I found Adam McHugh's reflections on Advent very interesting, largely because they are in many ways the opposite of mine. Advent was never a time of stress, rush, or noise for me. In fact, I love Advent and rejoice in it because it seems like an annual "reset": a pause in the tumbling rush of time to refresh, recharge, and remember.

The experiences of our earliest years stay with us for a lifetime. Where Adam McHugh felt alienated by a busy Advent that seemed to be the province of extroverts, I felt a sense of quiescent participation in a timeless ritual bigger than myself. Advent, unlike most other things in life, was not a weight on my shoulders. It had a magic that did not depend on me.

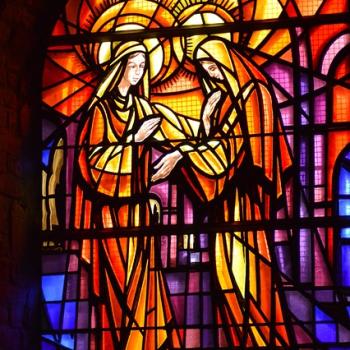

We are, in our generations, the guests of Advent: we visit it during our time on earth, and bring away from it our separate memories. Mine are of candlelight, Advent wreaths, brothers and sisters, mother and father, cold starry nights, frost on windowpanes, soaring choirs and Advent hymns, organs and trumpets, and people in coats and boots greeting each other in garland-draped vestibules with hugs, handshakes, and smiles. The Christmas story, the idea of a hush falling over the earth, of the very stars colluding to announce the coming of the promised one, and of all creation, seen and unseen, known and unknown, waiting expectantly for the birth of one small boy -- these wonders never grow old, and Advent is our appointed time to remember and savor them.

For me, Advent is integral to memories of family and childhood. We observed Advent as a family by lighting the candles on our wreath at dinner each evening, singing hymns, and reading the passages of scripture indicated by the old Episcopal prayer book. Decorating the wreath at the beginning of Advent was the children's task. We children rotated the scripture readings at the dinner table. We learned to read music as vocalists, and to sing in parts, largely from Dad's direction in our family Advent ceremonies. The old Hymnal 1940 was our companion and guide.

The 1960s and 1970s raged around my childhood, but in the landscape of my memory some of the most prominent features are the balance and inner quiet of ritual and tradition. Advent was a big part of that. It represented the continuous run of peaceful specialness between Thanksgiving -- long my mother's favorite holiday -- and Christmas Day. It had sights, sounds, smells, ceremonies, and silences all its own.

And the silences were important. They paced the season and anchored it. One of the best-loved lines of scripture is from Luke's account of the Christmas story: Luke 2:19, which says that Mary "treasured up all these things and pondered them in her heart." I have always associated this treasuring and pondering with the season of Advent. When I was a small child the pondering didn't last long; it took place when I lay for a moment next to the Christmas tree, looking for my reflection in the ornaments. Growing older, I would do my treasuring and pondering in the quiet time after finishing a semester exam, or sitting dispiritedly before a football game when things weren't going my team's way. (Football, I should mention, was a really fun part of Advent. I am, after all, from Oklahoma.)

The treasuring and pondering have gone with me through time and across continents, from being at sea during Advent to being stationed overseas, and from standing watch and worrying about Soviet ballistic-missile submarines to manning the office alone on an Advent afternoon, wrestling with personnel problems and fleet readiness issues. The sense has remained with me that problems and situations come and go, but the treasuring and pondering -- affirmed with ceremony in a season of their own -- outlast them.

Stately beauty was a key feature of the Advent of my childhood. I don't know that I would have the same memories of it without the liturgical solemnity and traditional music. Those elements speak an inner quiet to me that I don't find in contemporary forms of worship. (Which, just to be clear, is not an indictment of contemporary worship.) But that ready-made connection to the generations who have celebrated Advent before us isn't the source of the season's defining significance for me. Nor is that source the connection of Advent with childhood and family, important as those are.

It is this year's Advent, in fact, which has crystallized the season's greatest meaning for me. Many adults in 2010 have a sense of impending crises and looming decisions for mankind, burdens of political and social turmoil for which our shoulders simply aren't broad enough. This apprehension of the responsible generations is the opposite of the childlike freedom from concern that enhances the magical wonder of Advent and Christmas.

But the Christmas story itself has the answer -- and the prelude of Advent is essential. It reminds us that there were prophecies and wars and destruction, and centuries of yearning and doubt, before the prophecies were fulfilled in the life of a humble family. Into that little family, subjects of an indifferent pagan empire, the child of promise was introduced as a helpless baby. God didn't send a powerful, broad-shouldered warrior or a great political leader. His purposes are not constrained by our limitations.

Advent reminds us of this. It reminds us that neither Christmas nor Easter is the end of the liturgical year: the longest stretch of the church calendar falls after Pentecost, the period in which our thoughts turn to our life and work as the church of today. We can relax during Advent. We can enjoy the ceremony, the beauty, the treasuring and pondering. We can look forward to things with the trust of little children. Because Advent reminds us of the most important things of all: it isn't all up to us -- and we know how the story turns out.

12/13/2010 5:00:00 AM