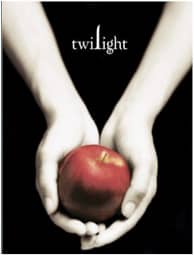

Elaine Heath is the author of numerous articles and books, including the forthcoming The Gospel According to Twilight: Sex, Gender, and God in the World of Stephenie Meyer (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox, 2011) from which this article is partially excerpted.

The books grew into a dark tower on my coffee table, one vampiric novel after another. It was Christmas time, hardly the season of the year to focus on the undead, but I was getting ready to teach a new class on the Gospel in Pop Culture, and I needed to find out why Twilight broke publishing and box office records. Second only to Harry Potter in its worldwide reach, the saga is a romantic adventure about a girl, Bella, who falls in love with a vampire, Edward, and is best friends with a werewolf, Jacob. I was barely a page into the first novel when I realized that there was more going on than just a romance. This was a theological story, too. And it was full of messages about gender. Though the theology intrigued me and the story is compelling, by the middle of the first novel I began to wonder, is Twilight bad news for girls?

The books grew into a dark tower on my coffee table, one vampiric novel after another. It was Christmas time, hardly the season of the year to focus on the undead, but I was getting ready to teach a new class on the Gospel in Pop Culture, and I needed to find out why Twilight broke publishing and box office records. Second only to Harry Potter in its worldwide reach, the saga is a romantic adventure about a girl, Bella, who falls in love with a vampire, Edward, and is best friends with a werewolf, Jacob. I was barely a page into the first novel when I realized that there was more going on than just a romance. This was a theological story, too. And it was full of messages about gender. Though the theology intrigued me and the story is compelling, by the middle of the first novel I began to wonder, is Twilight bad news for girls?

The theme of violence against women runs throughout the Twilight series and is even more pronounced in Stephenie Meyer’s subsequent book The Host. From relatively mild boundary violations to gang rape, most of the women characters in Twilight have been victimized by men. What is most disturbing about Meyer’s treatment of this theme is that it is presented in ways that normalize, even romanticize such violence. Esme, Rosalie, Emily, and Alice have all been victims. Of these, Rosalie’s story is most disturbing with its fallacies about rape.

As Rosalie explains, before she was turned into a vampire she was happily engaged, dreaming of her future as a wife and mother. Then one night her drunken fiancé and his friends found her walking down a dark street. Overcome with desire for her because of her beauty, the men gang raped her and left her for dead. When Carlisle found her, she was about to die, so he changed her into a vampire.

Even as a “resurrected” vampire with more than human perspective, Rosalie believes that the sexual assault that took her life was initiated because of her beauty and desirability (Eclipse, 132). While she exacted vengeance upon her assailants, torturing and murdering them after she was a vampire, she still sees her own body as partial cause for what happened to her.

This is not the message readers need to hear. Rape is a crime of violence, not an act of sexual intimacy. Rape victims are never to blame for the violence of their perpetrators. Rape is never excusable because of a woman’s clothing, beauty, vulnerability, location, speech, or any other aspect of her person. There is never a justification for rape. It is telling that rape is widely used as a weapon in warfare because it utterly humiliates and devastates its victims.

My greatest disappointment with the Twilight series is Stephenie Meyer’s thematic representation of violence against women in a way that minimizes and normalizes abuse. No matter how wonderful it is that Meyer promotes sexual abstinence before marriage, a fact that elicits praise from many religious leaders about the series, she offers a terrible message about violence against women at the hands of their intimate partners. Few of those enamored religious leaders who praise Twilight even notice the saturating theme of violence against women in the novels.

Ironically, part of what makes the messages of violence against women so untenable in these novels is that the reader eventually learns that Edward has some legitimate reasons for part of his abusive and controlling behavior toward Bella. Those reasons all have to do with protecting Bella from real danger. Edward is angry that he can’t read Bella’s thoughts, for example, because he literally can read everyone else’s, a gift that helps him protect those he loves. Edward begins driving her everywhere partly to protect her from the bad vampires and unstable werewolves. He resists physical intimacy with her because he wants to protect her from his own cravings. All of these elements help the reader to “forgive” Edward for his abuse as the story unfolds.

The problem is, abusive men use manipulation, “reasonable” explanations, and other maneuvers including claims to protect and watch over their victims to keep their victims confused and to make victims feel obligated to forgive and endure unacceptable behavior. Readers, who are influenced by what they read, may think that if their boyfriends or spouses are abusive, especially if the abuse is followed by clever explanations and contrition, the right thing to do is forgive and stay together, to kiss and make up. Specialists in domestic violence call this the “honeymoon” stage of the battering cycle. Like all other aspects of the battering cycle, this one helps to perpetrate systemic violence in the relationship.

Is there anything redemptive in Twilight? Or is the series hopelessly flawed by themes of gender violence? There is, in fact, much in these thick, vampiric novels that is good. Reconciliation is the premier gospel theme that binds the story together. A strong and appropriate critique of toxic religion is another subtext of the tale. I just wish that Meyer’s prophetic moments extended to justice for women.

11/18/2010 5:00:00 AM