truly challenged at the conclusion of each film). Finally, in both stories, a reserved woman ends up mounting much more of a challenge to these values than the extrovert.

Such sexual rebellion comes naturally for the characters in Turn Left at the End of the World and to the young women who dream of leaving their small town for the liberal culture and ethos of Tel Aviv. It seems, on the other hand, misplaced in the world of Jewish ultra-orthodoxy The Secrets presumes to portray, a world closed to Israeli secularism. Rather than endeavor to explore the terms in which sexuality may be experienced through the rejection of such liberalism, Nesher's The Secrets prefers the easy solution of, once again, setting a schematic, binary world, in which only secular culture could ensure sexual happiness and contentment.

This article was first published at Zeek, a Patheos Partner, and is reprinted with permission.

Shai Ginsburg teaches Israeli culture at Duke University, North Carolina. He has published articles on Israeli literature, culture, and history. He formerly reviewed films for Tikkun.