The longer you read Catholic history, the more likely you are to find something that will surprise or maybe even beguile you. At least that's been my experience in twenty years of studying Church history. And it just happened again recently when I read The American Catholic Who's Who, an anthology published in 1911. That's where I discovered the fascinating story of a 19th-century artist named Mary Edmonia Lewis.

The longer you read Catholic history, the more likely you are to find something that will surprise or maybe even beguile you. At least that's been my experience in twenty years of studying Church history. And it just happened again recently when I read The American Catholic Who's Who, an anthology published in 1911. That's where I discovered the fascinating story of a 19th-century artist named Mary Edmonia Lewis.

One of the leading sculptors of her time, Lewis was also the first African-American artist to achieve international fame. In 1866, a reporter in Rome wrote:

An interesting novelty has sprung up among us, in the city where all our surroundings are of the olden time. Miss Edmonia Lewis, a lady of color, has taken a studio here, and works as a sculptress in one of the rooms formerly occupied by the great master Canova. She is the only lady of her race in the United States who has thus applied herself to the study and practice of sculptural art.

Over a decade later, an American newspaper declared: "No men hold a position in the world of art equal to this colored artist." Public Opinion praised her for "overcoming the prejudice against her sex and color."

Many details of Lewis' life are vague, but we know she was born about 1845 in upstate New York to a Haitian father and Chippewa mother. Orphaned at ten, she lived with her Chippewa relatives. She discovered her artistic vocation during a childhood trip to Boston, a city famous for its statues. "She went home," the reporter wrote, "to a life purpose that rendered her ears deaf to the taunts of her schoolmates and the cuffs of the village schoolmaster."

A few years later, Edmonia's older brother, a successful entrepreneur, was able to fund her education. In 1859 she entered Oberlin, America's first integrated college, but her experience there was surprisingly negative. Accused of trying to poison two white classmates, she was attacked by a racist mob. After that she moved to Boston to pursue an artistic career.

Her first work to attract attention was a bust of Robert Gould Shaw, a local hero who was killed leading African-American troops (Matthew Broderick played Shaw in the 1989 film, Glory). By 1865, at age 20, she had raised enough money to move to Rome and its well established artists' colony. In a New York Times interview titled "Seeking Equality Abroad," she stated:

I was practically driven to Rome, in order to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color. The land of liberty had no room for a colored sculptor.

In Italy she found a "real republic," where people "left their race prejudices at home." She stayed there for the rest of her life.

Lewis' career intersected with a neoclassical revival in the art world, and she brought a fresh approach to that tradition. Her subject choices reflected her background and interests: Native Americans, African-Americans, biblical figures, and celebrities. When Henry Wadsworth Longfellow visited Rome, Edmonia secretly followed him around the city, sketching a bust of him that Harvard University purchased.

Soon the rich and famous were approaching Lewis with requests for statues, headstones, and even altars. She proved a successful and shrewd businesswoman. In 1873, an American newspaper noted that she earned $100,000 in commissions that year. Her work was in great demand both in America and Europe. Those visiting her studio included President Ulysses S. Grant and Pope Pius IX. About this time, a reporter described her:

Although a fluent talker when the theme is such as to arouse her enthusiasm, she has something of the habitual quietude and stoicism of the Indian race. In person she is rather below the medium stature, and strong and supple rather than delicately made. She bends slightly forward in speaking, pronounces slowly and deliberately, and has a trace of the sadness of both races in her manner, notwithstanding her assured artistic success.

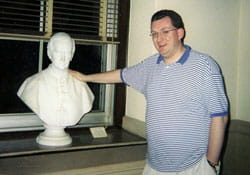

It had long been believed that Lewis converted to Catholicism in Rome, but recent studies confirm she was raised Catholic. Over time, Catholic themes played a larger role in her work. Most of her patrons were affluent Catholics. (Early works include a Madonna carved especially for an African-American parish.) Unfortunately, much of her religious art has not survived, but her bust of Cardinal John McCloskey, the Archbishop of New York from 1864 to 1885, may be found at St. Joseph's Seminary in Yonkers.

Observers frequently described Edmonia as devout. In 1871, she told a reporter: "I have a strong sympathy for all women who have struggled and suffered. For this reason the Virgin Mary is very dear to me." As a Black Catholic artist, she brought a uniquely African perspective to her religious work. One critic, for example, observed that in her sculpture of the Magi, the preeminent figure was the African king, rather than the "Caucasian or the Asiatic."

Observers frequently described Edmonia as devout. In 1871, she told a reporter: "I have a strong sympathy for all women who have struggled and suffered. For this reason the Virgin Mary is very dear to me." As a Black Catholic artist, she brought a uniquely African perspective to her religious work. One critic, for example, observed that in her sculpture of the Magi, the preeminent figure was the African king, rather than the "Caucasian or the Asiatic."