By Gary Gach

All of us observe rituals in our daily life. It might be as unconscious as stopping at street intersections. Or putting our keys or glasses in the same place. Such rites can bring order and harmony to life's seeming chaos.

All of us observe rituals in our daily life. It might be as unconscious as stopping at street intersections. Or putting our keys or glasses in the same place. Such rites can bring order and harmony to life's seeming chaos.

Some rites can bring us closer to the divine. As in prayer. Keeping a home altar. Or a regular quiet walk in nature. Or carrying a small book in your purse or pocket.

Here's where a spiritual tradition can come into play: in providing us with vehicles for appropriate ritual. Whatever your path, you might glean a couple of interesting insights through exploring the roles that rites can play in the practice of Buddhism.

For instance, when do rites become too rigid? How to know if rites work? How deep can rites go?

Vitalizing the spirit as well as the letter of the law

One way to consider ritual is negatively, when it becomes a hair shirt. There are times in the life of any tradition when it can get calcified, or abstract. In such case, a new tradition arises, in counterbalance -- such as Zen in Buddhism, Hassidism in Judaism, Sufism in Islam.

Here's an example of Zen. I remember sitting with a few dozen people one night, listening to Japanese Zen master Shunryu Suzuki Roshi deliver a talk. This was decades ago. There were more Buddhas sitting behind glass cases in museums than living Buddhas offering teachings.

Anyway, mid-way in his talk, he mentioned that when he goes to the bathroom to pee he claps his hands three times first. He then smiled, looked at us all, and added, "Of course, I'm just making this up. The point is, that some of you believe me when I say this."

What he was telling us was no different than what the Buddha had said: "See for yourself." Adopt in our practice only what we have tasted and tested for ourselves, and found to be nourishing, whether or not it's attributed to the Buddha or a famous teacher, or found in a book or on a website (even Patheos). In a sense, it's DIY, do-it-yourself. Even if the Buddha himself calls to us, we still have to take the call. Even that's not enough: we also have to put down the phone and put the call into practice, in our own lives.

What can resemble idolatry, to outsiders

Do you keep a photo of a loved one on your desk or in your wallet? A stranger see only a face, whereas to you the picture evokes deeper and deeper meaning over time. So it can be with rites. Those outside the circle do not understand the dance, while those inside . . . dance.

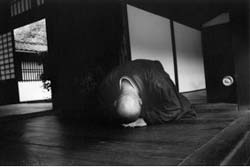

Consider this frequently misunderstood rite: bowing to statues of the Buddha. To outsiders, this can seem like a sacrilege. After all, a statue has no eyes with which to see, no ears to hear, etc., so bowing to one can run the risk of fetishism and idolatry. But the majority of practicing Westerners today will tell you an image of the Buddha is only a reminder of an experience. So this practice of bowing can be to water the seeds of our own awakening, the Buddha within; to remember our birth right, a genuine life of true happiness; to acknowledge our own Buddha nature.

(Bowing, in and of itself, may be universal: a ritual of becoming one with. Affirming the depth and grace of that unity. An interesting side note: Zen priest Norman Fischer noticed when he bowed to a Buddha, it would seem to bow back. So he chose a small statue for his daily reflection, because its smaller bow to him wouldn't seem as daunting.)

Buddhism is ultimately first person (only you know if it's hot or cold, so it's all up to you). So, too, is it also present tense. Real time. One doesn't perform a rite because it is so ("Simon says"). One does to make it so: discovering and actualizing its truth in the present moment of our lives. Each moment. Moment to moment.

So bowing, or wearing a ceremonial robe, or any rite can become a trap or be a door to liberation. It can be a form of sleep-walking, or an awakening. It's up to each of us, all the time.

The raft is not the shore; the path is the goal

Are rites means, not ends themselves? The Buddhist saying is, "The raft is not the shore." That is, when you reach the other shore, don't carry the raft along with you: tie the raft off at the shore before going on ahead. The raft was a vehicle.

Looking deeper, we can find advanced interpretations of the skillful use of expedient means (upaya, in Sanskrit). For instance, there's the idea that there are different means for different people, or different stages of reception. And, too, if we discover, in the end, that we're already on what seemed the other shore and have been so all along, then too we might appreciate the tools' awakened value, in and of themselves.