But nothing draws the rage of the God Scare more than the Bible, which Harris helpfully informs us (the following quotations and assertions are also in Letter to a Christian Nation, passim) "is either the Word of God, or it isn't." This is nice, but it's also almost meaningless, because Harris does not tell us what the Word of God is supposed to be nor how the Bible would qualify as such. Later he appears to offer a definition, saying believers think the Bible is "literal (or inspired)"; this parenthesis mark contains entire wars within its slender arms. Oddly enough, Harris seems to function with an understanding of scripture similar to that of contemporary fundamentalists (who developed the notion of inerrancy in the 1880s; Harris seems to believe that it's pretty much what everybody thought from the moment the author of Revelation put down his pen). That is, he expects the Bible to be a collection of empirically testable propositions and is incredulous when it fails to so live up. For instance, Harris points out that many Christians believe the Bible contains prophecies of the future, but these prophecies are vague. Therefore, God does not exist. The Bible contains lots of stuff that we today would find morally objectionable; therefore, God does not exist. The Bible is an inaccurate source of scientific knowledge. Therefore, God does not exist. Etc., etc.

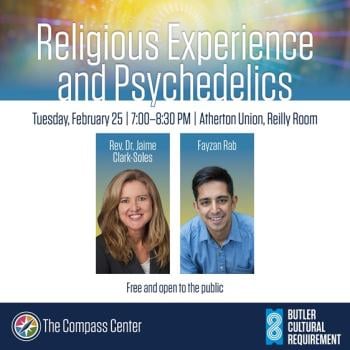

This gets us to the second subcritique of religious methodology leveled by the God Scare: enthusiasm. And here we should talk about the documentary Jesus Camp, which examines a Pentecostal youth summer camp presided over by the pastor Becky Fischer, who is presented as sort of a jolly Joseph Goebbels. Jesus Camp treats us to long extended shots of children weeping, dancing about in ecstasy, and chanting strange things; we're meant to be horrified because enthusiastic experience is self-evidently weird and creepy. This is an old, old complaint, going back to the Protestant Reformation itself: that the subjective, the emotional, the enthusiastic means of gaining truth that mystical religions endorse are freaky and unreliable and tend toward (of course) abdication of reason. Chris Hedges, in his subtly titled American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America, ominously claims of such experiences that "the goal is not simply conversion but recruitment into a political movement" (p. 62). Those who convert do so because of "insecurity"; they are made to feel "inadequacy, self-doubt, guilt, and self loathing" (p. 64). This means, of course, that religion is more or less pathological. For Hedges, all of these emotional, cathartic religious experiences are the products of emotional intimidation by unscrupulous pastors upon fragile congregants who want to create an army of followers.

That diagnosis might remind historians of nothing so much as educated opinion in the mid ‘50s, when folks like the sociologist Daniel Bell and the historian Richard Hofstadter were using thinly veiled Freudian analysis to explain why people would actually choose to vote for Richard Nixon. Being conservative, so the argument went, must actually be a sign of intractable mental tensions; the anomie of modern society, immature nostalgia for a past that never was, etc., etc. -- and, thus, again that charmingly optimistic confidence arises: all rational people will inevitably discard such things, and then we can build Sam Harris's durable future. Today Richard Hofstadter mostly shows up in the introductions of historical monographs to serve as a straw man against whom the author can perform feats of strength, but the suspicion that the arguments religious people make are actually rooted in the fogginess of their overly emotional, insecure, and easily influenced brains still clearly seems plausible to some.

The third critique of religion offered by the God Scare is the tendency to collapse all religion together into the ranks of straw men who think Joshua actually stopped the sun. The most astonishing example here is (the other) noted vampire novelist Anne Rice's journey in and out and in and out of Catholicism. Rice, whose re-conversion to Catholicism garnered some attention back in 1998, has since decided to leave the faith. Maybe. Rice provided three Facebook updates to clarify precisely what she was doing, which included these fascinating lines: "I quit being a Christian. I'm out. I remain committed to Christ as always but not to being ‘Christian’ or to being part of Christianity." In her second post, Rice provides some clarification as to why "Christian" does not mean "committed to Christ." Rather, "Christian" to Rice means anti-gay, anti-feminist, anti-Democratic, and so on; in short, Rice as a believer appears to have been convinced by the God Scare. I certainly don't mean to lump Rice in with Harris, Dawkins, et. al.; I actually think she has a better sense of how religion works than they do, based (confession here) on her fiction as much as anything else. Rather, I offer her as an example of interesting ways in which the God Scare is influencing the ways Americans talk about religion.