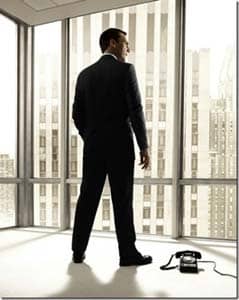

“I know what you want,” Don Draper’s paid escort says to him in the first episode of the fourth season of “Mad Men,” which ended this past Sunday. Sometimes, in the movies, a prostitute is the key to a mysterious man’s heart, but the writers of “Mad Men” have skirted past that cliché. Instead, they have made their hero’s heart impenetrable. For four seasons, we have seen Don Draper (Jon Hamm), a wealthy and successful family man and advertising genius, slalom from mistress to mistress and rise from being the creative director of one ad agency, to a full partner of another. More than that, in this last season, Don is celebrated by admirers as being a sort of artist, a cross between Hemingway and a 1960s art-film director, because of an award-winning ad that he created for a floor polish product called Glo-Coat.

“I know what you want,” Don Draper’s paid escort says to him in the first episode of the fourth season of “Mad Men,” which ended this past Sunday. Sometimes, in the movies, a prostitute is the key to a mysterious man’s heart, but the writers of “Mad Men” have skirted past that cliché. Instead, they have made their hero’s heart impenetrable. For four seasons, we have seen Don Draper (Jon Hamm), a wealthy and successful family man and advertising genius, slalom from mistress to mistress and rise from being the creative director of one ad agency, to a full partner of another. More than that, in this last season, Don is celebrated by admirers as being a sort of artist, a cross between Hemingway and a 1960s art-film director, because of an award-winning ad that he created for a floor polish product called Glo-Coat.

Before season 4 began, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat wrote that “After three seasons of Mad Men, I have absolutely no idea what Don Draper’s intentions are.” At the time, I thought Douthat raised a legitimate question. I kept returning to it in my mind as I watched the fourth season these past few months -- as I watched, that is, the aftermath of Don Draper’s broken marriage, his feeble efforts to connect with his children, and the several business crises which his agency, Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce, suffers throughout its second year of business.

After last Sunday’s season finale, which culminates with Don’s marriage proposal to his young French Canadian secretary, Megan Calvais (Jessica Pare), I made an earnest attempt to resolve Douthat’s question. Here are my answers.

1)If Don Draper wants anything, it is nothing mysterious or unique; it is what any human being wants -- love, shelter, stability, happiness. (“Advertising is based on one thing: Happiness!” he says in the pilot episode of the series.)

2)Don Draper is no longer aware that he is a human being with such wants.

3)His paid escort friend, as worldly-wise as she is portrayed as being on the show, doesn’t really know Don. Not because she doesn’t know what he wants, but because he no longer knows what he wants.

4)Don has become completely swallowed up by the universe of his own advertisements.

The last point is not as outlandish as it might sound. Don has allowed his real problems and desires to become masked by the types of promises that advertising makes -- promises that appeal to your very real human heart and offer you something you can buy, something not very real, and less than true, a product that distracts you instead of fulfilling you. Don is an expert at crafting such advertising, and now he has become his own customer.

Throughout the season, a couple of characters have tried to offer Don something true. Anna Draper (Melinda Page Hamilton), the woman who, more than his real mother, has offered Don something like maternal love, says to Don exactly what he needs to hear: “I know everything about you, and I still love you.”

I know, in other words, all the things that keep you from sleeping at night, and fuel your desire for whiskey -- and I still love you.

Faye Miller (Cara Buono), the market research consultant who becomes Don’s lover midway through the season, offers him not only the affection and stability he needs, but also the truth about what he should do. Don is able to confess his secrets to her, and she returns with calm and with reality: You need to become a normal, real person.

But he rejects it all and becomes a cliché. He marries his secretary, whom he hardly knows apart from a couple of trysts. It is a romance completely unpolluted by good sense. The agency he works for is on the brink of collapse, and it is kept afloat not by his own work, but by that of his younger protégé, Peggy. Anna Draper, by the season finale, has already passed away, and Don abruptly, over the phone, breaks up with Faye. His tethers to the real world have become unhooked.

Don is not an artist, but a dreamer. An artist tells the truth, and Don runs away from the truth.

The main drawback to painting such a comprehensive picture of a brilliant man’s slow process of dehumanization is that he becomes boring. The brilliant advertising pitches that we saw Don present during the first couple of seasons of the show are no longer there. Don now merely repeats himself: his schtick about nostalgia as being the way to the consumer’s wallet feels laughable in the dawn of the cultural upheaval of the 1960s. I have no idea where the writers will take the show next, but if they are planning a happy ending for Don Draper, they will by necessity have to see him suffer through a reawakening from the illusions that Draper has created for himself.

11/2/2010 4:00:00 AM