Indeed, the child is often the last thing the parent (or parents) thinks about. Many people have become comfortable with the idea of using and discarding embryos in stem-cell research, and, since abortion is legal, many don’t think child deserves protection until the moment he’s left the womb.

Despite all this, many still find something troubling when they hear, as we did this past June, that a number of women who attempt to conceive through IVF choose to abort the very baby they tried to conceive. When we protect babies that are wanted by their mothers, but don’t protect those who are unwanted by their mothers, what do we do when a mother can’t make up her mind?

Despite all this, many still find something troubling when they hear, as we did this past June, that a number of women who attempt to conceive through IVF choose to abort the very baby they tried to conceive. When we protect babies that are wanted by their mothers, but don’t protect those who are unwanted by their mothers, what do we do when a mother can’t make up her mind?

It’s complicated. Or is it? There’s reason to believe that the thinking on the protection of embryos may be shifting. Just this week, a U.S. district court ruled against federal funds going toward stem-cell research “in which an embryo is destroyed.”

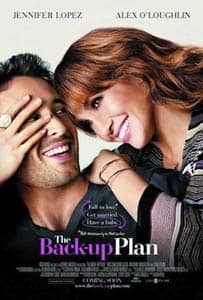

Yet, although artificial reproduction is a life-and-death issue, it is often painted in rosy hues, as a service to women helping make their dreams come true -- whether in embryo-donation ads, or in infertility-center ads, or in Celine Dion’s public statements, or in movies like The Switch and The Back-up Plan. The health risks are overlooked, partly out of desire to find a quick solution to infertility, and partly in the name of a philosophy that says a woman should be able to have a family however and whenever she wants.

In reality, artificial reproductive technology is no service to women; it’s not the quick and easy way to get pregnant that it’s promised to be, and it brings more hardships to infertile women along the way. Moreover, it doesn’t heal a woman’s infertility at all. As Dr. Anne Meilnik at the Gianna Center, a Catholic health-care center in New York, has said, it’s covering up the health problems that may be causing her infertility -- which can and should be treated -- by instead making a child with artificial technology.

For women like the characters Aniston and Lopez play in these recent films, artificial reproductive technology allows them to cover up personal problems that have led to their being single at forty. Lopez’s confidante in The Back-up Plan called her to task saying, you got a sperm donor because “he’s the perfect boyfriend right? He’ll never let you down”; to which Lopez replied, “No, I got a sperm donor because I wanted a baby. I wanted a family.”

In The Switch, Aniston’s artificially conceived child longs for family too. He saves empty photograph frames with stock photos still in place, pretending the men pictured are the father, his uncle, and his grandpa that he doesn’t have. There’s just something about family that cannot be created artificially -- a sad truth these films giggle past. Even a child whose father dies before he is born has a real family in a way the artificially conceived child never will.

The Waiting City, a recent Australian film that tells the difficult story of a couple seeking to adopt a child overseas, depicts the trials of infertility much more realistically. It’s far from a romantic comedy. And there are some deep aspects of the human experience -- the realization of one’s aging, the desire for love and family, and the sorrow of lost time -- that it comes much closer to reaching.

Resources:

- For more on the effects of IVF on women, see Cheryl Miller’s “Blogging Infertility” from The New Atlantis; on the women who donate their eggs, see the documentary Eggsploitation; and on the children conceived, see the New York Times article “Picture Emerging on Genetic Risks of IVF.”

- On women aborting their IVF-conceived children, see “A New Debate Over In Vitro.”

- For the recent district court decision, see “U.S. Court Rules Against Obama’s Stem Cell Policy.”

- The Gianna Center

- Elizabeth Marquardt’s “The Kids Are Not All Right”

- Ryan Anderson’s “Reproduction and Public Discourse”

Mary Rose Somarriba is the managing editor of First Things, where this article first appeared.