By Faith & Leadership

After the collapse of European colonialism in the last century, Christian missions has gone from a focus on partnership in the 1960s and ‘70s to a present-day desire for authentic relationships among Christians from differing cultures worldwide, said Dana Robert, a historian of world Christianity and missions.

After the collapse of European colonialism in the last century, Christian missions has gone from a focus on partnership in the 1960s and ‘70s to a present-day desire for authentic relationships among Christians from differing cultures worldwide, said Dana Robert, a historian of world Christianity and missions.

"People want to share the gospel," Robert said. "But they want to do it in what they see as a nonimperialistic way and to truly listen to another person -- walking in their shoes, learning their language, living as they live."

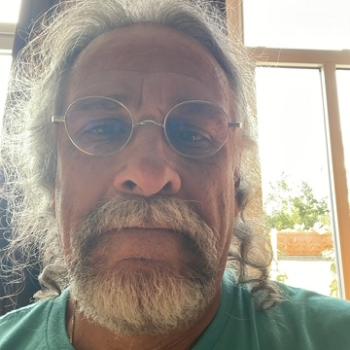

Robert is the Truman Collins Professor of World Christianity and History of Mission at Boston University School of Theology and co-director of the school's Center for Global Christianity and Mission. She has written several books, including her two most recent, Joy to the World! Mission in the Age of Global Christianity and Christian Mission: How Christianity Became a World Religion. Robert earned her bachelor's degree at Louisiana State University and her doctorate from Yale University.

Robert spoke with Faith & Leadership (a publication of Duke Divinity) about the impact of globalization on church missions. The video clip is an excerpt from the following edited transcript.

How has Christian mission changed over the last few generations?

We're in a completely different mission context than we were in the mid-20th century. Three-quarters of the world's Christians are from Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Starting in the mid-20th century, there was a feeling, after European colonialism, that missions should be multidirectional, from everywhere to everywhere, the whole church taking the whole gospel to the whole world.

With globalization, we've now got a matrix of movement in which mission is taking place. Mission is taking place through migration, for example, of people from Africa moving to Europe or to the United States, people from Latin America moving to the United States, people from the United States moving to Asia.

The emphasis is not as much on the professional missionary who is sent from one place to another for a lifetime. It's a much more free-flowing set of networked relationships. In addition to migration as a major factor in mission, globalization has allowed the local church to become its own mission-sending agency. Anybody who's got an onternet connection can now arrange a two-week mission trip for the youth in the church.

Christianity is a worldwide religion made up of people who used to be seen as the receivers of mission. They now see themselves as missionaries.

How will this impact the way institutions think in terms of mission?

Interest in mission is now bubbling up from the grass roots. The creativity that's flowing upward creates a state of chaos. It's much harder for a leader to stay on top of all of this, and the question is, should a leader try to control it? Our structures need to move from controlling structures to enabling structures. The issue for pastoral leaders today is to be listening and discerning where the movement is among your own people who are interested in mission, and then helping to shape that in productive directions.

Can you give us an example of an organization that is moving from a top-down structure to an enabling structure?

The United Methodist Church is what I know best. In the 1970s and ‘80s, the Board of Global Ministries was seen as and saw itself as in control of mission. Now, the Board of Global Ministries has redefined its role to be a place you can go for information. It still does resourcing for the full-time missionaries in the church. It also is trying to enable annual conferences that are doing their own volunteer mission training.

Building institutions like hospitals and schools was once a key part of missions, but today we seem to have lost a theology of why institutions are important. What does that history of institution building have to teach us?

There is a whole anti-institutional movement in missions, and if you were to take, say, the Perspectives course, which is a popular lay training course in a lot of churches, there was an analysis saying that, in effect, the mission-station approach was wrong; schools and hospitals are too top-heavy, and they're not helpful. And a lot of people in the evangelical world have been formed with that bias against institutions. The reality is, though, that they've had their educational and medical institutions that they could take for granted. And what we're seeing now is, after and during a huge period of church growth in Africa, for example, African Christians are calling for those institutions. So what you often see after the Christian movement grows, the next step is to grow in depth. And people want education. They want medical care. They want the kind of -- whether you want to call it institutions or talk about the functions of it -- they want the things that make life better, because the gospel is to share abundant life, to bring people to abundant life through Jesus Christ. So becoming a Christian must make a material difference in your life. That self-improvement becomes a fruit of the gospel. And I think in the West we have taken that for granted often. . . .