By Philip Clayton

In the New York Times Science section recently, scientists weighed in on the question of whether Francis Collins is fit to lead the National Institutes of Health. Can a man who reports a conversion experience to Christianity be qualified to lead America's top institutes for medical research? Some say no. Physicist Robert L. Park, frequent critic of "voodoo science," insisted that Collins' conversion was no more than a "hormonal rush" with no higher meaning.

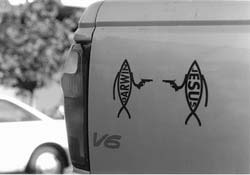

By and large, however, the criticisms of the new NIH director have been muted. The reason: Collins is not "soft on evolution." He is an unapologetic defender of the Darwinian consensus. What makes this criterion so important? And why do some biologists (the so-called "New Atheists," led by their enfant terrible, Richard Dawkins) now seem to believe it's not enough?

Of course, there were always scientists who claimed that there is no room for God after Darwin. But the religicide option in the evolution wars really gained momentum over the last decade or so in response to the widespread popular support of the "intelligent design" (ID) movement. Massive numbers of Americans now endorse the ID claim that cellular structures such as hemoglobin are "irreducibly complex," which means that evolutionary biology cannot explain them, even in principle.

Such assertions represent a double attack on science: they attempt to remove core biological phenomena from the reach of biology, and they claim that theories about an Intelligent Designer represent better science than the natural sciences can ever offer. Several polls show that over 50 percent of Americans affirm ID in this sense.

Scientists, sensing that the very institution of science was at stake, fired back with everything they had. Dawkins' massively successful The God Delusion has sold over 1.5 million copies; some are claiming that it has "mainstreamed atheism" for the first time in American history.

For the contenders, the stakes are ultimate: the very existence of God on the one side, the very existence of science on the other. Is it any wonder that reasoned debates -- discussions that acknowledge common ground -- are almost nonexistent? When we ran the global "Science and the Spiritual Quest" program just a decade ago, many leading scientists took moderate views. Religion did not need to be destroyed, they told us, as long as the basic conditions for doing science were not undercut. Theologians and religious leaders responded in kind: religionists have every reason to support scientific research and to learn from its results.

You'll have to look long and hard in the public-square discussion today to find similar bilateral calls for complementarity and partnership. Yet why should the relations between evolution and creation constitute a zero-sum game?

A moment's reflection reveals multiple ways in which these two great products of the human spirit can be distinguished: religion asks about the why, science explains the how; science researches matters of empirical fact, while religion is concerned with matters of ultimate values; scientists use empirical techniques and theories to account for the physical and natural world, whereas religionists are concerned with the metaphysical and the supernatural; science studies how the heavens go, religion how to go to heaven.

One does not need to find all these formulations adequate (I, for one, do not) in order to doubt that science demands the death of religion or religion the death of science. Here's the point: only when one affirms some sort of "live and let live" policy is it possible even to begin a serious discussion about evolutionary biology and (say) belief in God.

When evolutionary and religious explanations are construed as fighting for the same territory, they will unleash their weapons upon each other -- as today's religion wars show. When we recognize and acknowledge their different strengths, a far more interesting discussion emerges.

This new debate is challenging because it requires both sides to give up certain hegemonic claims: scientists, the claim that science provides the answer to all metaphysical questions; and religionists, the claim that they know better than science how nature works. Yet a whole series of fascinating questions arises when hegemony is off the table: is there a directionality to evolution or is it, as Stephen Jay Gould thought, a "drunkard's walk"? Do the emergent worlds of culture, ideas, philosophy, art, and even religion make any irreducible contributions to explaining what it is to be human? How (if at all) could a divine influence on cosmic history be compatible with the scientific study of the cosmos? What kind of influence would it have it be? Will humans respond more appropriately to the global climate crisis when scientific data are combined with religious values and motivations for action?