As we finish our study of the Old Testament and gear up to begin our study of the New, this article on how the King James Bible became the official (though not sole) Bible of the LDS Church took on new relevancy. For appendix, bibliography, references, and footnotes, consult the original article in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Vol. 22:2 (Summer 1986): 19-41. We thank Dialogue for our continuing partnership.

As we finish our study of the Old Testament and gear up to begin our study of the New, this article on how the King James Bible became the official (though not sole) Bible of the LDS Church took on new relevancy. For appendix, bibliography, references, and footnotes, consult the original article in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Vol. 22:2 (Summer 1986): 19-41. We thank Dialogue for our continuing partnership.

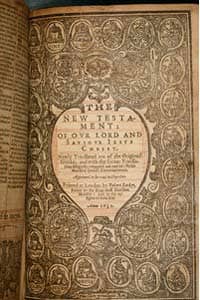

The excellence of the King James Version of the Bible does not need fresh documentation. No competent modern reader would question its literary excellence or its historical stature. Yet compared to several newer translations, the KJV suffocates scriptural understanding. This essay offers a historical perspective on how the LDS Church became so attached to a 17th-century translation of the ancient biblical texts.

To gain this perspective, we must distinguish between the sincere justifications offered by leaders and teachers in recent decades and the several historical factors that, between 1867 and 1979, transformed the KJV from the common into the official Mormon Bible. In addition to a natural love of the beauty and familiarity of KJV language, these factors include the 1867 publication of Joseph Smith's biblical revision, the 19th-century Protestant-Catholic conflict over governmental authorization of a single version for use in American public schools, the menace of higher criticism, the advent of new translations perceived as doctrinally dangerous, a modern popular misunderstanding of the nature of Joseph Smith's recorded revelations, and the 1979 publication of the LDS edition of the Bible. While examining these influences, I give special notice to J. Reuben Clark, who by 1956 had appropriated most previous arguments and in the process made virtually all subsequent Mormon spokespersons dependent on his logic. So influential was his work that it too must be considered a crucial factor in the evolving LDS apologetic for the King James Version.

The Common Inherited Version

When the Geneva Bible was published in 1560, it made no attempt to disguise its Protestant origins: its prefatory dedication to Queen Elizabeth expressed the optimistic hope that her majesty would see all papists put to the sword in timely fashion. The Geneva Bible's marginal notes contributed greatly to its popularity among the Protestant laity, but royalty, clergy, and Roman Catholics were disturbed by many of the notes' interpretations. The pope naturally objected to being identified as "the angel of the bottomless pit" (Rev. 9:11), and defenders of royal privilege were equally upset by a note on Exodus 1:19 approving of the midwives' lying to Pharaoh. It was thus no great shock when England's new king, James I, commissioned a fresh translation in 1604.

When the new product first issued from the press seven years later, not all readers were favorably impressed. Some thought its English barbarous. Others criticized the translators' scholarship. Prominent churchmen, like the Hebraist Hugh Broughton, "had rather be rent in pieces by wild horses, than any such translation by my consent should be urged upon poor churches." However, the revision -- for it was a revision of earlier versions -- was well received by the authorities and therefore authorized, though never formally, to be read in the churches. But for two generations this Authorized Bible waged a struggle to replace the Geneva translation in popular usage. The Puritans brought this struggle to America, where the conceptions and arguments of the two factions in the famous "Antinomian Controversy" in Massachusetts (1637) were conditioned by the respective use of the two different Bibles.

Gradually, the phraseology of the Authorized Version came to be viewed as classically beautiful, and it wielded a major influence on English literature and the language itself. So completely did its turns of phrase eventually capture the popular mind that by the 18th century many Protestants felt it blasphemous to change it or even to point out the inadequacies of its scholarship. The subsequent efforts of Noah Webster and others to mend its defects had little effect on most antebellum Americans. Joseph Smith's generation was raised on the King James Version (as it came to be known in this country) as thoroughly as it was raised on food and water.

Yet while the familiar translation influenced virtually every aspect of his thought, Joseph Smith was in no sense bound to it as an "official" Bible. To the contrary, he regarded the version he inherited as malleable and open to creative prophetic adaptation. He believed the Bible was the word of God, but only "as far as it is translated correctly." And, he noted, the King James Version was not translated correctly in thousands of instances. The Prophet used the KJV as a baseline because it was generally available and known, but the thrust of his work was to break away from the confinement of set forms, to experiment with new verbal and theological constructions while pursuing his religious vision. Through good honest study, he worked to understand Hebrew and other tongues that would improve his scriptural perspective. While so doing, he experimented freely with Bibles in various languages, once observing that the German Bible (presumably Luther's) was the most correct of any.