By Talia Davis

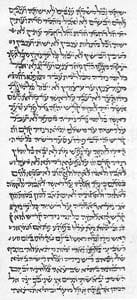

The parsha (weekly Torah portion) for the week ending May 22 is Naso. Naso means "lift up" in Hebrew and is the sixth word (and first distinctive word) in the portion. It also happens to be the longest parsha in our cycle. 176 verses, whew! Be sure to check out the cartoons at the end for some great perspectives on these Torah portions.

Meet the Joe Shmoe of the ancient days! But first, I must really remind you to check out the cartoon video at the end of the parsha. This one is very, very good.

Okay, before we meet Joe, we have some numbers and duties to take care of first. The parsha picks up where we left off in Bamidbar. G-d tells Moshe to count the Gershonites (of the tribe of Levi) who were of age to serve in the Tabernacle (between ages 30 and 50). He also had to count the Merarites and Kohathites, all part of the Levite tribe, all with different jobs in the Tabernacle. Of the 22,300 descendants of Levi, there were 8,580 that were of age to work in the Tabernacle.

Next, G-d gives instructions about purifying the camp, removing sick people or people who have touched a corpse, and addressing the issue of remuneration after having wronged a fellow Jew. However, it is the next section, only 18 verses long, that gets most of the attention.

This is where the word Sotah ("wayward wife") comes into our vocabulary. Here's Mr. Shmoe. He is just a normal Israelite, trying to make his way through the desert and all of the sudden he gets jealous. Angry, he accuses his wife of infidelity. What follows is the ritual for determining whether a wife has been faithful or not. The ritual is pretty nasty and reminds me of the witch trials. Once accused, she has to stand before the community with her hair uncovered (a disgrace to a married woman), agree with the priest by saying Amen, and then is given the "water of bitterness" to drink. We aren't quite clear on what was in it except for one ingredient. The priest writes the curse down on paper then soaks it in the "water of bitterness" so the words rub off into the liquid. The woman was to drink it. If she were innocent, she would be fine. If guilty, her belly would become distended and she would be ill, unable to bear children.

As a modern woman, I can only wonder what was in that water. We know there was some earth from the floor of the Tabernacle and "sacred" water, but what else? Now, don't get me wrong. I love the Torah and my faith tradition, but there are clearly some things that disturb me. But here is the beautiful part of being Jewish. Nothing is ever how it seems. By 40 C.E., the death penalty for crimes was abolished and so people could confess without fear of death. The Mishnah says that this was not a preferred experience; rather they were brought to the Sanhedrin (Jewish court) first. They tried everything to get the woman to confess before doing this. Doesn't make me feel all warm and squishy inside because we know how many false accusations happen, but still. When the Talmud was finally finished, the "waters of bitterness" idea was just a threat to help confession, and by 70 C.E., Ben Zakkai and his Sanhedrin got rid of the method . . . some say since men were not above suspicion.

Whew! Eighteen verses, so much controversy! What happens next in this giant portion? Well, we talk about the Nazirites who want to set themselves aside for G-d (could be male or female). They couldn't drink wine (or even eat from things that came from a grape vine -- grapes, raisins, vinegar). They couldn't cut their hair or be near a dead person (even if it was family). You didn't have to be a Nazirite forever; you could choose a term and then go back to shaving and drinking. One famous example of a Nazirite is Samson. He was a Nazirite from birth as a result of his mother negotiating with an angel about her inability to conceive.