By Monica A. Coleman

One of America's protective freedoms lies in the principle of "the separation of church and state." My friends who are legal scholars tell me that the provision was initially made to protect churches from the government. This "freedom of religion" means that the government will not persecute anyone for practicing her faith. It also means that the government will not coerce us all into practicing the same faith. This principle means that there are no government agents taking notes in our churches on Sundays, synagogues on Saturdays, mosques on Fridays, etc.

One of America's protective freedoms lies in the principle of "the separation of church and state." My friends who are legal scholars tell me that the provision was initially made to protect churches from the government. This "freedom of religion" means that the government will not persecute anyone for practicing her faith. It also means that the government will not coerce us all into practicing the same faith. This principle means that there are no government agents taking notes in our churches on Sundays, synagogues on Saturdays, mosques on Fridays, etc.

Sometimes, of course, we need to protect the government from religion. We need to ensure that arguments based on religious perspectives do not become the basis for our common laws. Rather our laws should be based on the shared values of equality, freedom, justice, liberty, and that important but slippery phrase, "the pursuit of happiness."

Over and over again, we see how difficult it is.

It is difficult it is to separate religion and politics.

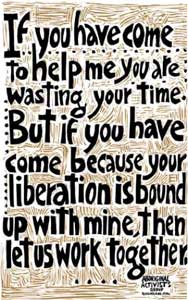

The field of liberation theology asserts that religious faith leads to political activism in the interest of justice. Liberation theology is an umbrella term of various theological expressions that situate the experiences of society's marginalized with the principles in religious texts that assert that we should treat each other the way we want to be treated, that God cares about the experiences of the outcast and downtrodden, and that our care for the oppressed in our midst reflects our love and devotion for God.

While this need not be a Christian principle, formal articulation of liberation theology was birthed in the late 1960s by Gustavo Gutierrez in Peru and James H. Cone in the United States. Gutierrez was living and working among the poor in Latin America. Cone was considering the experiences of African Americans in the midst of the overturn of Jim Crowism, assassinations, riots, the civil rights movement, and affirmation of self-love (black power). They both felt that the majority expressions of Christianity overlooked the Christianity that they read about in the gospels:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised. ~ Luke 4:18

I tell you the truth, whatever you did for one of the least of these, you did for me. ~ Matthew 25:40

They concluded that God has a preferential option for the poor (Gutierrez), and that God is on the side of the oppressed (Cone).

In the last forty years, these ideas have developed into some pretty sophisticated and important theological movements including Latin American, black, feminist, womanist, ecological, disability, and gay theologies. This is not an exhaustive list.

I recently spoke on this topic on NPR's "Air Talk" where Larry Mantle interviewed me.

I have a lot of academic and historical reasons for calling myself a liberation theologian, but there are also intensely personal reasons as well. My faith motivates me to fight for justice. My religion inspires me to speak out for those who are often silenced or ignored. My relationship with God tells me that a primary form of worship involves standing against stigma, torture, and lack of equality. Sometimes that means I stand with governments who are doing the right thing. Often, it means standing against a powerful majority. That powerful majority can be found in groups of people or in institutions that wield power in oppressive ways.

I don't do this because I belong to one political party or another. While that motivates many humanists toward social justice, it would not be adequate motivation for me. I do this because it's what I believe in the depths of my spiritual understanding.

This is important because one common critique of liberation theology is that it tries to elevate one oppressed group over another, giving no role for those who are in the "oppressor" category. That would be a valid critique if it were true. Rather, liberation theologies acknowledge the power of our social locations and experiences in our understandings of God and the world. They may focus on the experience of one group, but not to the exclusion of other forms of suffering in the world. Oppression is multivalent -- an individual may be oppressed in one sense, and privileged in another.