That fragile sense of order was in danger of collapse after Hamas seized control of the Gaza Strip from Fatah, the mainstream wing of the Palestine Liberation Organization, and threatened to do the same in the West Bank. Yet there was little visible tension between the two factions in Hebron. The half dozen large Palestinian clans that comprise the core of the city's ruling elite have cooperated to tamp down internecine violence.

The other reason for the current quiet is the Israeli army, which constantly monitors militant groups and stages periodic raids for "wanted men" in both its own zone and in the larger Palestinian-ruled area. To the extent those operations help keep a lid on Hamas and prevent suicide attacks on Israel proper, local officials seem to tacitly accept them. There have been frequent reports in the Israeli press that, for the first time since 2000, Fatah and Israeli security chiefs are sharing information and seeking jointly to enforce order.

In fact, during my visit, Hebron was more stable than I'd seen it in decades. A recent headline in the Israeli daily Haaretz labeled the city, "The safest place in the territories."

Jamal Maraqa's small clothing, rug, and jewelry shop is located in the heart of the old souk. A soft-spoken man in baggy pants and a short-sleeved shirt, Maraqa comes from a distinguished family. On one wall of the shop he proudly displays snapshots of his father, a respected mediator of local disputes. Trained as a jewelry-maker in England, Maraqa returned to Hebron in the mid 1980s to open his shop.

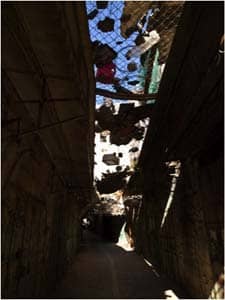

The old souk is a warren of alleyways and nooks dating back to the crusader era. There are vaulted ceilings and long stretches of small shops, broken by occasional courtyards with crumbling houses. But these days one of the most notable features is the chain-link netting that has been placed above the main passageways. It is there to prevent Jewish settlers in neighboring compounds from pelting market-goers with garbage. Rotting refuse piles up atop the netting.

Maraqa, whose shop is located just below the netting, says the market used to be the pride of Hebron and the entire southern half of the West Bank. But area residents long ago took their business elsewhere to avoid the prospect of confrontations with soldiers or settlers. In times of trouble, the army has shut down the business many times, imposed curfews on the area, and rounded up young Palestinian men. Tourism has dried up as well. Where the shop once made $3,000 to $4,000 per month in profits, Maraqa figures he's now down to between $500 and $1,000. Still, he's determined to stay.

Maraqa, whose shop is located just below the netting, says the market used to be the pride of Hebron and the entire southern half of the West Bank. But area residents long ago took their business elsewhere to avoid the prospect of confrontations with soldiers or settlers. In times of trouble, the army has shut down the business many times, imposed curfews on the area, and rounded up young Palestinian men. Tourism has dried up as well. Where the shop once made $3,000 to $4,000 per month in profits, Maraqa figures he's now down to between $500 and $1,000. Still, he's determined to stay.

"In a way, this is like a big prison and we're the prisoners," he says. "But this is my home and I won't leave. I've gotten used to it."

The silence here is in contrast to the northern part of the city, where the new Bravo Supermarket has just opened its doors. Hebron now seems like a city broken in two. One part throbs with people, vendors, and noise and boasts a sleek new 10-story insurance company building and bannered ads on the main streets touting school uniforms, wedding gowns, and Power Horse energy drinks. It's easy to see why Hebronites boast of their city as the economic engine of the West Bank, responsible for generating some 30 percent of its income.

The south sector, including parts of the center and the old souk, seems like a ghost town under Israeli military control. Once makeshift army checkpoints are now fortified by concrete towers. The old bus depot and two gas stations have been dismantled. Moreover, the trailers at the top of Tel Rumeida now look permanent -- there's landscaping and a concrete playground out front. Above them on the hill is a three-story Jewish yeshiva constructed almost a decade ago and named for a rabbi who was stabbed to death in his home nearby.

Two Israeli human rights groups -- Btselem and the Association for Civil Rights in Israel -- reported last May that 1,014 Palestinian housing units are vacant, representing 42 percent of homes in the once-bustling area. Some 1,800 business establishments -- 75 percent of the total -- are also shut down, and the army has established 102 roadblocks and checkpoints. The report laid the blame squarely on the settlers and the army, citing severe restrictions on Palestinian pedestrians and vehicles, military-enforced shutdowns, and the failure of the authorities to enforce the law against settlers who assault Palestinians and their property. "These restrictions, prohibitions and omissions have expropriated the City Center from its Palestinian residents and destroyed it economically," the report concludes.