By Timothy Dalrymple

Congratulations on your new book, Humanitarian Jesus: Social Justice and the Cross. Can you tell us what you mean by "Humanitarian Jesus"?

Congratulations on your new book, Humanitarian Jesus: Social Justice and the Cross. Can you tell us what you mean by "Humanitarian Jesus"?

Thanks. What we mean by that term is that ever since Christ walked this earth people wanted to put labels on him -- prophet, rabbi, heretic, demon -- and in modern Christianity we tend to do the same. We want to place Christ in a box or define him by certain actions. Our idea for the title was to ask the question: Is it fair to consider Christ as a humanitarian, and, if so, what does that mean for us?

There's a term in the subtitle that has come under attack recently. What do you take "social justice" to mean? Is "social justice" specifically a Christian term? And should it be associated with "liberal" social policies?

Sure. That term has come under some recent attack from Glenn Beck and others who have read it as a liberal term that connotes wealth redistribution or a political socialist agenda. That reading is extreme and pulls it out of the greater context of its history. In fairness, the social gospel or social Christianity isn't anything new. The basic ideas were formed around the time of the industrial revolution in Europe as a reaction to very basic obvious human suffering. We talk about this in the book, but in the later 1800s, the church was isolated within its walls, both literally and metaphorically, and the world was suffering outside. People started to question why the church wasn't invested in the suffering of the people around the big issues of the industrial revolution. Is it really okay to step over a homeless starving person on the steps of a church building to go inside and worship God? The early call was to get outside and get invested. Over time that theory was adopted and expounded by more liberal agendas that stretched it outside of theology and Christianity into politics and general social theory, but that is not where it started and in our opinion is not where it belongs.

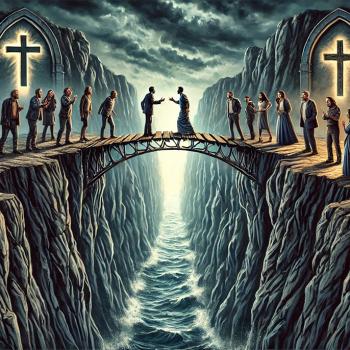

There is a difference between making a social investment for the sake of social investment and making it for the sake of the cross. There is a difference between doing social justice out of political or social theory and doing it because you believe it is part of your personal call to Christ and redemption. We wanted to bring the discussion back to the cross to look specifically at how Christ dealt with the issues in his life and teaching.

There has been a revitalized movement for social justice, especially amongst the younger generations. How should we understand the relationship between evangelistic and social justice ministries?

I think that is the basic issue facing this generation. We are coming out of an era where Christianity was defined by what we were against and now we are seeking to define it by what we are for. I think that is good, but I think it presents some problems, just as the prior era did, because it risks fractionalizing the Gospel into a bunch of independent parts. It becomes a sort of "choose your own adventure" type of faith where as long as you grab onto some part of the Christian message that is good and positive you are going in the right direction. As a result, I think younger evangelicals are gravitating to acts of kindness and love as a means of expressing their faith and perhaps starting to move away from the doctrines of sin and redemption that seem to be judgmental and divisive.

I don't think that is the right approach. The two issues are intimately related. Christ was evangelizing in every aspect of his life, whether he was speaking truth or meeting need. It was all part of who He was. I think understanding that we can't divide the issues is the start of reaching a personal perspective that honors our calling.

You interviewed many leading thinkers in the Christian ministry world today. What do you sense are the major trends in the social justice ministry today?

Excellence and relevance. Many of the leaders were interested in doing good work better by making that work relevant to every generation of Christians. I also think many of the ministries understand the risks that are facing them in this era. They understand that it is easy to be misread by outsiders or unfocused in what they are doing.

Were there any responses that really surprised you?

My interview with Isaac Shaw surprised me. Here is a man that grew up starving on the streets as an abandoned child in India and was so hungry that he ate newspaper to fill his stomach, yet he is totally opposed to feeding people without the Gospel being involved. He has very strong perspectives on how the church must be the center of the solution for Northern India. You might reject his position, but not because he doesn't have the life experience to understand suffering and need.