By Timothy Dalrymple

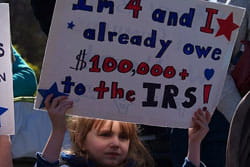

Every American who cares about the vitality of the American democratic experiment should strenuously object to the way in which the Tea Party movement has been systematically misrepresented and mocked across most major media. The Tea Party -- however one views the principles and personalities most associated with it -- is precisely the kind of citizen accountability our founders envisioned and our form of government requires. Democracy holds the governing class accountable to the governed, and the Tea Party movement is a clear example of the governed standing athwart the will of the governors and shouting Stop.

Every American who cares about the vitality of the American democratic experiment should strenuously object to the way in which the Tea Party movement has been systematically misrepresented and mocked across most major media. The Tea Party -- however one views the principles and personalities most associated with it -- is precisely the kind of citizen accountability our founders envisioned and our form of government requires. Democracy holds the governing class accountable to the governed, and the Tea Party movement is a clear example of the governed standing athwart the will of the governors and shouting Stop.

I began this series on the Tea Party (the first part is here) not because I agree with every sentiment expressed on the protest placards or over the microphones (I agree with some and not others), but because the cultured despisers of the movement are perpetrating a collective character assassination the likes of which I have never seen in my lifetime. The grass roots, to be sure, are never finely manicured. Popular political movements do not move gracefully. Yet even the most admirable political movements now praised in our history books had their own unsavory elements. Such is the rowdy raw material of democratic progress. If ordinary citizens cannot band together and protest the actions of their government without being slandered as rampaging paranoiacs and selfish, slavering, knuckle-dragging racists, then sooner or later ordinary citizens will no longer band together at all -- and our country will be the worse for it.

Among the many who have caricatured the Tea Party movement, the most disappointing, to me, have been progressive Christians. Reverend Jim Wallis, arguably the most influential progressive Christian activist in Washington, founder and editor of Sojourners and friend to President Obama, Bono, and various other world leaders, recently wrote an article entitled "How Christian is Tea Party Libertarianism?" His answer -- that it is not Christian at all -- will hardly surprise anyone who knows Jim Wallis.

I should note, in the interest of full disclosure, that I do know Jim Wallis. I was a teaching assistant for a course he taught at Harvard University. I have nothing negative to say about Reverend Wallis' conduct and character; he was always kind and generous with his students and teaching assistants. Whatever his critics might imagine, Wallis is neither a celebrity-chasing political opportunist nor a cynical Democratic party operative. His views on some social issues, such as abortion, are moderate. However, on the issues that matter most to him, the issues to which he devotes the vast proportion of his time and effort, Wallis is a true-blue liberal. That he believes wholeheartedly in what he does is admirable, yet it makes it difficult for him to see clearly the merits of the opposing side of the argument, and difficult to resist the temptation to damage the opposition through misrepresentation rather than portray their beliefs as charitably and honestly as he should.

To borrow a more inflammatory phrase from George Will, Reverend Wallis becomes, when describing conservative Christians and conservative policy preferences, "a pyromaniac in a field of straw men." His argument against the Tea Party is a sterling example. Wallis felt caricatured when Glenn Beck reduced his vision of social justice to "forced redistribution of wealth, with a hostility to individual property." As Wallis wrote, "virtually no church in America, or the world, would support anything close to that as a definition of social justice." Yet Wallis himself is guilty of caricature. Virtually no Tea Party supporter would accept anything close to his definition of their movement.

–

The first sleight of hand comes in the phase, "Tea Party Libertarianism." Wallis poses the question: "Just how Christian is the Tea Party movement -- and the Libertarian political philosophy that lies behind it?" Yet not all Tea Party supporters are Libertarians, and Wallis twists the Libertarian "political philosophy" beyond recognition. It is better to think of libertarianism and statism as two warring political impulses. All agree that some amount of government intrusion is necessary to maintain order, protect the innocent, and defend the homeland. All likewise agree that some amount of government limitation is necessary in order to constrain government powers, protect private enterprise and preserve individual rights and freedoms. Tea Party supporters are convinced that we have gone too far in the statist direction, and thus there is need for a libertarian impulse to limit government powers. This does not make them Libertarians in the classical sense, and certainly not in the extreme sense that Wallis describes.