By Jonathan D. Fitzgerald

Note from Timothy Dalrymple: Amid allegations that politically conservative evangelicals have been guilty of America-worship, Patheos' Evangelical Portal invited Christians from across the political spectrum to a thorough and constructive dialogue over (1) what differentiates patriotism and idolatry, (2) what is the right relationship between faith and politics, and (3) whether conservative evangelicals today are indeed guilty of national idolatry.

Today we launch the series with one perspective from the Right -- with an article from bestselling author David Limbaugh, and one from the Left -- with the article below from Jonathan Fitzgerald, managing editor of Patrol magazine. Fitzgerald was among those who sounded the alarm over the "Restoring Honor" rally. Below, he takes up the second question and explains his view on the right relationship between faith and politics.

The United States is not a Christian nation. This might be harder for some readers to see, depending on where in the country they live. Growing up in New England, it was glaringly obvious. When I was a teenager, Christian concert organizers - youth pastors really - couldn't get a decent Christian band to come within a few hundred miles of Boston. I knew a lot of evangelicals like myself, but I knew a lot of Catholics too, and a bunch of non-practicing Catholics and non-Christians. I knew that the politics espoused by my pastor in the pulpit wouldn't fly outside of the walls of the warehouse that served as our church. I came to see these two worlds as separate. Surely my religious beliefs influenced my politics, but I knew I shouldn't bring these beliefs into the public square.

The United States is not a Christian nation. This might be harder for some readers to see, depending on where in the country they live. Growing up in New England, it was glaringly obvious. When I was a teenager, Christian concert organizers - youth pastors really - couldn't get a decent Christian band to come within a few hundred miles of Boston. I knew a lot of evangelicals like myself, but I knew a lot of Catholics too, and a bunch of non-practicing Catholics and non-Christians. I knew that the politics espoused by my pastor in the pulpit wouldn't fly outside of the walls of the warehouse that served as our church. I came to see these two worlds as separate. Surely my religious beliefs influenced my politics, but I knew I shouldn't bring these beliefs into the public square.

It turns out this is a pretty typical progressive stance when it comes to the intermingling of religion and politics; essentially, don't do it. I might have maintained this separation and gone through life with the misinformed view that I should never let my Christianity influence my political views had it not been for a powerful speech - nay, sermon - by a Christian leader whom I have since come to respect deeply.

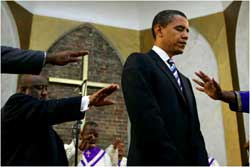

On June 28, 2006, then-Senator Barack Obama gave the keynote address at the Call to Renewal Conference sponsored by Sojourners in Washington DC. In the forty-minute speech, Obama showed a deep understanding of the problems and stigmas that surround the relationship between religion and politics in contemporary public discourse. He shared his own testimony and outlined ways by which the non-religious and religious could engage in productive dialogue about political issues.

In a story from his 2004 campaign for Senator of Illinois, Obama recalled how his rival, Alan Keyes, accused him of behaving "in a way that it is inconceivable for Christ to have behaved." Obama held views that Keyes believed to be in opposition to Christianity, and therefore he summarily dismissed Obama's faith. Though Obama answered these accusations with what he said "has come to be the typically liberal response in such debates...we live in a pluralistic society...I can't impose my own religious views on another," he felt that he had not fully represented his beliefs on the matter. Ultimately, he knew that his "answer did not adequately address the role my faith has in guiding my own values and my own beliefs."

Thus Obama set out, in 2006, to give the answer that he should have given in 2004. In much the same way that he so eloquently and thoroughly answered the nagging race questions raised during his presidential campaign with what has come to be called, simply, "Obama's speech on race," his Call to Renewal speech serves, I believe, as a template for a healthy mix of politics and religion.

After stating in no uncertain terms that secularists are wrong to ask religious people to leave their beliefs "at the door before entering into the public square," the remainder of his speech outlined three important facets of the relationship between faith and politics.

He began by affirming the importance of the separation between church and state in insuring, not only that the government of the people does not become a theocracy, but also, more relevant to the founding father's intentions, that the practice of religion is not dictated by the government. In so doing, the first myth that must be surrendered is the claim that the United States is a Christian nation. "We are no longer just a Christian nation," he said. "We are also a Jewish nation, a Muslim nation, a Buddhist nation, a Hindu nation, and a nation of nonbelievers." He further illustrated the religious diversity in this country by positing the hypothetical situation in which there were no other adherents of other religions in the US, only Christians, and asking then, "whose Christianity would we teach in the schools?"